The principal at Hutchinson Elementary School in Detroit all but begged Karen Lemmons to become a librarian.

The year was 1996, and the district employed 139 librarians. Lemmons taught students how to navigate 10-pound encyclopedias and card catalogs.

Twenty-four year later, those aspects of her job have largely disappeared: She spends more time teaching kids how to find reliable information online than helping them pick books off shelves.

Her job has changed — in fact, it has just about disappeared.

She is one of just two full-time certified librarians still employed by the Detroit Public Schools Community District, the state’s largest school system with roughly 100 schools and 50,000 students.

Her story shows how once-ubiquitous school librarians all but disappeared in Michigan, and it helps reveal the costs of their disappearance.

To be sure, filling the state’s school libraries would be an uphill battle, even assuming that advocates got the necessary Republican backing for the idea. There is no statewide listing of school libraries, making it impossible to tell how many librarian slots need to be filled. And after decades of job reductions, there are serious doubts that schools would be able to find enough librarians right away, despite innovative new efforts to help more teachers get certified as media specialists.

Lemmons argues that by helping kids develop a love of reading, librarians can be just as effective as the state’s new “read or flunk” law for third-graders in improving the state’s stagnant reading scores.

“You’re telling me that you’re going to have a third-grade reading law, and you’re going to have reading assessments, and nowhere in this K-8 education landscape is there a librarian saying, ‘Hey, this student just might want to pick up this book and read,’” she said. “I’m a little confused.”

When she started at Hutchinson, the library was small and full of outdated books. Lemmons set about bringing it up to speed. She visited library conferences, bringing home suitcases full of books she thought her students would enjoy.

In meetings with publishers, she demanded that they give her stories that would resonate with her mostly African-American students.

“They responded positively because I was coming straight at them, like, ‘our children need to see ourselves in these stories,’” she said.

Two decades later, she is still at it, attending conferences and buying books on her own dime.

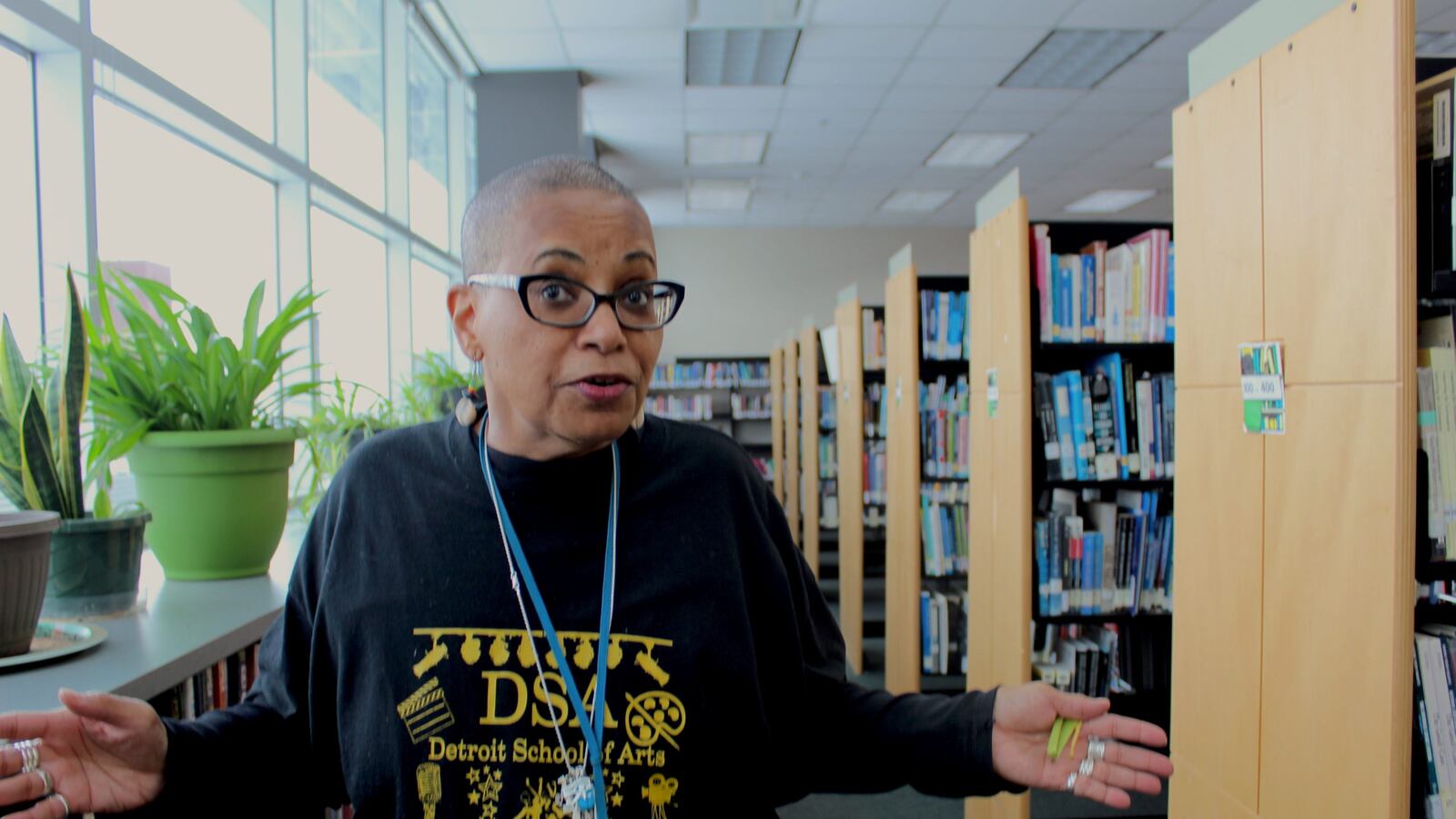

Teachers at her current school, Detroit School of Arts, still rely on her to help them find materials to use in class. At her suggestion, a social studies teacher at the school recently began using “We Are Not Yet Equal,” a book published in 2018, to teach lessons about race in America.

Few teachers in Michigan can expect the same kind of help. Over the last 20 years, the number of school librarians statewide plummeted until just 8% of schools had one. The downward trend was driven by new technologies, which fueled the perception that librarians’ skill sets were outdated. Stagnant school funding and the 2007 economic downturn didn’t help.

School districts with fewer resources were the hardest hit. Librarian posts in Detroit disappeared especially rapidly as the city district verged on bankruptcy and state officials took control, closing dozens of schools in an effort to combat declining enrollment.

“It hit me, if we have these school consolidations, not only are teachers going to lose their jobs, but librarians are going to lose their jobs as well,” Lemmons said.

Like just about everyone in Michigan over the age of 30, Lemmons was a student at a time when school librarians were the norm. Growing up in Detroit, she attended now-shuttered Pattengill Elementary on the west side, where Ms. Redd presided over the library with fiercely precise diction.

“She would say, ‘there is no talking’ — and you would hear that ING — ‘in the library.’ I always remember how she enunciated so properly.”

Lemmons style is less strict: She offers students hugs and a listening ear, and she allows them to read and hang out in the library during lunch. “I may not be able to offer any advice, but I will listen,” she said.

Her job is different, too. Though she’s listed as a full-time librarian, Lemmons has increasingly filled other roles around the school. She coaches the robotics team, keeps up the school’s Facebook page, and teaches three classes — information science, journalism, and SAT prep.

While she was initially reluctant to take on responsibilities that seemed to fall outside her expertise, Lemmons says she understands that the district needs all hands on deck.

“I understood,” she said of being asked to teach SAT prep. “We have to work on those SAT scores.”

The Detroit district’s plans for boosting reading scores don’t include librarians, said Chrystal Wilson, a district spokeswoman, in a statement. She pointed out that the district has overhauled curriculums, helped build up classroom libraries, and taken steps to improve teacher retention.

“The need for certified librarians declined due to a variety of reasons, the emergence of technology and media centers, budget cuts and the shortage of individuals who met the state certification requirements for the position,” Wilson said. “Students are exposed to books every day in class.”

Lemmons’ library at Detroit School of Arts belies the dire state of her profession. Perched on the sixth floor with tall windows on three sides, it gives students a panoramic view of the city.

Library advocates argue that her work should be a priority in a state where just 44% of students passed last year’s state English exam.

“The data is very clear,” said Darrin Camilleri, a Democratic state representative. “Schools with school librarians do better than those that don’t.”

The disappearance of librarians is “obviously unacceptable,” he added. “Students, particularly in our highest-need communities, are lacking resources to help them achieve the American dream. Literacy helps them be successful students and have successful careers. It helps them be good citizens and understand our complex world.”

A group of state legislators, including Camilleri, is mounting an effort to require that schools reinstate librarians.

It is not going well. Months after the package of bills was filed, there is no hearing scheduled amid resistance from leaders of the GOP-controlled legislature to the potential costs of the policy.

“I’ve never heard anyone say that they don’t believe in school libraries, but they always come back to well, we don’t have the money,” said Kathy Lester, advocacy chair of the Michigan Association for Media in Education.

It’s hard to pinpoint the cost of reinstating librarians across the state. Budget analysts for the legislature won’t release an official cost report unless the bills receive a formal hearing, and even then, nailing down a price tag would be tough.

Without a major change to the funding system, there’s little hope that the Detroit district will be able to hire more librarians, Superintendent Nikolai Vitti said in an interview last November.

“I would agree that there is a need to reestablish our libraries,” he said, adding “but we need to keep on investing in teacher salaries.”

While Lemmons’ role has changed drastically over her 24-year career, she is unwilling to give up her role.

“I tell administrators, ‘you won’t ever see me shelving books,’’’ she said, noting that she spends time after school and during the summer cataloguing books, shelving, and updating the collection. “Because they say, ‘Oh, we can get a volunteer to do that.’”

“I want them to see me as an instructional partner. I want them to see someone who can get students to read recreationally.”