Latrese Taylor hastily scrambled Thursday evening to make sure her children would be set for the first of three remote Fridays, something she hardly thought about since learning was all remote last year.

“It was a bumpy start to our day,” Taylor told Chalkbeat Friday morning. The mother of three Detroit students had to ensure each of her sons was equipped with a working device to communicate with their teachers and classmates.

“It’s been a bit overwhelming because I couldn’t get the day off work.”

But Taylor said last year’s remote learning experience, in spite of its challenges, “prepared us to be ready for whatever the day may hold.”

“Though our day started with some challenges, we were more patient with overcoming obstacles,” she said.

“Last year, the setting was unfamiliar. .... Friday flowed with focus and a sense of comfort.”

The Detroit school district canceled in-person classes for three Fridays in December to address concerns about the need for a mental health break, rising COVID cases, and to have more time to clean buildings. Many parents praised the decision when it was announced, but the district was heavily criticized for the decision to go remote from people who said it would hurt students academically, and some who questioned whether any learning would happen.

Across Michigan, other school districts such as Southfield and Grand Rapids have canceled classes or moved to remote learning due to COVID outbreaks as well as staffing shortages.

Even with the experience of being virtual all last year, the Taylors faced difficulties going to online learning once a week.

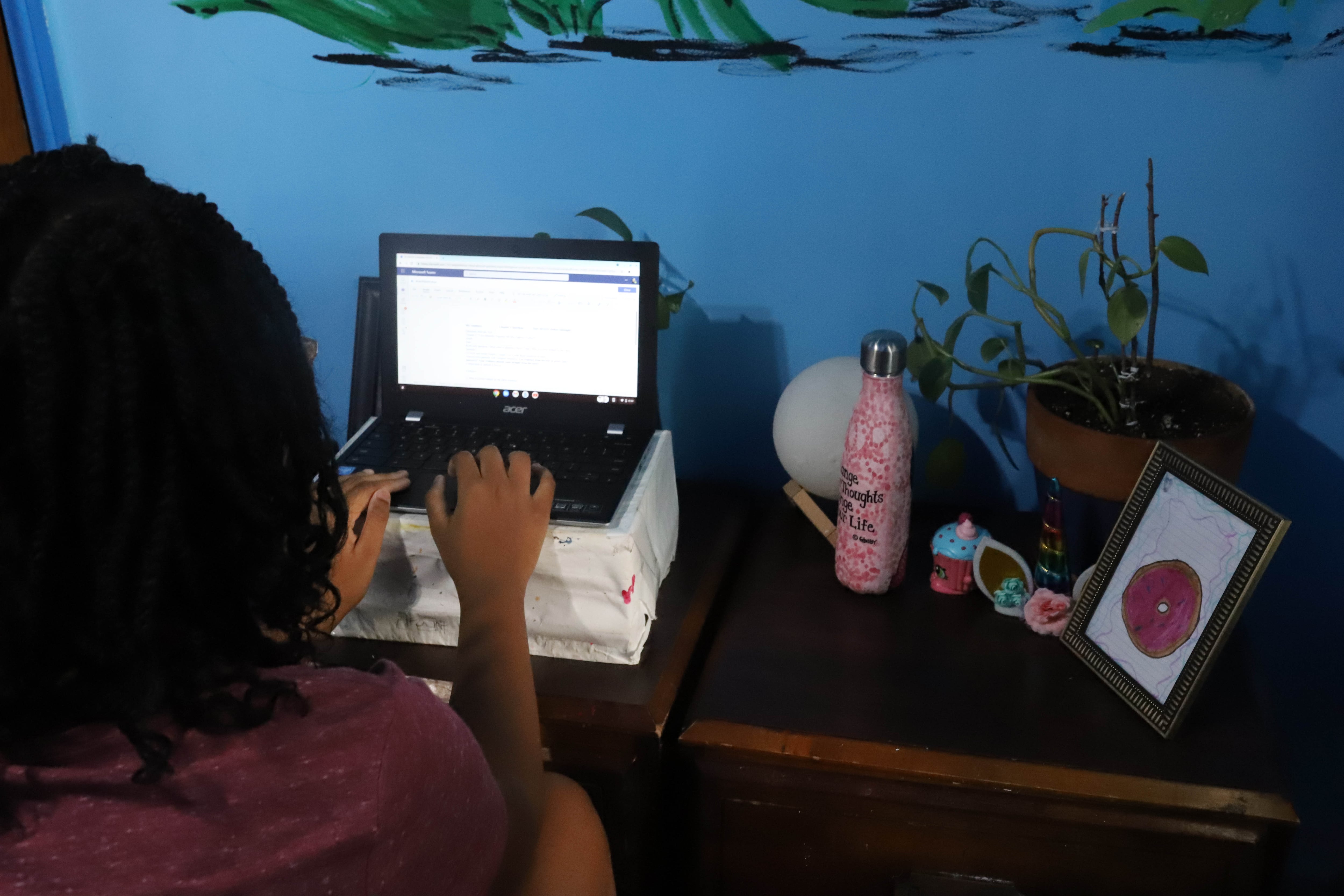

Last year, Taylor didn’t have enough devices for her children. This year she had saved up money to purchase a desktop computer, so the family was better prepared to do the online work. But while her fifth grader was able to work on the family desktop computer, another found that his device was broken.

Taylor managed to help her youngest son log in and upload his class assignments on her cell phone before she went to work. As the day went on she continued to monitor their learning via her phone.

It wasn’t until the day before remote Friday that Taylor learned that she could get tech support at one of the district’s technology hubs. The information had been passed along to her sons’ emails ahead of time, but Taylor had not been checking their emails.

In another household, Damarion Treadwell sat at his family dining room table with his laptop in front of him and a notebook and pencil beside him. The Detroit Martin Luther King High School student looked forward to the first of three remote Fridays.

Damarion feels he’s adjusted to online learning. Compared with last year, most of his teachers have a better handle on how they want to set up and plan out their virtual classes. On Friday, both his science and history teacher provided live instruction he could follow along with at home.

“Education-wise, I still feel on track as far as getting work done. But high school-wise ... communication, being social with people ... I feel like that’s a thing that virtual school won’t give,” he said.

In a school year marked as a rebound for school districts battered by the stressors of virtual learning, the move to remote learning days indicated just how challenging it has been to keep students in person as COVID outbreaks and staff shortages have been ongoing.

Taylor was on board with the decision to move to virtual Fridays in light of her experience contracting COVID earlier this year. She spent a portion of the remote instruction year going in and out of the hospital as her oldest son, an adult, supervised the younger boys while they learned at home.

This school year alone, she added, one of her sons was forced to quarantine after coming into close contact with a classmate.

“I personally take the seriousness of all this to heart,” Taylor said.

Damarion isn’t fully convinced the Detroit school district needs to add more online learning days. The junior has already been vaccinated, he says, and hasn’t felt the same fears about staying in person for the school year as his father and aunt had when the district began to report school closures due to COVID outbreaks in late October.

“They were talking about how students should not go back to school until more people get the vaccine,” Damarion said. Vaccination rates across Detroit remain low: About 43% city residents ages 5 and older have received at least one vaccine dose, behind nearby county and statewide figures.

Instead, he suggested, the district should work to optimize classrooms so that students can maintain social distancing.

“It’s good how it is now until cases increase, then it needs to go back to virtual but if they don’t we can just keep it like this.”