Edith Hampton is in urgent need of food to feed her children.

That’s what brought her out on a cloudy Wednesday morning to Mackenzie Elementary-Middle School in the Detroit district. It was the first day of a massive effort to ensure students don’t go hungry during the statewide schools shutdown that officials hope will slow the spread of the new coronavirus.

“If I don’t eat, I don’t care. As long as my kids eat. Yes, that’s all I care about,” Hampton said.

In Detroit, where child poverty rates are high and a majority of students qualify for subsidized school meals, the COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to worsen the inequities Detroit families living in poverty face. Many students in the city rely on school for breakfast and lunch, and many district and charter schools, as well as community agencies, are stepping up to provide meals. There are about 51,000 students in the district, and close to 86 percent are economically disadvantaged.

Hampton hadn’t been going to her job as a caregiver because she was afraid of contracting the coronavirus and spreading it to her family. Money is drying up, and the grocery store shelves near her home are bare.

On Wednesday, she was among a steady stream of people picking up meals at the school, one of 58 in the district distributing food. Nearly 26,000 Detroit families were fed across the city, according to Detroit district superintendent Nikolai Vitti.

The meals are available for anyone who stops by, even if their children don’t attend district schools. Hampton’s children attend a private school.

For a map of the locations of meals provided by the Detroit district, charter schools and community agencies, go here

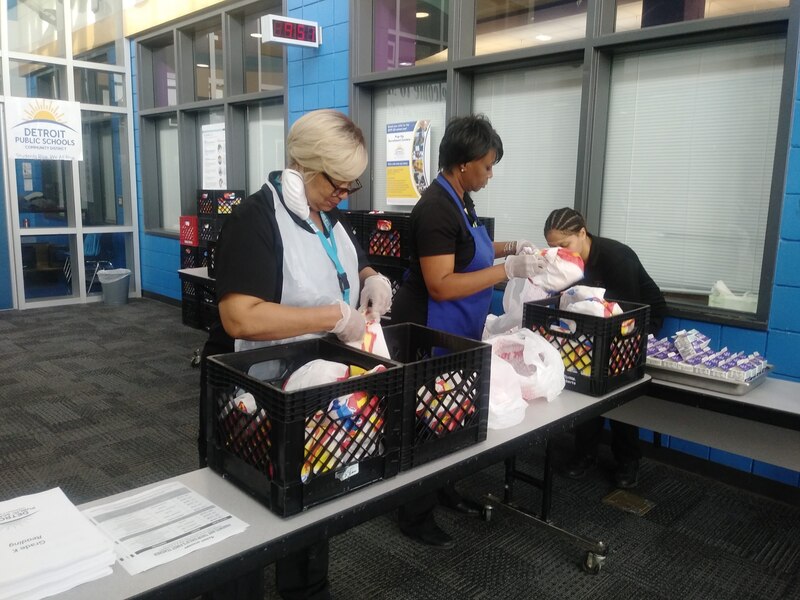

The day started off slow, with just a few cars arriving, but the pace quickened after about an hour. It was organized like a drive-through, with school staff greeting drivers, distributing food, and handing out academic packets.

The cafeteria workers inside the school — all of them wearing gloves and some wearing face masks — had been up since early morning preparing 800 breakfasts and lunches.

Vitti spent the morning visiting the food distribution centers. He said he was proud to see district employees stepping up to the plate.

“Everyone is all hands on deck and trying to make this work for people who need it,” Vitti said. “We’re trying to keep all 58 sites open as much as possible because we know there’s a need in the community.”

It’s been a challenging time for the Detroit district. Vitti’s Saturday announcement that an Osborn High School staff member tested positive for the coronavirus has shaken the school community.

During a Tuesday night school board meeting, he expressed concern that the staff needed to distribute the meals would stay home because of fears over the virus. Each school needs at least four staff members to ensure the food distributions run smoothly, he said. If too many employees stay home, the number of available sites could drop.

If there is a staffing gap, Vitti said the district is considering recruiting volunteers.

The state has ordered schools shut down through April 5, but there are widespread fears that the shutdown could last longer. If that happens, the need to feed children will become even more critical.

“Over time, this distribution process will become more important as food becomes more scarce and people find it more difficult to go to the grocery stores and have enough income to pay for food,” Vitti said this morning at the school.

If that happens, Hampton will rely on relatives.

“They’re not going to let me starve. And they’re definitely not going to let my kids starve,” she said.

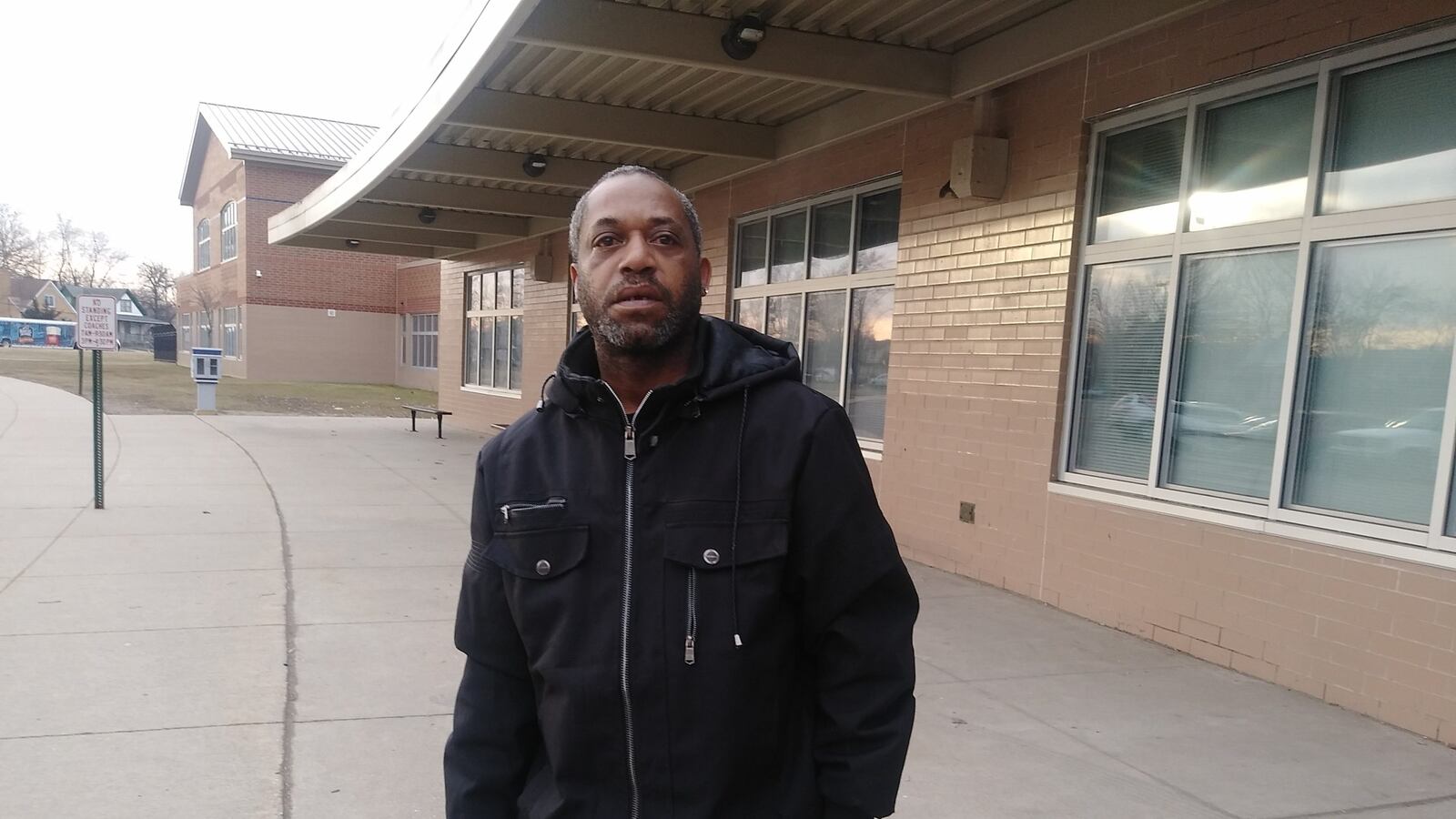

Warren Cunningham, a father of two students who attend Mackenzie, was on his way to pick up an unemployment form when he stopped at the school. He got six meals for his three kids, two who attend Mackenzie and one who attends a private school.

Money is tight for Cunningham. He was laid off from a job as a cook at a coney island soon after Gov. Gretchen Whitmer ordered restaurants to close to dine-in customers at 3 p.m. daily. He said he’s got a stocked fridge, but every extra meal he can get is a big help.

He’s frustrated right now because he can’t be the provider that he needs to be.

“Right now it sucks. It really sucks. How am I going to pay bills if I’m stuck in the house?” he said.

Lanora Jordan, a mother of five children ranging in ages from 5 to 14, relied on the school system to make sure her kids wouldn’t go hungry.

“A lot of people are counting on that Detroit Public School food,” she said.

Jordan was a janitor in a nearby school district, but the shutdown means she’s no longer receiving a paycheck. Unemployment, she said, likely won’t provide enough to take care of her family.

She spent the morning scouring the internet to find places that are giving food away. She is planning to go to a local bar Saturday to get more meals.

“Every day. I’m going to keep coming and getting meals,” she said.