Two weeks into the school year, Monique Snyder had to tell a dozen working parents that they would have to find somewhere else for their children to learn online.

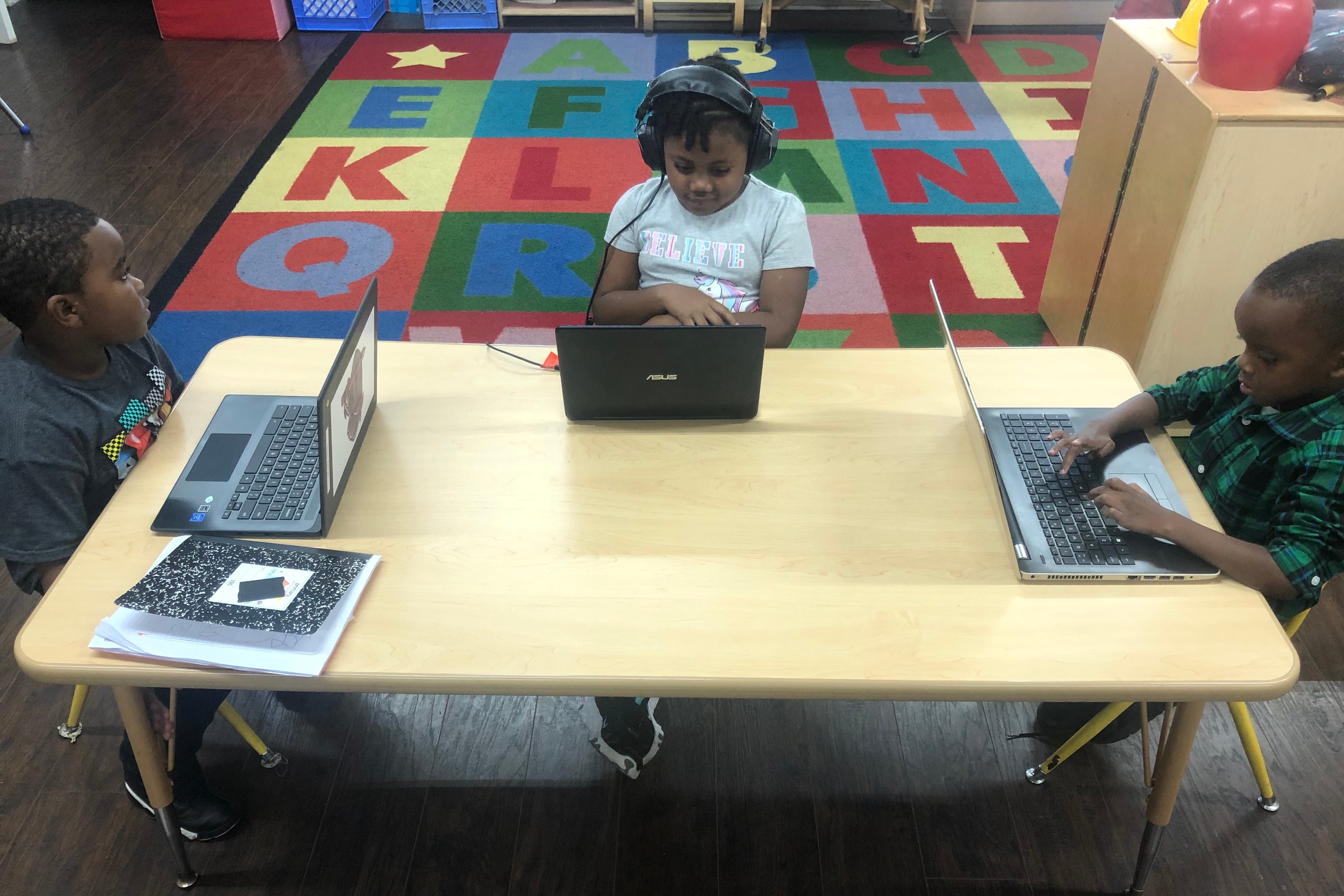

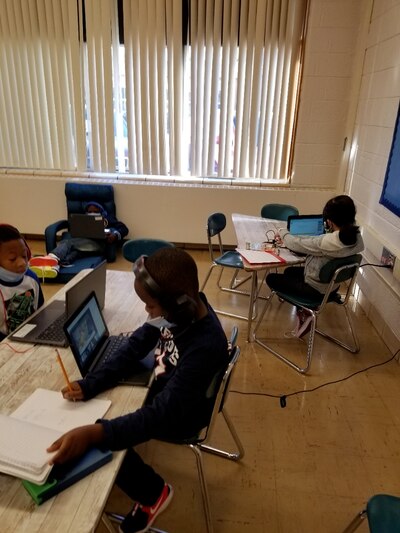

Like many child care providers in the Detroit area, Snyder has opened her centers to young K-12 students whose classrooms remained closed due to the coronavirus pandemic. But Snyder learned this month that the state won’t subsidize care during the school day for children from low-income families.

She told desperate parents that they would have to pay her out of pocket or find another place for their children to learn.

“It was horrible,” said Snyder, whose business is already in danger of closing due to the pandemic. “The biggest question they kept asking me was, ‘What am I supposed to do?’ And I literally did not have an answer.”

The coronavirus child care crunch is falling hardest on low-income families of color, many of whom work in-person jobs in sanitation, grocery, and health care that the state has defined as “essential.” When these families have young students learning online — something that is more likely in Black communities, according to a recent Chalkbeat/AP analysis — many parents find that they have no safe place to send their children during the work day.

“Just imagine the one mom who has to leave the 8-year-old in charge of the 5-year-old and the 3-year-old,” Snyder said. “That’s where my head is, as a parent.”

There’s been no reliable solution to this problem in Michigan, where a patchwork of local agencies have been left to make key decisions about reopening schools and coordinating child care. Some school districts across the state offer free space and support for children learning online, while others charge for child care during the school day or don’t offer any at all.

The same issue is playing out nationwide. In cities where virtual learning is prevalent, kindergarten enrollment is down as low-income families opt to keep their children in in-person preschool programs during the work day.

Many parents in the Detroit area jumped at the chance to drop their children off with their nearby child care provider during the school day, only to be told by providers in the second week of school that the state wouldn’t cover their tuition.

Christina Waller’s 7-year-old son attends a charter school in Detroit, and he will spend the fall learning online. He first attended Snyder’s center, Brainiacs Clubhouse, when he was 2. Waller was relieved when she learned that she’d be able to drop him there while she worked as a clerk at Henry Ford Hospital.

Waller is the family’s sole breadwinner. Her income is low enough to qualify him for child care subsidies, and she anticipated that the state would mostly pay for his care. Then Snyder told her that the state wasn’t paying subsidies for school-aged kids — Waller would have to pay $500 a month if she wanted to continue dropping him off while she worked. Waller says she contemplated quitting her job, but ultimately decided she had no choice but to stretch her budget and pay her son’s tuition.

“I can’t afford it, but [not paying] is really not an option,” she said, noting that she was effectively paying out-of-pocket so her son can get a public third-grade education: “I never thought I was going to be paying for public school.”

Other parents had no choice at all — they had to pull their children. Snyder was supporting 17 school-aged kids with virtual learning when she learned from a child care official that the state wouldn’t pay their tuition. After she told parents they’d have to pay, only five of them returned.

State officials say there isn’t enough money in the child care subsidy program to pay for school-aged children. In a typical year, the subsidies provide free or reduced-price care to about 34,000 kids, making it one of the largest child care programs in the state.

The Michigan Department of Education “is aware of the need to support school-age children and providers caring for those children during virtual schooling,” said William DiSessa, a department spokesman, in an email. “However, we need additional funding” to pay providers.

The issue is being discussed as part of upcoming budget negotiations, DiSessa added.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment, nor did the office of Shane Hernandez, the Republican chair of the House appropriations committee.

“Somebody needs to figure this out,” said Denise Smith, implementation director of Hope Starts Here, a child care initiative in Detroit. “The early childhood programs are propping up the system in this way, and they’re not being compensated to do it.”

In addition to helping parents, paying providers to care for school-aged kids would provide a badly needed infusion of cash to a child care system on the brink of collapse. In Detroit, one of the largest child care deserts in the country, many providers say their businesses could soon fold as enrollment craters due to the pandemic and federal aid dries up.

This spring, with the help of federal money, the state reimbursed child care providers who cared for school-aged students from low-income families. Memos sent out by the state this summer said that providers would not be allowed to continue billing for these students this fall, but not every provider was aware of the change.

“We’re keeping the children safe,” said Jenice Lomax, owner of Child Star Development Center in Detroit. “We’re keeping an eye on them. We’re helping them out. Why wouldn’t we get paid?”

For many families, child care centers are the only option for keeping their children safe. While some school districts, such as the Detroit Public Schools Community District, provide learning spaces for children whose parents have to work in person, many don’t. Others, like Grosse Pointe Public Schools, charge for child care.

Most of the five elementary-aged students at Lomax’s center attend MacDowell Preparatory Academy, a nearby charter school that opted for fully online learning this fall but doesn’t offer students a space to learn while their parents are at work.

Princess Bradley’s three children also attend a charter school that isn’t opening its doors to virtual learners. For the first weeks of school, Bradley sent the children — ages 6, 7, and 12 — to Snyder’s child care center. But when she picked them up Wednesday, Snyder told her that the state wouldn’t subsidize her children’s care.

Bradley, the sole breadwinner in her house, can’t afford to pay the $1,500 a month she’d need to continue bringing her children to the center.

“That’s rent,” she said.

Since then, Bradley has taken three days off from her job as a bookkeeper for a nonprofit in Detroit to care for her kids. They also spent one day with her mother and one day with her sister, but Bradley thinks she’ll probably have to reduce her work hours.

“I’m digging into my savings,” she said. “I’ve been trying to find different types of funding to pay for them to go to daycare, but I haven’t found anything.”