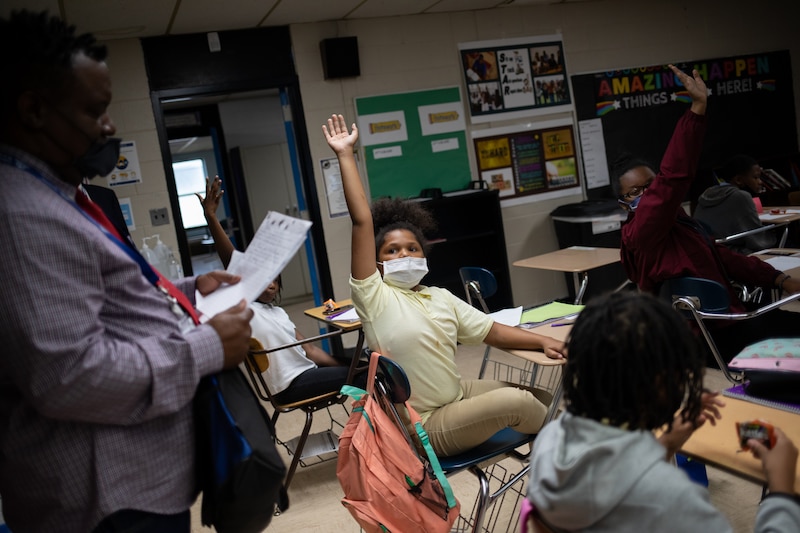

The inspirational words were written with large letters and taped to the tops of the light wood desks, a fitting backdrop for an activity that had new teacher Will Cannon connecting with a group of sixth graders he was meeting for the first time.

“You are a champion,” said one of the cards. “Triumph,” “Fabulous,” “Conquer,” and “Passionate,” said others.

“Tell me what that word on your desk means to you,” asked Cannon, who had taped the cards to the desks hoping they would inspire his students.

“A lot,” called back one girl, whose desk displayed the phrase “You are amazing.”

Cannon is among 55 people who entered classrooms in the Detroit Public Schools Community District for the first time this school year through a new program — the first of its kind in Michigan — that trains them during a summer academy tailored to the particular challenges of teaching in Detroit.

This program, called the On the Rise Academy, represents the first time a district has developed its own alternative teacher certification program, which the Michigan Department of Education approved in January. And in May, the department approved a second certification program for New Paradigm for Education, which manages the Detroit Edison Public School Academy network of charter schools.

Around the nation, alternative programs operating outside higher education institutions are growing as districts like Detroit seek to train their own, more diverse, workforce. School districts in cities such as Boston and Dallas already operate similar programs. Indiana lawmakers are weighing whether to allow districts to certify their own teachers to ease shortages.

In the Detroit district, about three-quarters of the fellows, as they’re called, previously worked in support positions such as paraprofessionals, attendance agents, and academic interventionists.

Superintendent Nikolai Vitti said during a recent school board meeting that the district decided to apply to run its own program because there are talented people in those positions who need an opportunity to put them on a path toward certification. The district is planning to launch another component of the academy next year, this one focused on current teachers who want to become recertified in an area of critical need, such as math and science.

“It makes complete sense to develop your own … because those employees know our students,” Vitti said.

The aspiring teachers — who must have bachelor’s degrees and pass the Michigan Test for Teacher Certification — undergo a hiring process that includes conducting a sample lesson before interviewers and taking feedback on that lesson, then conducting the lesson again.

Once selected, fellows are required to attend a six-week summer institute. There is coursework, but a key part is teaching summer school supervised by a high-performing teacher. Those who make it through the summer institute receive an initial teaching certificate before entering classrooms full time. They earn the same $51,000 salary as beginning teachers in the district.

The fellows receive individual and group coaching throughout the school year. They also are required to take more coursework in addition to teaching full time. Tuition is $6,000 but is waived if fellows teach in the district for six years. Fellows are required to teach in the district for three years.

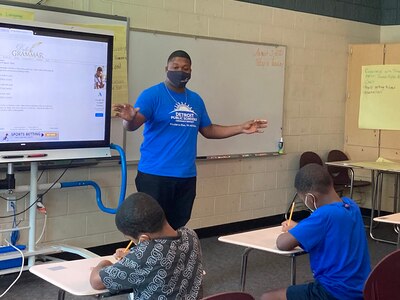

All of this was worth it for Damarco James, who previously worked as a college transition advisor at Osborn High School. James grew up in Benton Harbor, a district with similar academic struggles as DPSCD, and he said he’s motivated by a desire to help students who are growing up in impoverished communities like he did. He’s especially motivated knowing how much students have struggled academically during the pandemic.

“You truly have a chance to make an impact,” James said.

Would-be teachers need support and practice

Traditional teacher preparation programs operated by colleges and universities remain the most common way for aspiring teachers to get certified, accounting for 75% of all enrollment in 2019.

But Shannon Holston, chief of policy and programs at the National Council on Teacher Quality, said alternative certification programs are growing quickly, particularly those operated by non-higher education institutions such as school districts.

She attributes the growth to several factors: The decline in enrollment in traditional preparation programs has disrupted the routes school districts traditionally relied upon for new teachers. Some people interested in teaching see the alternative programs as a better option, because it’s a quicker and cheaper route to the classroom.

Just as important: Some local districts “just haven’t been having their needs met” by traditional routes, Holston said. “To ensure that they have teachers that are prepared in the way they want them to be prepared, they start their own program.”

Holston said research on alternative certification programs has been difficult to analyze because the programs are so different.

“There is some data on some programs that are effective. There are other programs that are on probation because they’re not meeting certain outcomes.”

She said successful programs offer strong coaching that helps the new teachers grow, but also have mechanisms in place to dismiss those that aren’t improving. Programs also should have rigorous admissions requirements and a teaching experience similar to student teaching so that fellows get to work with students. Programs vary on the length of such experiences. In some cases, it lasts a year. In others, it’s a summer school program.

In some programs, attendees come in with no classroom experience, and that concerns Holston. It’s imperative that these aspiring teachers spend extended time teaching in a classroom to gauge if this is the career for them.

“Sometimes people figure out that’s not what they want to do. We’d rather them figure that out in July rather than September.”

Holston, who reviewed online information about the Detroit district program, said she’s encouraged by several features, including requiring fellows to take a science of reading course and calling for two coaching visits and an administrative visit each month.

“That ongoing support is really important,” Holston said.

Program seeks to mirror district demographics

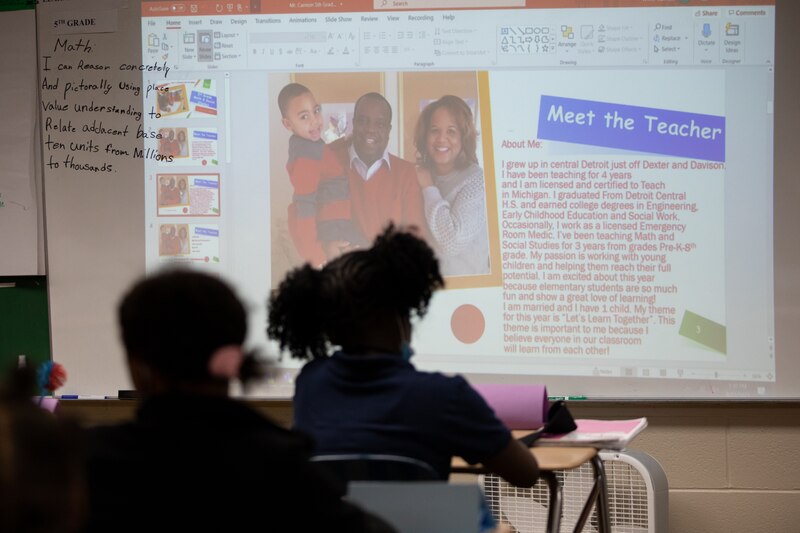

Cannon, a Detroit and district native whose path to the classroom came after a 20-year career as an engineer and a few more years exploring social work, is big on creating a positive atmosphere in his classroom. He introduced the sixth graders to a South African word that is central to his teaching philosophy: Ubuntu. Loosely, it means, “I am because we are.”

For a first-year teacher, Cannon seemed comfortable leading a classroom of middle school students. He told them about his background, played a video that showed young people persevering against incredible odds, and emphasized that he was connected with them and they have to work together for everyone to succeed.

“You’re all going to teach me a lot more than I’m going to teach you.”

In Cassandra Tapia’s second grade summer school classroom, students participatedT in a “me too” game that revealed some common interests.

“I like robots,” one girl stood up and said.

“Me too,” responded most of her classmates.

“I like soccer,” said another.

“Me too,” the class responded.

Before she became a fellow teaching at Munger Elementary-Middle School, Tapia spent a year there as an academic interventionist, tutoring students who needed the most help.

Tapia said that one year working with Munger students was enough to “completely change my perspective” of what she wanted to do as a career.

Chalkbeat sat down with Tapia, Cannon, and James on one of the last days of summer school as the fellows were looking ahead to the beginning of the school year. They said they felt the academy prepared them for the challenges they would face in the classroom.

“I’m excited,” Tapia said. “I feel like I have a good support system. Teaching summer school has given us a glimpse of what to expect.”

“This program gives us everything that a brand-new teacher who went through a teacher prep program wishes that they had,” James added. “That’s the best way I can describe it.”

Tamara Johnson, director of the On the Rise Academy, said selecting candidates who are willing to grow and understand the culture of Detroit and its residents is what will make the program successful. The summer institute focuses on the history of the city and district. At one point, the fellows teamed up for a scavenger hunt downtown.. They also learned about the students they’ll be teaching.

“You want to be a part of that community and not have preconceived notions and ideas about where our students come from,” said Johnson, who is also the district’s senior director of talent pipelines. “You want to be able to learn with them, build relationships with them. That’s important in any classroom and in order to be able to do that, you have to be willing to learn who they are.”

“We pick people who view our students in a strength based way as opposed to a deficit-based way,” said Jessica Haynes, program supervisor of talent pipelines in the district. “We sought to have our demographics in On the Rise Academy mirror the demographics of our students in the district.”

Alternative certification programs have done what traditional programs have struggled to accomplish: Recruit diverse candidates into the profession. Just 30% of students enrolled in traditional programs are non-white, while more than half of those in alternative certification programs are non-white, according to data Vitti shared during the recent school board meeting. In the Detroit program, about 90% of those enrolled are non-white.

Meanwhile, the program could help boost the number of black male teachers, something districts across the country are trying to achieve. About 23% of those enrolled in On the Rise are black men. The district’s current population of black male teachers is 13%, Vitti said.

Ready to teach — and to learn

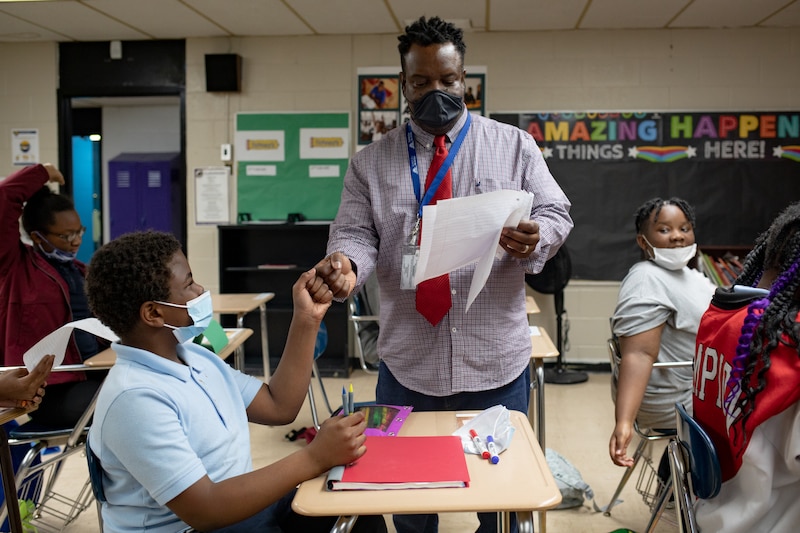

Two weeks into the beginning of the school year, Cannon was feeling good about his decision to teach. He was developing good relationships with his students, and he felt that the lessons he learned about creating a positive classroom culture were paying off. The fellows learned that community circles — when students and their teacher come together in a circle to talk — is one way they can build that positive culture.

A positive classroom culture and strong classroom management skills are crucial skills for success and were key focuses of the summer academy. Poor classroom management skills is one of the reasons new teachers leave the profession too soon, Johnson said.

“We know if the teachers can run a really well-managed room, all of the academic parts are going to come so much easier. And then we can keep them in the district, in classrooms, and make them better academic teachers because they have the management part together.”

Tapia agreed.

“Your lesson can be perfect but if you can’t manage that class, you can’t have 100% participation,” Tapia said. “If students can’t respect and trust you, you’re not going to teach them.”

For Cannon, the biggest challenge has been trying to help students who are far behind academically.

“It’s hard for me to see it. I feel this responsibility to catch you up immediately and it’s not going to happen that way.”

At that point in the school year, he had spent a lot of time focused on classroom rules and procedures and seeing where students stood academically.

On a recent day when Chalkbeat visited with Cannon and the group of sixth graders, he spent some time emphasizing what he hopes to see from students. He showed a short video about a boy who had persevered against a lot of odds. And then he turned to the students.

“That’s the kind of perseverance we’re looking for from all of you,” he told them. “We all have to find a way to make it through.

“Who is it up to?” he asked the students. The responses were varied.

“Us.”

“And me,” Cannon replied, which prompted this response from a student:

“All of us.”