KIPP, the largest nonprofit charter school network in the U.S., plans to open a school in Detroit. If the school can replicate KIPP’s national track record of academic success, it would immediately be one of the highest-performing in the city.

For years, some education advocates in Detroit have tried to attract KIPP and other organizations like it, but the city’s fiercely competitive, open-market model of schooling and Michigan’s school funding model got in the way.

Now, with the help of an anonymous $20 million donation toward a new KIPP campus on the city’s east side, those advocates hope that the 25-year-old network will give more Detroit students a shot at attending a high-performing school.

“It’s terrific news,” said Lou Glazer, president of Michigan Future, an education think tank that has funded charter schools in Detroit. “KIPP is one of the better national operators. People have been trying to get them here for 20 years.”

Whether KIPP can do more for Detroit children than other schools have done remains to be seen. Its new school, KIPP Detroit: Imani Academy, will open in fall of 2021 or 2022 as a 110-student kindergarten program, with plans to expand to a 1,300-student K-12 school at a rate of one or two grades per year.

That means it will likely be four years before KIPP students take standardized exams, which could measure comparable achievement, in Michigan.

Still, KIPP will stand out immediately in Detroit.

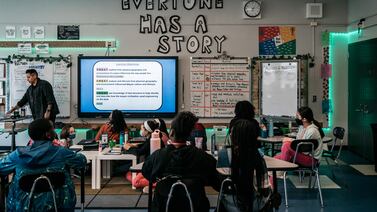

The city is home to dozens of mostly small, locally run charter schools that consistently perform below state averages by virtually every academic measure.

KIPP enrolls more than 100,000 students in 20 states, and has a track record of producing strong academic outcomes in low-income communities of color (almost all of its students nationally are low-income and Black or Latino). The organization is continuing to expand with the help of tens of millions of dollars in federal charter school grants.

Detroit is known for fierce competition between schools for students and funding. KIPP is known for sharing its practices with neighboring school districts.

What’s more, KIPP will have a substantial funding advantage: a $20 million campus plus millions of dollars from the national KIPP organization and federal charter school grants. Many schools in economically depressed areas like Detroit struggle to maintain school buildings, and charter schools don’t receive any dedicated funding for facilities.

Candace Rogers, the superintendent of the new school, said KIPP hopes to continue its practice of collaborating with other education groups. Rogers was previously principal of Detroit Enterprise Academy, a Detroit charter, and has worked with KIPP’s national organization for roughly a decade.

“We look forward to long, productive partnerships in Detroit,” she said in an email, adding that KIPP would also continue its practice of supporting its students until they complete their higher education. KIPP counsels students and their families about applying to college, partners with colleges that provide resources for first-generation college students, and follows up with students throughout college.

“We make a two-decade commitment to our students’ educational journey: beginning in kindergarten and continuing for a decade after eighth grade (to and through college),” Rogers said.

New charter schools in Detroit often encounter skepticism from local school and community leaders who point out that the city already has too many schools, and that adding more fosters competition for funding that hurts students.

“I do not believe the city needs another charter school,” Nikolai Vitti, superintendent of the Detroit Public Schools Community District, said in a statement. “Instead, energy, resources, and time should be spent on the schools (public and charter) we already have. In addition, there are plenty of ‘model schools’ in our district (and even a few charters) that are examples of higher performance. No one needs KIPP to demonstrate what our students can do with the right leadership, teachers, and systems and processes. We know what this looks like.”

Skepticism will not surprise KIPP officials, especially as leaders of the national Democratic Party take a more critical stance toward charters. School boards in other states have rebuffed new KIPP schools in recent years.

Jack Elsey, executive director of the Detroit Children’s Fund, a nonprofit that recruited KIPP to Detroit, agreed that there is an oversupply of classroom seats in Detroit. “But the more important question is, ‘how many quality schools do we have?’” he asked.

“And the answer to that is: not nearly enough. In fact, the vast majority of schools in Detroit do not perform well. We can discuss all the reasons for why that is the case, but when you have a chance to bring in an organization with a proven track record of academic success like KIPP, you seize it.”

Unlike in many other major U.S. cities, the local school board in Detroit does not have a say in which charter schools open where. KIPP’s charter was approved in December by Central Michigan University, a public university two hours away from Detroit that is one of numerous charter school authorizers empowered to open charter schools in the city.

KIPP has faced criticism as one of the charter organizations that built strong academic results in part through strict “no excuses” discipline policies, which some critics view as implicitly racist. Vitti said he believes “Detroiters will raise questions” about KIPPs “history with student discipline and their approach.”

KIPP and some other charter networks have since relaxed their approach somewhat. “We don’t pretend to have all the answers, but one of the great things about KIPP is we are a learning organization working hard to evolve,” Rogers said.

The national KIPP organization will shape most aspects of the school, including curriculum, teacher training, and discipline policies.

Still, an appointed school board will make key decisions about direction. Elsey said the school and school board would have “local, Detroit leadership.”

Some key details about the project — including where the school will be housed — remain fuzzy. KIPP’s application for a charter specifies an initial temporary address of 11457 Shoemaker Street, a warehouse complex on the city’s far east side that currently houses an early learning program. Backers say they haven’t yet settled on the site, or on the future site of the new K-12 campus.

In addition to standard public school funding from the state, the new school will also receive $2 million from the national KIPP organization, $3 million in federal charter school start-up grants, and $1 million from private fundraising, according to the application.

Charters with substantial philanthropic backing are not a new phenomenon in Detroit. One of the city’s largest charter networks, University Prep Schools, draws heavily from a Michigan philanthropy. The network typically performs better than the city average, but its test scores do not approach state averages.

Detroit education advocates who have been trying for years to attract national education organizations to the city welcomed KIPP’s announcement.

“KIPP has demonstrated their ability to deliver quality education opportunities for students for years,” Elsey said. “Their arrival to Detroit means that now, more children in our city will have an opportunity to receive an excellent education.”

Some speculate that national organizations stayed away from Detroit for many of the same reasons that schools here already struggle: anemic state funding, an oversupply of schools, and a wide-open school market with few quality controls.

“There was so much movement between schools and hyper competition, it actually undermined the idea of quality, because people were going to the highest bidder,” said Robin Lake, director of the Center for Reinventing Public Education, an education think tank, who has conducted research in Detroit. “And sometimes literally: ‘Who can offer me a laptop?’ School quality just wasn’t part of the discussion.”

Lake said KIPP’s arrival could galvanize the city’s schools.

“KIPP can show what’s possible,” she said. “They don’t work miracles. They don’t overcome decades of poverty in one swipe. But they can create powerful outcomes. It’s a proof point.”

It won’t be easy. Detroit public schools struggle from longstanding structural problems such as the relentless churn of teachers and students among schools.

“Teacher turnover rates [at KIPP] have been historically very high,” said Chris Torres, a professor at Michigan State University who worked as a consultant for KIPP and has become a critic of some of the network’s practices.

“They tend to recruit less experienced teachers who are willing to abide by the KIPP model, which given Michigan’s context could be something to pay attention to. There’s already a very low supply of teachers, especially younger, newer teachers.”