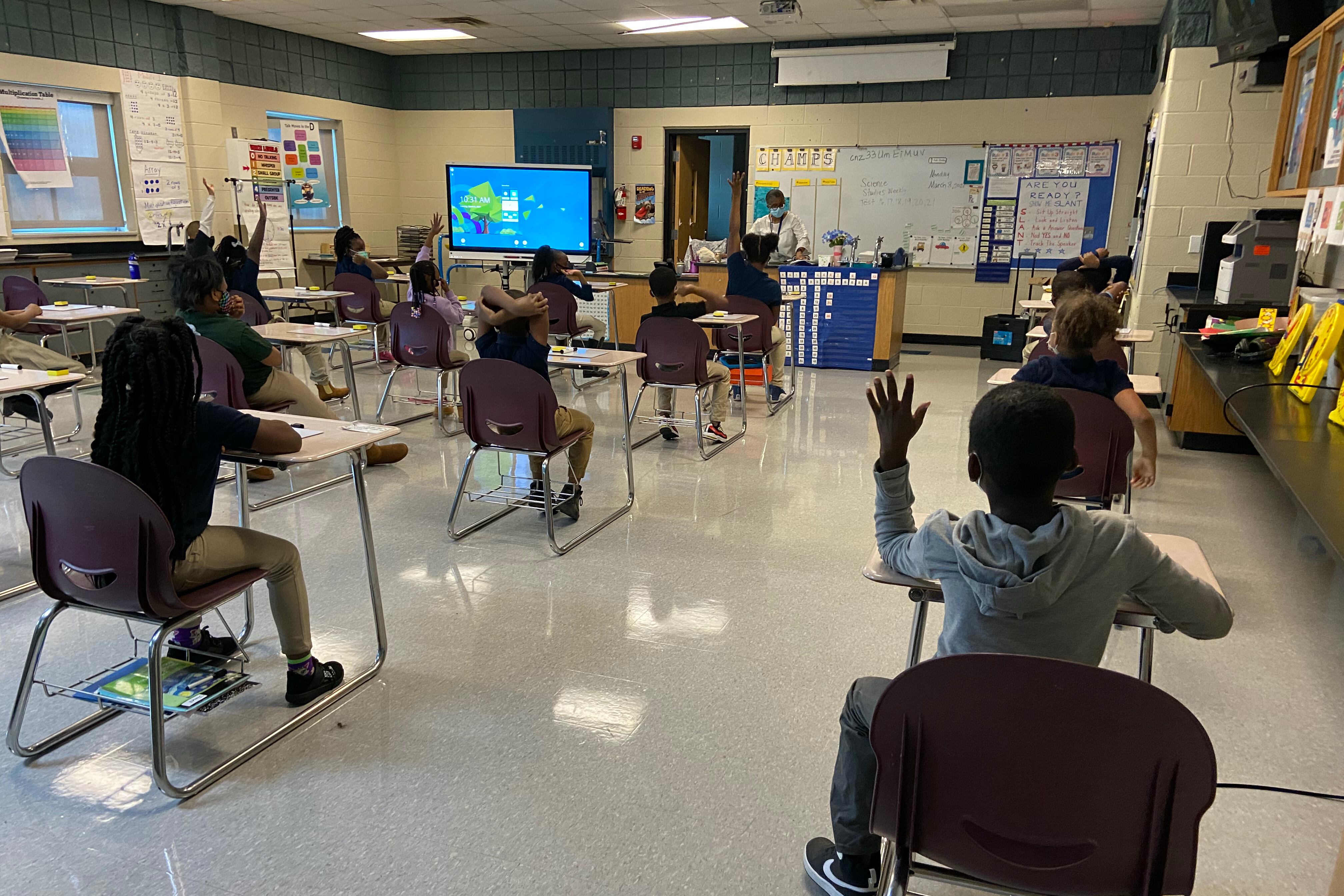

Sultana Gambrell had only been back in her classroom at Ronald Brown Academy for a couple of hours, but she was already on a roll with a lesson about the water cycle.

“High five!” she called out to a student who’d just given a correct answer. She started to move toward him, then thought twice.

“Well, we can’t touch, but high five!” she said, miming the gesture to her student, who returned it.

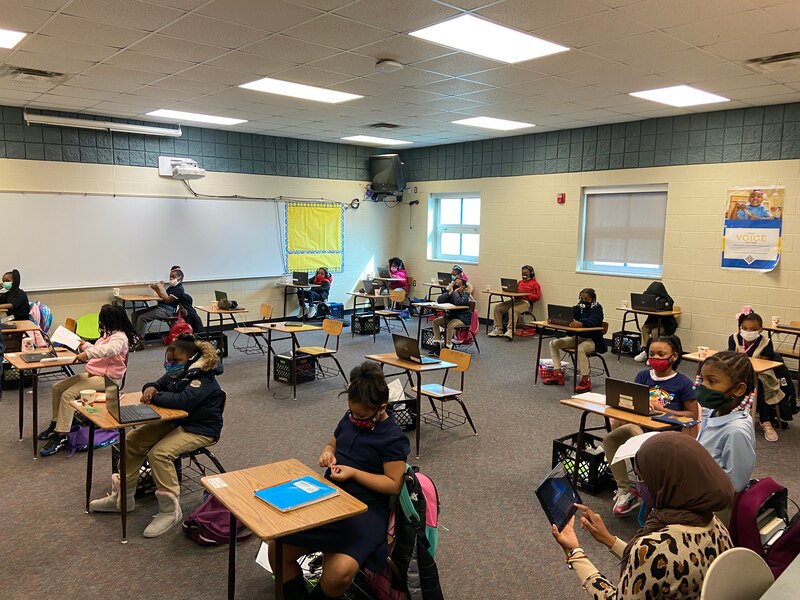

It wasn’t quite business as usual in the Detroit Public Schools Community District on Monday as teachers returned to classrooms in Detroit for the first time in months. Staff kept a close eye on students to make sure they stayed six feet apart and wore their masks over their noses. And many students still took some lessons online because not enough teachers agreed to return to their classrooms to meet demand from families.

Even without full attendance, Monday marked another step toward a pre-pandemic normal. An estimated 20,000 students were expected to report to school, or about 40% of the total. That’s about twice as many as last fall, when the district reopened classrooms until rising COVID-19 cases forced a suspension in mid-November.

At the same time, the district expected 20% of teachers to report to their classrooms, ensuring that some students who wanted in-person instruction wouldn’t get it. Nikolai Vitti, district superintendent, said he wouldn’t know how many teachers and students showed up on Monday until later in the week.

“I was ecstatic,” said Sonya Haynes, an English teacher at Brenda Scott Academy, of the return to work. She hasn’t been vaccinated yet, but she said she strongly prefers teaching in-person to teaching virtually. “I was like a little kid last night getting ready for school. Clothes ironed, lunch made.”

Vitti visited schools on Monday morning with Terrence Martin, president of the Detroit Federation of Teachers, the district’s largest educators union.

Both said they expect more educators to come back to work in person in coming weeks. Earlier in the pandemic, the district and union agreed that teachers would be able to choose whether to work in person or virtually. Other staff, including assistant principals, deans, and paraprofessionals, were required to report to work on Feb. 24.

“My biggest concern is that we’re not completely matching student demand with teacher willingness to come into the classroom,” Vitti said. “But I’m optimistic that over the next weeks or months, that when these teachers talk to other teachers about the safety standards that we have in place, more will come back.”

Guidelines from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention say schools can be opened safely even if teachers aren’t vaccinated. However, many teachers are leery of returning to work before receiving the shot.

Health officials in Detroit estimate Detroit health officials estimate that they have vaccinated about 9,000 teachers — including charter school teachers — but federal law prohibits the city from telling the district which teachers have been vaccinated without the teachers’ consent. The district sent a voluntary survey to its roughly 3,800 teachers asking whether they have received vaccines, but so far has received only a few hundred responses.

Vitti said Detroit teachers are particularly concerned about the dangers of the virus because many lost family members in the spring, when the city was hit especially hard.

Despite the agreement between the district and teachers union, some teachers are concerned that they will be forced to work once they are vaccinated, Vitti said. Vitti has said that the district will not require teachers and families to get the vaccine.

Martin, the union president, said the district “has done everything that it can do to ensure safety.”

“I’m seeing mitigation strategies implemented,” he added. “I’m seeing small class sizes, students six feet apart in classrooms. It’s going to take some time for folks to get more comfortable. But I’m pretty confident that we’re going to start to see those numbers increase over the next few weeks.”

When a student comes to school and their teacher doesn’t, the teacher will still give lessons online. For older students, that might mean taking a virtual lesson from their teacher while sitting in a classroom supervised by another adult. The next hour, they might have a face-to-face class with a teacher who opted to return.

For younger students, who often only have one teacher, this can mean spending the day in one of the district’s learning centers. Each school has a center where students can learn virtually at school.

There were more than a dozen students in the learning center at Brenda Scott Academy on Monday. Most had laptops on their tables, while a few read books. Several students weren’t using headphones, and all their teachers’ voices were audible at once.

At Ronald Brown Academy, Michael Foster, a fourth grade math teacher, was teaching students virtually and in person at the same time.

As he walked his students through a lesson on fractions, a voice came from a speaker at the front of the classroom: “I can’t see your screen at all.”

There were a dozen students in Foster’s classroom, and several more had been following the lesson at home. At least one of the virtual students was struggling to stay connected.

Foster tried to keep talking about fractions and fix the problem at the same time.

“How many parts are inside two-fifths?” he asked.

“I can barely hear you,” the student interjected. “I still can’t see the screen.”