Tudor Dixon worked to make the election about parents’ rights and school choice, but in the end, Michigan voters chose Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, who ran on her record rather than an ambitious education plan for sweeping change.

The incumbent Democrat touted her accomplishments, including closing the school funding gap and tripling the number of school literacy coaches, but she faced criticism over decisions she made in 2020 around pandemic-related school closures and mask mandates.

When the Associated Press called the race for Whitmer at 1:20 a.m. Wednesday, she was leading with nearly 52% of the vote.

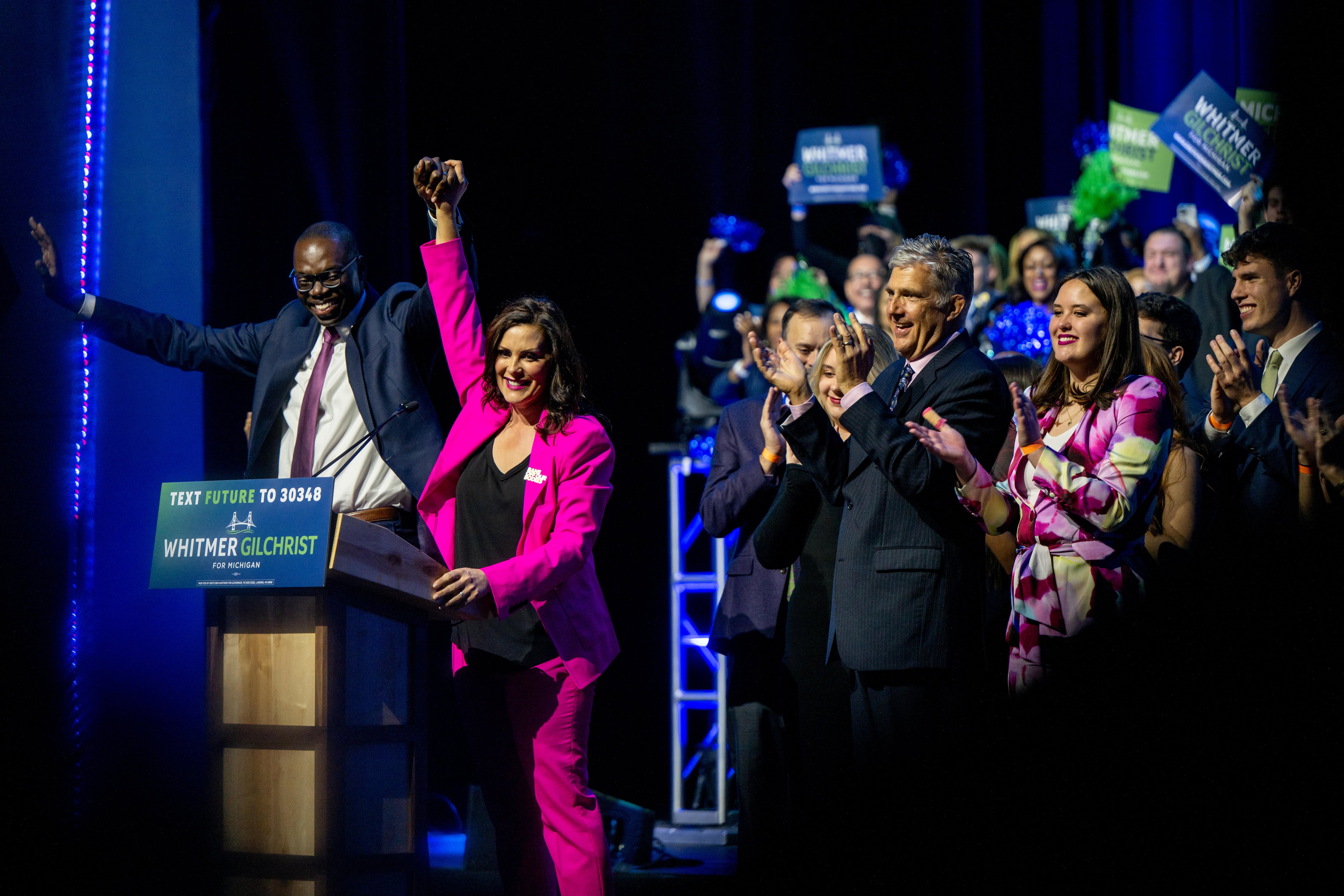

Later in the morning, Whitmer said “Michigan’s future is bright and we are about to step on the accelerator,” during a speech to supporters and media.

Whitmer said that over the next four years, she wants to build a Michigan “where every person is treated with dignity, can enjoy their personal freedoms, and chart their own path toward prosperity. I promise to be a governor for all of Michigan. I promise to work with anyone who wants to get things done and compete and win against anyone. We’re going to move this state forward. And I am excited about the work we will continue to do together.”

Jenna Bednar, professor of political science and public policy at the University of Michigan, said that though there was frustration during the pandemic, “voters appreciated how hard she worked to increase the funding available for public schools.”

“She didn’t run on a major transformation of the education system” like Dixon did, Bednar said. “She didn’t run saying we need to revamp the curriculum, or ban books, or keep certain ideas out of the classroom. Voters responded to that. They said, ‘Yeah, we don’t need to go there.’”

Whitmer’s win is evidence that voters want a more traditional set of education policies and platforms, said Sarah Reckhow, associate professor of political science at Michigan State University.

Throughout the campaign, Whitmer and Dixon offered vastly differing views on school safety, private school choice, curriculum, Michigan’s third-grade reading retention law, and more.

Reckhow said it’s possible that Dixon’s plan for private school choice didn’t resonate with voters because they have been satisfied with their local public schools even through the pandemic.

She also noted that Whitmer’s campaign focused on traditional Democratic educational values such as increasing school funding and providing more early childhood programs.

A second term gives Whitmer, 51, another chance to advance her agenda of paying teachers retention bonuses and piloting a home-based version of the Great Start Readiness preschool program. She included those items in her 2022-23 school aid budget proposal but was unable to get them through the Republican-controlled Legislature.

She now has the ability to push through these priorities, and others, now that Democrats gained control of both the Michigan House and Senate. It’s the first time in 40 years Democrats will control the governor’s office and the Legislature, according to Bridge Michigan. Their successes are due in part to redistricting.

A Democratic Legislature would mean support for even more school funding, particularly for the neediest districts, said Michael Montgomery, a political scientist and consultant who was chief analyst on the 1989-91 Citizens Education Committee to Improve Public Education in Detroit.

“Mostly, I think she’ll stay the course, making more progress if she has a Democratic Legislature and not making progress with a Republican Legislature,” Montgomery said. “She’s going to keep working.”

Tracie Mauriello covers education policy for Chalkbeat Detroit and Bridge Michigan. Reach her at tmauriello@chalkbeat.org.