Tripling the number of school literacy coaches. Closing the school funding gap. Creating a college scholarship program for education majors.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer counts these among her accomplishments in education. But the incumbent Democrat has more she wants to do if she is reelected.

That includes checking things off her first-term to-do list that got derailed by the pandemic or the Republican-controlled Legislature. It also includes dealing with the effects of the pandemic, such as academic and mental-health setbacks from extended periods of online instruction, and teacher burnout that has led to shortages in districts across the state.

In many ways, Whitmer’s record has been defined by her response to the pandemic. In March 2020, within days of the first confirmed COVID case in the state, she ordered all K-12 public schools closed as a health precaution, and went on to exercise broad emergency powers until the courts and the Legislature reined her in.

The following school year, while other governors pushed for schools to reopen classrooms and get back to normal — some went so far as to ban districts from requiring face masks and threaten to withhold funding — Whitmer remained a prominent advocate of keeping COVID prevention steps in place.

That record has drawn attacks from Republican challenger Tudor Dixon, who has accused Whitmer of “robbing students of their education” by ordering schools closed in 2020 and letting local school officials decide whether and when to resume in-person instruction.

Some of those closures persisted well into 2021, dealing a blow to student learning and mental health.

Whitmer says that helping them on both fronts is a priority heading into 2023. And she has taken advantage of Michigan’s strong economic recovery and federal relief funds to spearhead — in tandem with Republican leaders in the Legislature — unprecedented investment in education and mental health resources for children.

“We’ve got to do everything for our kids to ensure that there are better outcomes for our kids academically,” she said.

More money in school aid budget

Whitmer, 51, was a longtime state legislator from East Lansing before she was elected governor in 2018. Her mother and grandmother were teachers. Her grandfather was superintendent of the Pontiac School District. Both she and her children attended Michigan public schools.

“That’s why the work I’ve done has been centered around public education — protecting it and making greater investment,” she said.

On her watch, and following negotiations with the GOP-controlled legislature, the state’s school aid budget has grown from $14.8 billion to $19 billion, with a big boost in the latest budget for special education, mental health services, and teacher retention programs.

Meanwhile, she stymied efforts by conservatives to steer public dollars toward private schools, vetoing a voucher-like program for reading scholarships.

Going forward, Whitmer said she wants to provide a tutor for every child and create individualized learning plans.

Yet Michigan under Whitmer was slower to propose a comprehensive tutoring plan than other states that had big academic losses from the pandemic. While many other states were investing federal COVID relief money in statewide tutoring programs, and Michigan voters identified tutoring as a top priority, Whitmer didn’t make it a key part of her initial plan for the federal money. Months later, she proposed a $280 million tutoring plan, but only $52 million made it into the state school aid budget.

Whitmer’s campaign didn’t explain why she didn’t embrace tutoring sooner.

Spokeswoman Maeve Coyle noted that Whitmer has made historic investments in education resources, including stronger individualized instruction and more reading coaches. Those coaches are specially trained to help classroom teachers improve reading methods. The $24 million Whitmer negotiated into the school aid budget was enough to increase the number of coaches from 92 to 279 across the state.

Whitmer also increased the state’s investment in school-based mental health services to help students recovering from trauma so they are ready to learn. She wants to do more next year if reelected.

Teacher retention is a priority

A second term would mean a second chance to persuade the Legislature to provide retention bonuses for teachers and to pilot a home-based version of the Great Start Readiness preschool program — two of her priorities that Republicans shot down in budget negotiations. Democrats are hoping to not only beat Dixon, but also strengthen Whitmer’s hand by winning control of the Legislature.

Whitmer has portrayed Dixon as an agent of Betsy DeVos, the Trump administration education secretary and longtime proponent of private-school vouchers and other initiatives that would steer taxpayer dollars to private schools to promote school choice.

DeVos — who helped bankroll a campaign for a ballot initiative to allow people to claim tax credits for contributions to scholarship accounts for private schools and education services — was a major financial backer of Dixon’s campaign. .

“She and Betsy DeVos are arm-in-arm, and this is DeVos’ agenda to starve public schools of resources, to divert them to for-profit charters or parochial schools,” Whitmer said in a recent interview. “This is a dangerous strategy for Michigan and it will leave a lot of kids behind.”

Education advocates project the plan could reduce tax revenue by as much as $500 million.

“That would be devastating, and that’s why I think that public education is very much on this ballot,” Whitmer said.

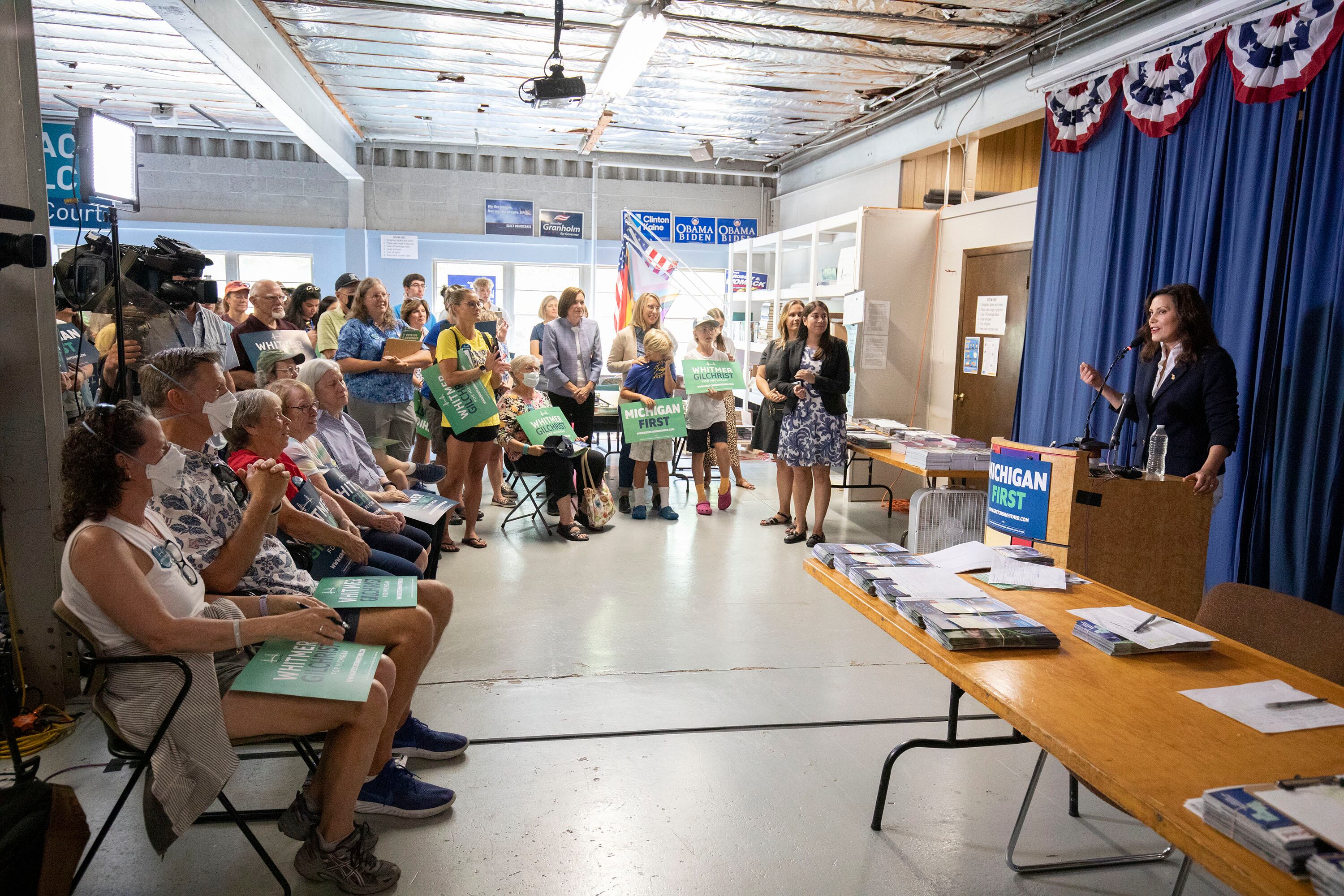

Supporters at a recent campaign rally in Trenton, downriver from Detroit, said they appreciate Whitmer’s focus on teacher recruitment and retention at a time of worsening staff shortages and declining interest in teacher preparation programs.

“She’s being very intentional about empowering teachers and getting them what they need,” said Velma Jean Overman, 67, of Inkster, who attended the rally with her 6-year-old granddaughter.

Whitmer’s four-year plan to offer teachers annual retention bonuses of up to $4,000 was another casualty of battles with the Legislature, but it will likely be back on the table if she is reelected.

“If we ask people to go into this critical work, they’ve got to be able to make a good living, and be treated with respect, and have the support to be successful,” Whitmer said.

She said she hopes that in November, voters will elect moderate senators and representatives who will be more receptive to retention bonuses and her other education initiatives.

“We can’t look at one another as the enemy,” she said. “We’ve got to be partners. When we’re successful in public education, it helps every child no matter what household they live in or what the politics of the community are.”

Tracie Mauriello covers state education policy for Chalkbeat Detroit and Bridge Michigan. Reach her at tmauriello@chalkbeat.org.