A turnaround program had been helping Michigan’s lowest performing schools improve but those gains stagnated during the pandemic, according to a new report from Michigan State University.

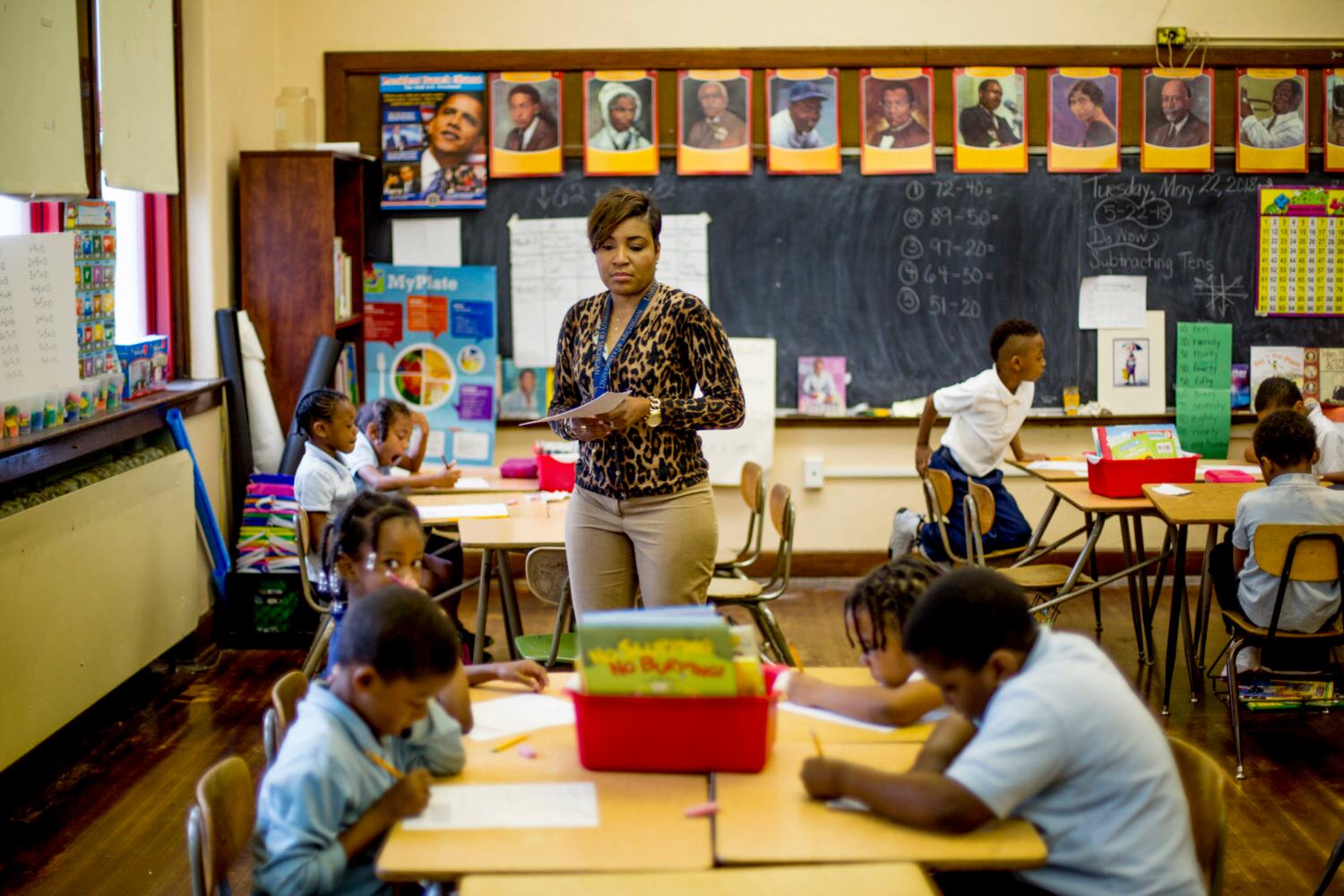

The pandemic “wreaked havoc” on these schools, known as partnership schools, even as educators and students made extraordinary efforts to continue teaching and learning, said researchers from the university’s Education Policy Innovation Collaborative.

The EPIC study found:

- On-time graduation rates, which had been increasing before the pandemic, decreased last year.

- Drop-out rates increased, but the number of students transferring to other schools decreased.

- Attendance lagged and students were less motivated to learn, but educators said they had a better rapport with those who showed up for virtual classes.

- Parent engagement decreased.

- More educators — especially novice and Black teachers — left the profession during the pandemic. But those who remained were more likely to stay rather than transfer to other schools or roles. They cited school leadership, culture, and climate as their reasons for wanting to stay.

The backslide doesn’t surprise researchers who were tasked with tracking the schools’ progress since 2017, when the Michigan Department of Education gave them more resources and a chance to improve rather than face closure.

Partnership schools had been making gains in elementary math and English before the pandemic, according to EPIC’s 2020 report.

The new report shows that partnership schools were more likely to offer remote-only instruction than higher achieving districts last year. Learning from home was especially challenging for these students because they also were more likely to experience economic instability, food insecurity, illness, and difficulty accessing health care. Researchers found they also lacked resources for at-home schooling such as internet access, desks, quiet workspace, parental help with school work, and transportation to get supplies.

“I think for the population we serve here that they do better in the building,” one charter school leader told researchers. “We struggle and we continue to struggle with the virtual model.”

Households were loud and chaotic, one teacher said.

“There were children running around screaming, dogs barking and television blasting. All this took the attention away from the lessons. At times, it was the opposite, with the parent sitting out of view of the camera whispering all of the answers,” the teacher said. “Either way, my students were not learning a thing.”

Still, teachers in partnership schools were undeterred. They were less likely to leave their jobs for other schools than colleagues in similar buildings not in the partnership program.

“What impressed me the most was these teachers didn’t just give up. They were really still trying, and they were reporting back that their school culture and climate were improving and their job satisfaction was improving,” said Katharine Strunk, director of the EPIC and a professor of education policy at Michigan State.

The state has identified 123 schools for the partnership program, including 50 in Detroit.

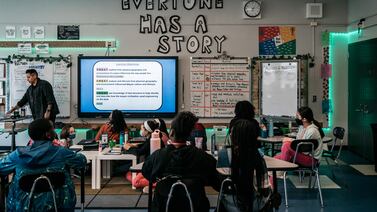

The report bolstered the state education department’s commitment to the program and its efforts to speed up learning by prioritizing the most crucial content over the next school year. The department expects to add more schools to the partnership program next fall.

“Many of the challenges faced by partnership districts are large systemic issues that span beyond the education realm, so any solutions require partners, time, and honest conversations about deep-seated changes that are necessary,” the department said in its written response to the report.

EPIC concluded that partnership schools would benefit from more funding, better recruiting and retention of faculty — especially Black teachers — and more robust socioemotional support.

The report is EPIC’s third on the effectiveness of the partnership program. Researchers said it was hard to isolate the effects of the program from the effects of the pandemic, which were more profound in communities of color and low-income neighborhoods that partnership schools tend to serve.

Researchers considered dropout rates, teacher mobility, district revenue data, educator surveys, and interviews. They used teacher perceptions of student learning rather than test results because the Michigan Student Test of Educational Progress, known as M-STEP, was not administered in 2019. Teachers estimated that 15% to 16% of students began the school year on track in language arts, math, science and social studies, and even fewer — 11% to 13% — finished on track.

They found the pandemic exacerbated already difficult challenges children in these schools faced.

“For many of our students, making it through the day is all they can do,” one teacher told researchers. “My high school students have shouldered enormous burdens this year. They are breadwinners, babysitters, tutors, cooks, and whatever else is needed in the household.”

Read the full report here.