Every once in a while, Latrell Maxwell turns to the photo of Thomas Fields that sits on the dresser in his bedroom, and he has the kind of conversation he used to have when Fields was alive.

He tells Fields about his school day. He talks through any problems he’s having. And he imagines Fields giving him the kind of pep talk that made so many students feel seen at Paul Robeson Malcolm X Academy in the Detroit school district.

Do well in school, Fields would often tell them. Make your education a priority. Don’t give up.

“It feels good to know that even though he’s not presently here, he’s spiritually here,” said Latrell, an eighth grader at the school. “I just try to remember all the good times we had.”

It’s been a long, emotional year since Fields died from coronavirus complications, leaving a deep void at the school where he was the school culture facilitator, a role that required him to work with students who have behavior problems. In the midst of a harrowing public health crisis that hit the city particularly hard, this tight-knit school community has sought to cope with his death and honor his memory.

But the grieving process has been challenging. The school, which has an African-centered focus, hasn’t held face-to-face classes for a year. And for parent leaders like Aliya Moore, who are used to seeing students regularly in the building, that means “I still can’t wrap my arms around our babies.”

Field’s death came March 30, 20 days after the first positive COVID-19 case was recorded in Michigan, and shortly after schools shut their buildings and shifted to remote learning. In the wake of his death, the Detroit Public Schools Community District provided counseling to students and staff. The PTA held a socially-distanced outdoor memorial and released balloons. Graduating students each received a key chain with a photo of Fields.

But many are still grieving, and school leaders know they need to continue helping students and staff cope with the loss of the staff member who often cheered them up.

In the year since his death, Field’s name frequently comes up — in classroom chats, during a Black History Month celebration, and in everyday conversations. Fields, Principal Jeffery Robinson said, managed to connect with students in ways others couldn’t. It’s one of the reasons Robinson had frequently encouraged Fields to pursue a teaching degree.

“He was that good,” Robinson said.

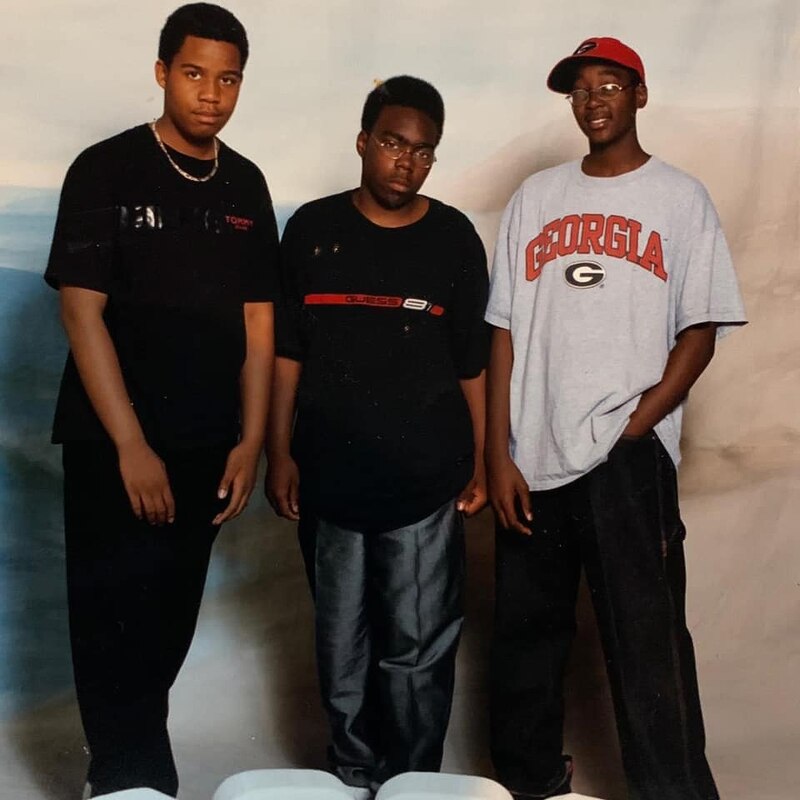

Fields, who was 32, didn’t have a long tenure at the school, having been hired in 2019. But he already had a deep connection.

Years ago, when Malcolm X Academy and Paul Robeson Academy were separate schools with a focus on African-centered education, Fields was a student attending Malcolm X. Robinson, a longtime educator in Detroit, was a teacher at the school. He and Fields remained in contact over the years, and Robinson has described hiring Fields as a proud moment.

Schools like these were built around the idea that Black children need to understand their history and culture to succeed academically. Such schools once thrived in Detroit, and the model was replicated elsewhere in the country. But now, there are only a few of these schools remaining in the city. More than a decade ago, Malcolm X and Paul Robeson were combined, with Robinson taking on the principal’s role. He’s led the school for 12 years.

It was at Malcolm X that Fields learned about the importance of community and the school family. Adults are called Mama and Baba, African terms for mother and father. And the schools place a premium on developing connections between the staff and families that help raise strong children.

By the time Robinson approached Fields to work at the school, the latter had already earned a degree from Grambling State University and was a U.S. Navy veteran. He spent most of his time working closely with students who got into trouble because of bad behavior, giving them tools and encouragement to make better choices. Fields, Robinson said, took the job because he wanted to give back to the school that had given him so much.

He had a knack for reaching some of the most troubled children and he became so popular that at least one boy got in trouble on purpose so he could spend time with Fields.

“He never forgot the feelings and emotions of being a youth,” Moore, the PTA leader, said.

One day in late September, weeks after the school year had begun, Robinson and several staff members were hit with a wave of grief while in search of a place to store technology equipment.

Long before the pandemic, Fields had pushed Robinson to OK the purchase of board games and video games that would be an incentive for good behavior. Robinson had given his blessing for the purchase earlier in 2020, then thought little of it. So when he opened the door to the storage room, he saw that not only had the games arrived, but Fields had organized and marked them with numbers.

“All of us stood there and cried,” Robinson said. “Nobody had been in that room since Thomas had been there.”

It was another reminder of how much they miss Fields. He was the person who greeted students at the front entrance every morning, hyping them up for the day’s lessons. He played basketball with the kids and taught them old-school games like red light, green light. He was someone who encouraged and inspired students. And Fields, an avid cook who frequently posted videos of himself in the kitchen, had made plans to teach students how to cook.

Just last week, Melissa Redman, Latrell’s mother, recalled running into Fields on the last day classes were in session in the building. Fields was in the gym during his lunch break, cracking jokes. With the anniversary of his death approaching, Redman has been thinking about that day lately, her thoughts often turning to Fields..

“I keep his picture around my neck,” she said, referring to a blue lanyard with Field’s picture attached that she wears every day. “I don’t want to forget what happened a year ago. I don’t want to forget him. I always want to keep his name lifted.”

Fields’ loss came at a devastating time for the city of Detroit, which was confronted with many COVID-19 cases and deaths in the early months of the pandemic.

The passings reverberated across the city as some prominent community leaders lost their battles with the virus. In school communities, students, staff, parents — many of them lost relatives or knew someone who died.

Robinson felt the deaths intensely. Just days after Fields died, Robinson suffered an even bigger personal loss. His mother, Evelyn Grace Robinson, died alone in a city hospital. It was Easter Sunday, and she had COVID-19. The year before, his granddaughter and a grandmother had died.

Also a minister, Robinson has officiated at nearly 70 funerals in the last year. In a typical year, he does about a dozen.

“I haven’t properly grieved,” Robinson said of the deaths of his mother, Fields, and so many others. “What I know of psychology and being an educator for 30 years … I know I have to. It has been a rough couple of years.”

Robinson said he finds solace in seeing to the needs of others. The school has been handing out food boxes to those who need it.

“That’s where I sort of grounded myself,” he said.

There is a wall outside the main office at Paul Robeson Malcolm X that pays tribute to people who have passed who had a connection to the school. Soon, Robinson will add Fields to that wall. He knows his students need closure, for many different reasons.

“Our kids have lost people, and they’re going to bring that (grief) back,” Robinson said.

The school is one of a small number in the Detroit district that hasn’t returned to face-to-face instruction — a decision Robinson made with input from parents. Most parents and teachers, he said, aren’t ready to return due to safety concerns.

Robinson wants the school to hold some type of event that will help students get the closure they need. It may be another balloon release ceremony. It may be something else, like a tree planting.

“We have to do something,” Moore said. “It’s about healing and it’s about mental health. I have faith that between administrators, teachers and us being parents, we will wrap our arms around these kids and focus on their mental health.”

But she knows that the first day back to in-person instruction — whenever that will be — will be a difficult one, since students became so accustomed to seeing Fields greeting them at the door.

“To come to the door and no Baba Fields? …”

Latrell will be graduating from Paul Robeson Malcolm X this year and heading to Cass Technical High School in the fall. He said he won’t forget Fields, and how well he understood students.

“We talk about him all the time,” Latrell said. “We just talk about all the good times we had with him. He used to play basketball with us. He helped us with our science fair projects.”

Moore said it’s important for students to understand that one of the best ways they can honor his memory is to remember what he taught them.

“He’s still with us,” she said. “Your behavior, what you do moving forward, will continue his legacy.”

Robinson will need to hire a new school culture facilitator for the upcoming school year. But he doesn’t like to say Fields will be replaced. That, he said, is impossible.

“I tell the students, ‘Close the book, but remember the story.’ “