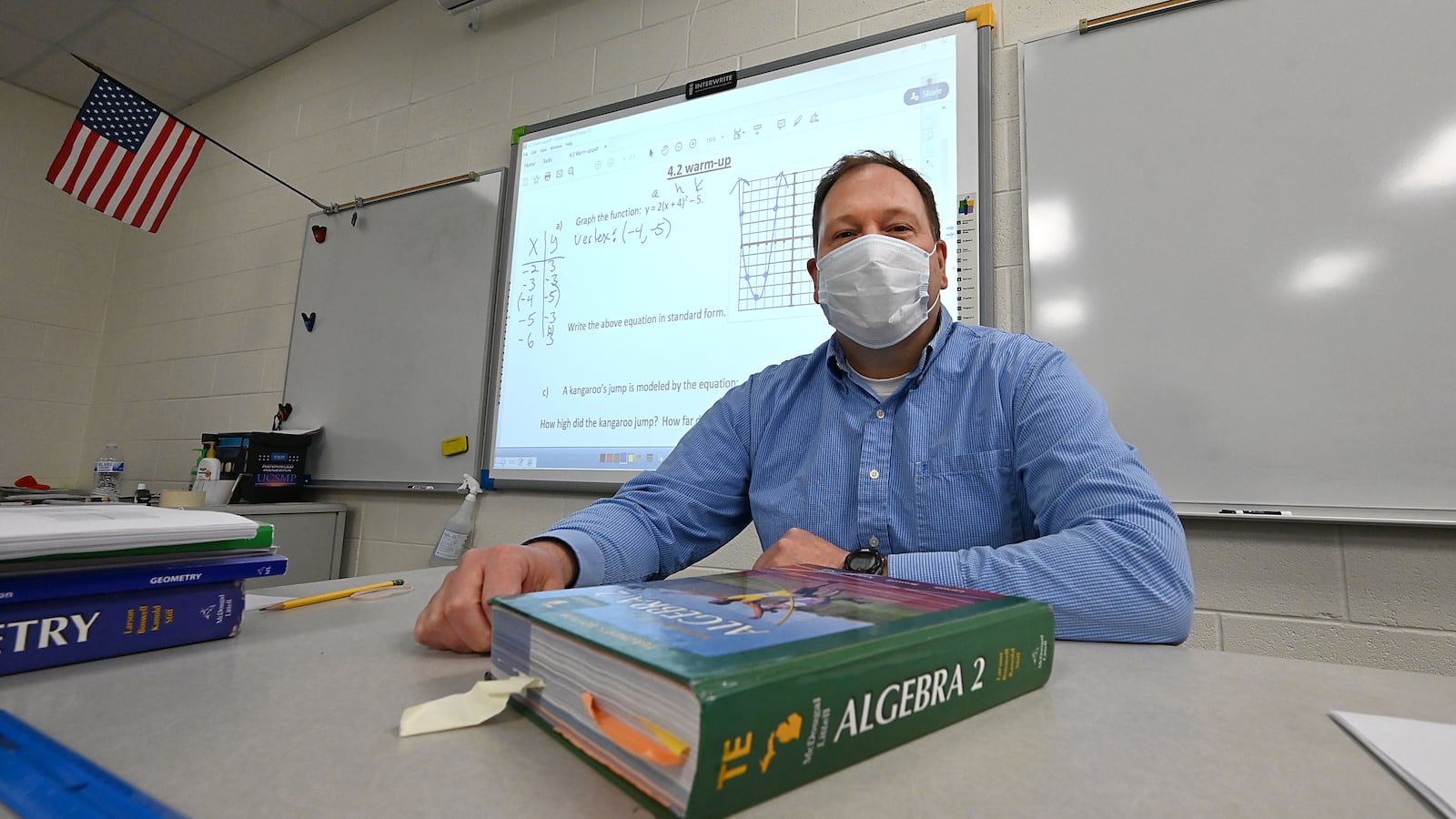

Dwight Pierson stands in his high school classroom in the mid-Michigan town of St. John’s wearing a telephone headset each day while teaching logarithms and polynomials.

In one ear, he’s got one-third of his class talking to him via Zoom, the videoconferencing platform that has become synonymous with the coronavirus pandemic.

In Pierson’s open ear, he’s fielding questions from the rest of students who are masked up in the classroom with him.

It’s a daunting way to teach Algebra II to sophomores and juniors, Pierson said.

“It’s like you’re talking to a wall sometimes,” he said. “It’s a little bit of a circus every day.”

After 29 years on the job, Pierson, 51, is not sure he wants to return to the “circus” next year, knowing that schools will likely have to continue offering a virtual distance-learning option that forces him to effectively teach two different classes at once.

Pierson is one of 18,629 K-12 public school teachers in Michigan who are eligible to retire at any point and collect a full pension, accounting for one in four of the state’s teachers actively working, according to the Michigan Public School Employees’ Retirement System (MPSERS).

According to MPSERS data, an additional 11,975 teachers have 20 to 25 years of service and are close to being eligible to retire early, depending on whether they have bought up to five years of service credit used to calculate lifetime pensions.

The stress and chaos of teaching during a once-in-a-century pandemic has Pierson and others weighing a departure from public education, stirring fears of a mass exodus that could hobble public schools in Michigan without an influx of new teachers in a talent pipeline that was diminishing well before the pandemic.

“The pandemic is a game-changer,” Pierson said. “I think there’s going to be record retirements. That would be my prediction.”

K-12 schools in Michigan are already experiencing critical shortages of teachers across all subjects, particularly math, science and special education.

“It didn’t pop up overnight during COVID,” said Tina Kerr, executive director of the Michigan Association of School Administrators. “This is certainly a problem that’s been very alarming to us in the past.”

But the pandemic may have exacerbated an emerging crisis.

From August through February, there was a 44 percent increase in midyear retirements compared to the same period in 2019-2020 as 749 teachers left public school classrooms in the middle of the school year, state data show.

“Not only do we have a lot of retirements in the last year, but we’re going to have a lot more,” said state Rep. Pamela Hornberger, chair of the House Education Committee who spent 22 years teaching in the East China School District.

Active and retired educators are warning of a new wave of retirements coming this summer after teachers get through this current school year, which, for some districts, has been marked by multiple starts and stops for in-person instruction because of COVID-19 outbreaks and mass quarantines.

“COVID has tipped the scales,” said Amy Moening, who retired from Roseville Community Schools last June after 28 years of teaching first grade. “What teachers are being asked to do is superhuman.”

“Most teachers say they’re doing twice as much work they were doing pre-COVID with even less planning time,” she added.

Moening, who turns 55 in November, had announced her plans to retire before the pandemic hit.

She said her departure from full-time teaching came after years of mounting mandates from lawmakers and by-the-book administrators that eroded her classroom autonomy.

“The lack of trust in my professionalism was just killer,” said Moening, who is now a K-5 reading tutor for an online school. “It’s just very frustrating for a teacher when you know what’s best for kids.”

While mid-year retirements have risen considerably, some superintendents expect this summer’s retirements and resignations to level off or decline because of earlier-than-planned departures.

“We’ve probably had more teachers resign/retire, more staff members resign/retire in the middle of the year than we’ve ever had before,” said Gary Niehaus, superintendent of Grosse Pointe Public Schools.

Grosse Pointe schools’ union contract required teachers to declare their intent to retire by March 1, Niehaus said.

“Honestly, we had probably the fewest retirements we’ve had in a really long time just simply because we’ve been doing it all year long,” said Niehaus, who himself is retiring at the end of this school year.

‘It’s only getting worse’

Teacher shortages in Michigan have been a building for years, educators say, as baby boomer teachers retire and the state’s teaching colleges see fewer and fewer students pursuing a degree in education.

Marc Meyers, 55, retired in August after 32 years as an elementary music school teacher in Walled Lake Consolidated Schools.

Meyers had many reasons why he decided to retire in his mid-50s instead of working until he’s 60.

Chief among them were mounting mandates on the teaching profession while his overall compensation diminished. Meyers said his 2013 compensation ended up being his highest annual salary used to determine his pension seven years later.

Meyers said mounting job expectations took a toll on him.

“I would dread opening emails every day because it felt like every day you could expect an email saying, ‘Oh, now you need to do this, we’re not going to pay you more, we’re not going to do anything to make your life better, we’re just going to give you more work and you’ve got to do it if you want to keep your job,’” Meyers said. “And that kind of thing really frustrated me.”

The retirement trend isn’t confined to teachers.

From August through February, there was a 33 percent increase in retirements compared to the same period in 2019-2020 among school personnel who are not teachers — superintendents, principals, counselors, paraprofessionals and other school support staff.

At the Michigan Association of School Administrators’ mid-winter conference in January, 36 superintendents were recognized for their retirement from the profession.

“That was just in January,” Kerr said. “Since then, there have been more. ... It’s not a new problem, but I think that it’s only getting worse.”

Back in the classroom

To fill teaching jobs in Michigan, some lawmakers in both parties with backgrounds in education are proposing a radical idea: Let retired teachers come back to teach full-time while collecting their pension checks.

A bill pending in the House Education Committee would let a retired teacher return to the classroom to fill a position on a critical teacher shortage list or substitute teach without having their pension or retiree health care reduced.

The legislation, House Bill 4375, also would let a school district rehire a retired teacher without having to make additional payments to the pension fund on their behalf to cover unfunded liabilities.

The legislation could effectively encourage double-dipping, but Hornberger said it may be necessary “until there are more people who want to go into the profession.”

“At this point, I’m open to anything,” Hornberger said. “I would rather have a retired teacher come in and sub than someone’s aunt who is looking for a job and they think they’re babysitting.”

Administrators have retired in the past and come back to work for the same school district as contractors while collecting pensions.

“It was a gravy train for them, so you can’t blame them,” Hornberger said. “[But] we’re going to have to do something.”

MASA has joined other education lobby groups seeking greater flexibility for school districts to hire retired teachers who are actively collecting pension checks.

“A teacher should be able to come back if they cannot find a qualified person to fill the position in question,” Kerr said.

In the coming months, veteran teachers will have to begin informing their principals if they plan to retire before August, when the new school year begins. Because of the way teacher salaries are paid, about three-in-five teachers begin their retirements in July each year, state data show.

In St. John’s, Pierson faces an April 1 deadline to decide whether he wants to be back in front of the whiteboard next fall teaching logarithms and polynomials — likely talking to two different classes at once.

The temptation to retire comfortably in his mid-50s is growing. His wife, Anne, retired last June after teaching English and language arts in rural Fowler for nearly 27 years.

Pierson said it’s “a tough decision” whether to leave his classroom in June or stick it out for another year.

“I still like teaching. I still like being in school,” he said. “But it does wear on you. You’re just not sure if you go one more year if you’ll still like it.”

Chad Livengood is the senior editor at Crain’s Detroit Business.