King Bethel knew he grew up in a divided city, but it wasn’t until six months ago that he discovered one of the reasons why.

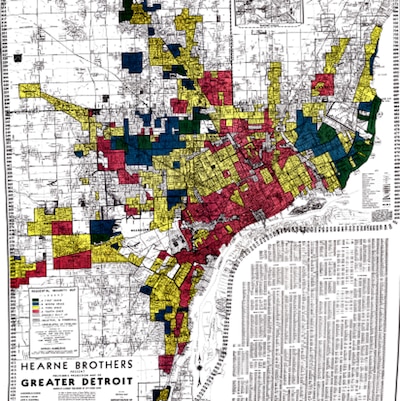

In social studies class, the Detroit ninth grader learned about redlining, a government housing policy that discriminated against people based on their race or ethnicity. The practice, which began in the 1930s, fueled segregation for decades and stripped Black families of generational wealth.

“Nobody tried to help them,” King said.

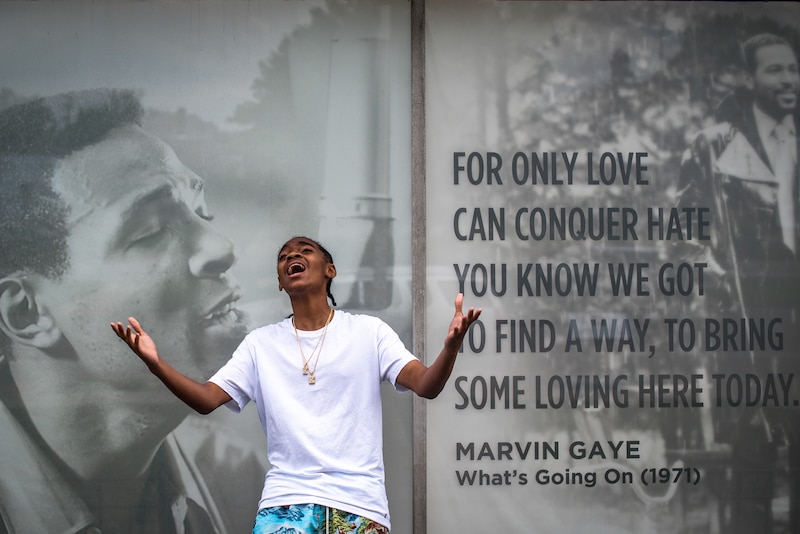

A standout singer, King is used to being noticed for his voice. Starting the year at Detroit School of Arts, he worried about how he would shine from behind a computer screen, and whether he would find an ally on the school staff to support his ambitions to perform. But after a year in which the pandemic upended his schooling and his mother was recovering from COVID, the 15-year-old feels he now better understands the power of his voice — on stage and in the classroom.

He says his empathy and understanding have only broadened because of what he’s learned from teachers and classmates. He’s also emerged as a leader for his peers. It’s given him a more mature and thoughtful perspective and accelerated his passion for activism.

Inspired by the lesson about redlining, King began to do more research about how the racist policies affected families, including his own. He looked up articles online and re-read class materials. He also learned of a painful chapter in his own family’s history when his mother, Netha Johnson, told him how his great-great grandparents experienced discrimination when they searched for a home during the 1960s.

A few days after the history lesson, King sat at his desk and started working on a speech to submit to a national public speaking competition called Project Soapbox. He wanted to share what he had learned, to use his voice in a different way.

“I wasn’t trying to entertain,” he said. “I was trying to teach.”

Instead of thinking about performing for teachers and classmates, King imagined an audience of people in power. He wrote his speech with the same energy he uses to write songs. People needed to understand the urgency of his message: that his neighbors deserved a better quality of life. The topic warranted a more serious tone.

During social studies class, he saw images of multiple Black families living inside of homes that seemed to be falling apart.

“It was terrible like that,” King said.

Beginning in the 1930s, the federal government made maps of major metropolitan areas with colors to denote where it was “safe” to insure mortgages. Black neighborhoods were shaded red to indicate higher risk to lenders, though there was no evidence to support that. King’s family members were affected by the practice in Detroit and Chicago.

Johnson said that when King’s great-great grandfather, Conrad LeCuyer, returned from military service, he and his wife Bertha were trying to purchase a home in the Chicago suburbs, but they were refused opportunities to live in those areas. They ended up finding a home in Englewood, a Chicago neighborhood whose Black population rose in the 1960s in the wake of urban renewal projects that disenfranchised Black residents.

“It was always an obstacle. People of our color weren’t treated fairly,” Johnson said. “To know someone that actually went through these types of events really hit home for King and myself.” Johnson said her relatives still talk about that time.

By learning these family stories, King began weaving the connections of redlining’s past damage to the present day. In writing his speech, King felt he was speaking up on behalf of not only his neighbors but his elders.

“They never had a chance to speak up before,” he said.

Marilyn Griffin, King’s social studies teacher, said she wants to make Detroit history feel relevant to students.

“Oftentimes, history is all about the past,” she said. “And many students don’t relate to it. They’re not interested in it. They don’t see their story in it. They don’t see themselves. They can learn about the American Revolution all day, but they never learn about their own neighborhood.”

Not long after King learned in class about redlining, a national debate erupted over how American students learn about the nation’s history. Lawmakers in more than a dozen states have rushed to enact new laws and policies to shape how history is taught in K-12 classrooms.

Many of those changes have been to ban critical race theory, an academic framework that considers how policies and law perpetuate systemic racism. Most K-12 schools aren’t actually teaching the concept, but the term has become a catchall among those who want to restrict teaching about the lasting effects of slavery and segregation.

Griffin, who’s been an educator for nine years, found the attempts to constrain the teaching of these lessons disheartening. To her, it’s an example of how people fear having instructive conversations on race.

“People are afraid to have them because it makes them uncomfortable, but that’s how we grow as a community, as a society,” she said. “There’s so many different ethnic groups, and histories, and stories to tell that I don’t see it as one history that should exist.”

After practicing his speech in front of relatives and getting feedback from his tutors at a local boxing gym, King recorded it at home a few weeks later.

In the video, he begins with a simple introduction: His name is King Bethel. He is 15 years old. He was born and raised on Detroit’s east side.

His large, expressive eyes lock into the camera, and he makes small but emphatic hand gestures.

King says people know what systemic racism is, but not as many may know about redlining, which he argues played a key role in the economic disinvestment he saw across the neighborhood he loves.

“There’s abandoned lots, houses, churches, stores, but no help. We need help.

He demands more money to build new homes and demolish blighted buildings that keep people unsafe.

He then asks those watching or listening to “look, ponder, and imagine what the city would be like if it had new, flourishing businesses and homes.”

King has imagined what those things could be: a grocery store, a playground, coffee shops, gyms, a community center.

In the Detroit Public Schools Community District, the school year has been marked by low engagement, higher chronic absenteeism, and higher failure rates. District officials plan to offer more face-to-face instruction next year, although the success of those efforts will likely depend on the number of teachers willing to return to physical classrooms.

Superintendent Nikolai Vitti has said he expects the majority of district teachers to work in person next school year, which will be crucial to boosting the district’s enrollment. The school board also recently approved the creation of a separate virtual school.

With the city’s COVID-19 vaccination rates slowly climbing and Michigan’s easing of major pandemic restrictions, King’s school organized some activities on campus, including a dance concert, outdoor prom and graduation, and a social event for freshmen.

King, however, wasn’t able to participate in those activities. He spent the last weeks of freshman year at his grandmother’s house on the South Side of Chicago.

For social studies, he had to write about what he wants his life to look like in the next five years.

King wants to buy his own home. He imagines his mom, dad, and little brother living with him. It could be in Detroit. Or maybe California.

Those dreams are still years away. Right now, even in a post-lockdown world, the family still sticks to strict safety precautions.

King is eager to return to the physical classroom, but his mother isn’t ready for him to go back. Wearing masks and social distancing are not strong enough assurances of safety for her. After recovering from the virus more than a year ago, she said she is still living with its complications, including breathing problems.

“It’s just scary,” she said. “I don’t want my children to experience the things that I did.”

She promised King she would do more research and see how things play out. She may re-evaluate the possibility of a return later on. Either way, King said he respects his mother’s decision.

Even with all-remote instruction, King said ninth grade was the game-changing year he’d anticipated. He better understood the power of his voice and his experiences. He also better understood who he was speaking for after learning about what families, including his own, have endured because of practices like redlining.

In late spring, King found out his redlining speech placed top 12 in the nation in the contest he had entered.

“I felt like my voice was heard,” he said. “In my heart, I knew I did the right thing.”