Students circled up in the lobby of a Detroit high school on a hot day in July to make noise together.

“What up doe?” they chanted. “Are you hype? Yeah I’m hype!”

As the sounds of the call-and-response washed over Tyrese Barns, a rising freshman at Davis Aerospace Academy in the Detroit Public Schools Community District, he says he began to feel ready — even eager — for September.

Barns has struggled academically during the pandemic. He says the worst part of virtual learning over the last year was the social isolation. He dreaded the prospect of starting high school and returning to in-person learning at the same time.

Across Michigan, students like Barns got more opportunities this summer to learn and connect with their peers than usual thanks to billions in federal COVID relief funding that aim to help students recover academically and emotionally from a school year turned upside down by the pandemic.

The return to classrooms for Detroit students began in July with expanded summer school classes, academic programs designed to help students accelerate their learning after a challenging year of virtual instruction. After morning classes, students could choose from an unusually wide array of enrichment programs, including cooking classes and robotics workshops. The district contracted with a number of community agencies in order to provide summer programming for more students.

The goal is to help build students’ skills and confidence — and reconnect them with their peers after an isolating year.

“At a minimal level, it gave students an opportunity to interact with each other again and become familiar and comfortable with school again,” said Detroit Superintendent Nikolai Vitti in an email. “It also addressed learning loss, inactivity, and isolation. Lastly, it will help to increase enrollment for the fall.”

Barns said his enrichment program had convinced him that “it’s going to be fun to be back in school. He added: “They really helped my social well-being.”

Most DPSCD students haven’t learned in a classroom since the pandemic began in March 2020. Learning online was less effective for many students, and many were also dealing with loved ones falling ill with COVID and being isolated from their friends.

The result was an alarming level of mental health problems among young people. In a recent national survey, parents of children who were learning virtually during the last year were especially likely to report that their children’s mental health had worsened. Mental health crises among teens spiked by nearly one third during the pandemic, according to a separate report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Over the year I just stopped caring about a lot of things,” said Nevyah Anderson, an 11th grader at Old Redford Academy, a charter school in Detroit.

Improving students’ emotional well-being is one key use for $6 billion in federal relief dollars sent to Michigan to help schools and students recover. The Detroit district, among other districts across the state, has pledged to use part of its share of the funding to hire more social workers and school psychologists.

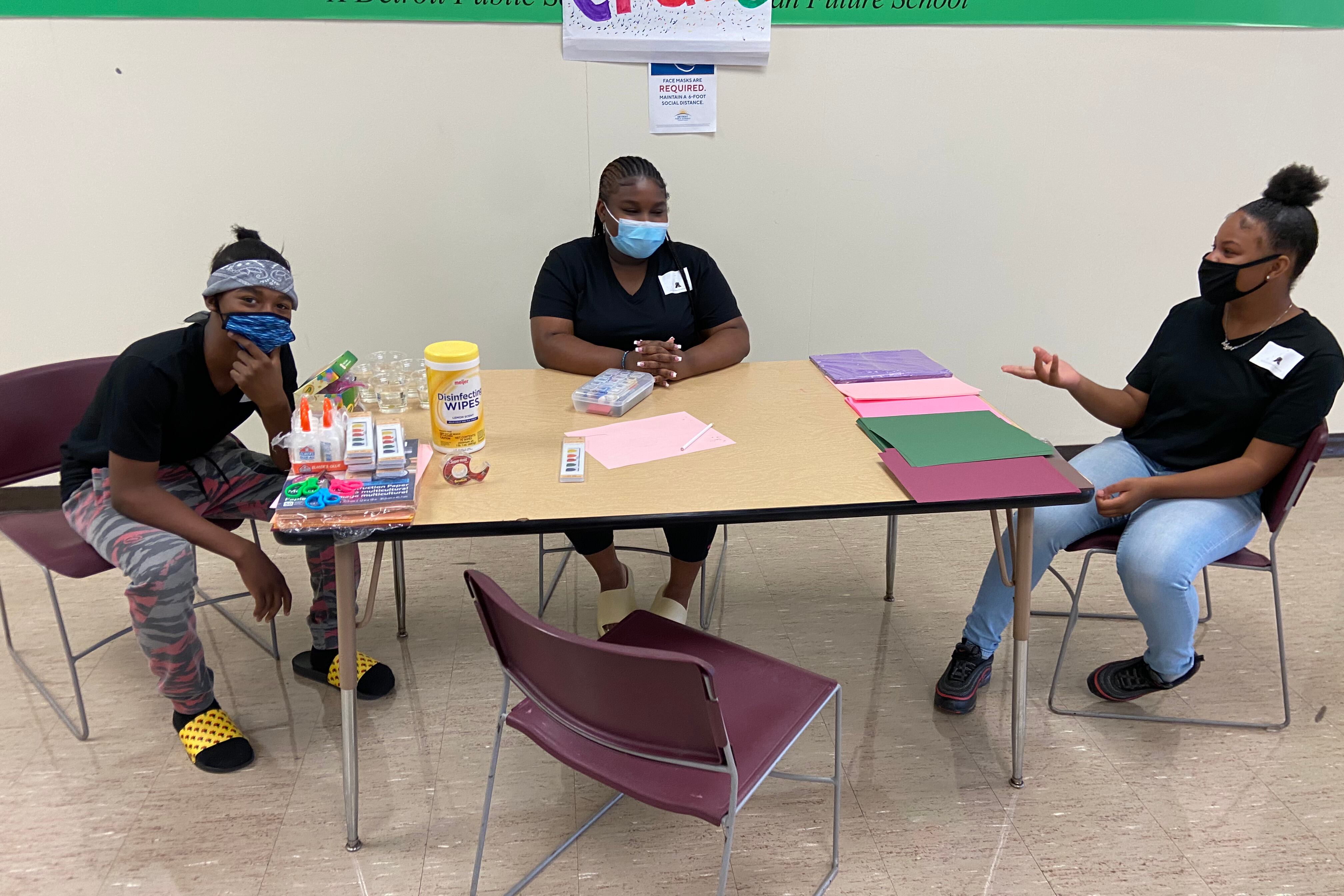

“One of the first things our students talked about was having social anxiety,” said Marini Lee, who runs McLee Educational Consulting, who ran a district-funded summer enrichment program for high school students this summer. “This is a way to work back into being with each other again.”

That was true for Anderson, a youth leader at a summer enrichment program run by the Coleman A. Young Foundation. The program is usually held on Saturdays, but with the influx of COVID funds, the Detroit district paid for it to operate five days a week during the summer.

One afternoon in July, Anderson sat with her friends in an air-conditioned DPSCD cafeteria, listening to a lesson on mindful breathing and yoga.

The exercises felt good. So did the hours she’d spent hanging out with her friends from the program, some of whom she hadn’t seen since before the pandemic.

COVID concerns kept her from seeing her cousin, Dominique Ross. Normally they’re close, seeing each other almost every week as leaders in the CAYF enrichment program.

They spoke proudly about their rise from students in the program to student leaders who help orient others to the program and run activities. But they were clear-eyed about the challenges they face this year.

“I’m going to be honest, sometimes I got so fed up with Zoom I just clicked off,” said Ross, a 10th grader at Bradford Academy in Southfield.

Nevyah nodded, adding that overwhelmed teachers sometimes ended classes early.

Even so, Dominique worries that in-person instruction will be tough for students no longer accustomed to classrooms. “As far as rules and expectations go, it’s going to take a while for [teachers] to get the students under control,” she said.

Both said they’d promised their parents to study extra hard this year. Nevyah, in particular, is entering her junior year — a pivotal one for college applications — with hopes of winning scholarships.

“I’ve still gotta accomplish my goals, I’ve still gotta get to where I want to go in life,” she said. “I think I’ll be learning things next year that I should have learned in virtual school. But I’ll learn it quickly.”