Courses in Python, HTML, and SQL soon could replace Spanish, French, and German on Michigan high school students’ schedules.

Students who study computer programming languages or take other coding courses would get credit toward their world-language graduation requirement under a bill working its way through the state Legislature.

Supporters say it would give students greater flexibility to explore a skill that could help prepare them for future jobs.

Nate Henschel, director of government affairs for the Grand Rapids Chamber, said he hopes giving students a coding option will spark interest in the science, technology, engineering, math fields and potentially lead to high paying jobs.

“It’s what the economy needs,” he said. “We’re seeing a growing demand for jobs in this field. It just gives kids the option.”

Separate legislation also could chip away at the state’s language requirement. It would require high school students to take a half-credit financial literacy course. Credit for that course could be used toward fulfilling world language, math, or art requirements.

Both bills have support from business groups that say they’re interested in a better skilled workforce. But in an example of the ongoing STEM-versus-humanities debate in education, they’re running into resistance from critics who worry that the bills will reduce local flexibility over curriculum and further crowd out cultural understanding in favor of more technical education.

“Personal finance has nothing to do with world language,” said Julie Foss, public liaison for the Michigan World Language Association, which opposes the bills on coding and personal finance. “It’s not that we think that either of those things isn’t valuable, but they have no place replacing world languages.”

She said if Michigan determines that students need to learn computer coding, it makes more sense for the course to fulfill a math or science requirement.

Michigan students already can opt out of one of their two required foreign language credits if they take a career and technical education class or if they earn more than two visual and performing arts credits. It’s unclear how many students use CTE or arts classes to fulfill the world language requirement, but 103,000 students were enrolled in career and technical education programs last school year.

Students also can fulfill world language requirements before high school. For example, a district could offer a K-8 language program for all children that results in proficiency equivalent to two years of high school course work.

The Michigan Association of Secondary School Principals supports financial literacy but opposes the bill because it doesn’t give districts enough flexibility to decide how to deliver instruction. For example, districts should have the option to embed financial literacy content into existing courses, MASSP lobbyist Bob Kefgen said.

The Michigan Department of Education opposes both bills. Legislative liaison Sheryl Kennedy said the department supports the teaching of coding and financial literacy but opposes any bill that substitutes credit from one area of the Michigan Merit Curriculum for another.

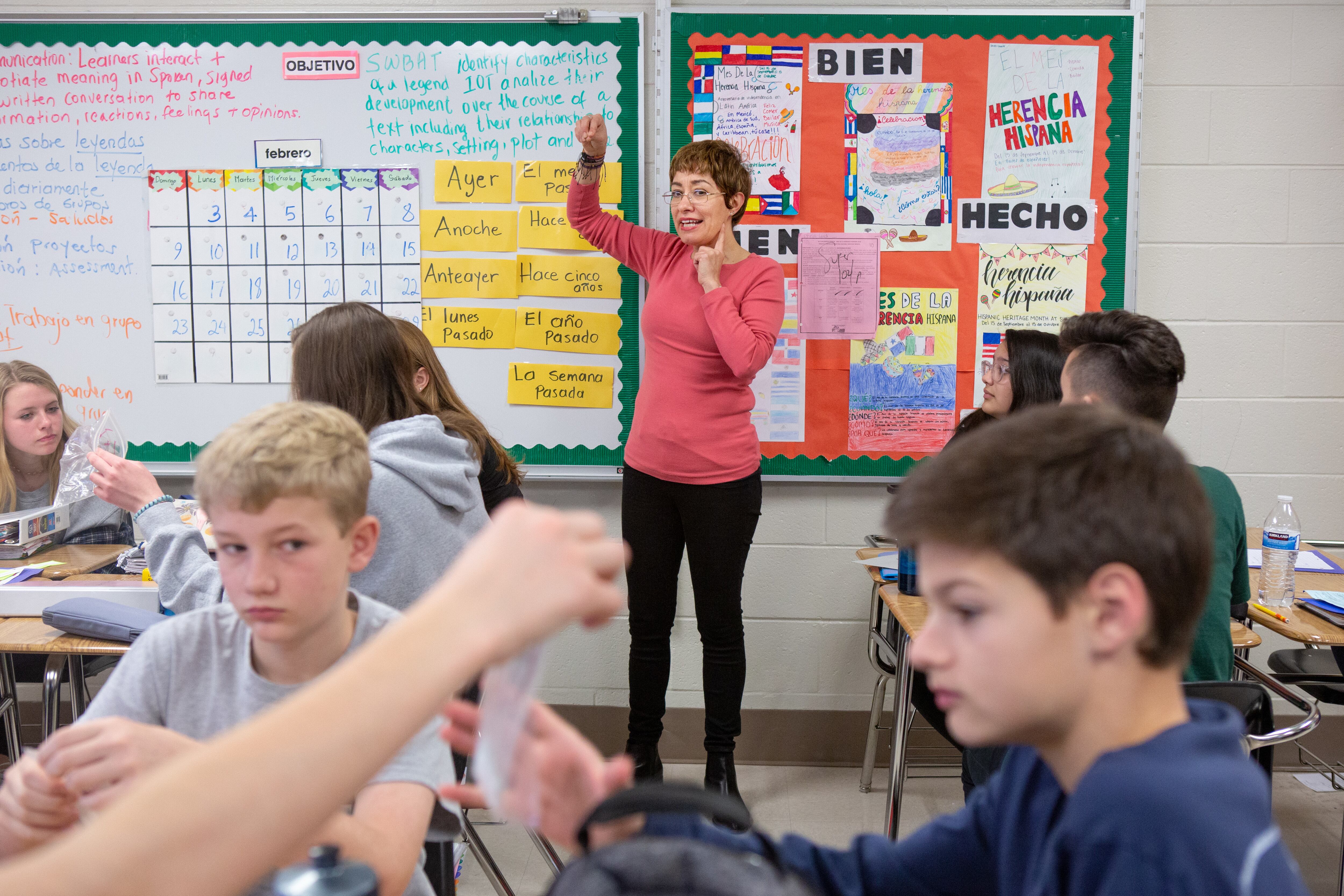

“Foreign language isn’t just about learning to speak the language,” she said. “It is learning about a culture different from ours. Coding does not do that.”

Foss, who also is a French professor, said people often think of world language courses as having a lot of memorization of vocabulary and grammar rules. But these courses have an “immersive environment” where “culture is at the center,” she said, and students learn communication skills that employers are looking for.

Others say coding is a communication skill, too, and that programming languages are as important as spoken ones.

The Grand Rapids Chamber supports both bills and has been working on the computer coding component for years, according to Henschel.

On the personal finance bill, Henschel said “so many young adults are unprepared when it comes to reviewing loans, credit cards, and other significant financial decisions” and that the bill will hopefully lead to “better financial well-being for years to come.”

Some students are already taking financial literacy courses.

In Grand Rapids, Forest Hills High School’s personal finance course is a popular elective. Students say it teaches them how to budget money from their minimum-wage jobs, understand pay stubs, open savings accounts, and invest in stocks.

“It’s one of the only classes in school where I can truly see how it will help me in the future,” junior Clare Hilary testified last week before the Senate Committee on Education and Career Readiness.

Classmate Jacquelinn Festian told senators she didn’t know the difference between a debit card and a credit card before she started the class. Now she knows “it’s super easy to go into debt with your credit card.”

She said every student in Michigan should have the chance to learn that and other financial lessons before they graduate.

Both measures could be voted on by the full Senate in the coming days or weeks. Both were previously approved by the House. The Senate Committee on Education and Career Readiness made small technical changes to the bills, so the House would have to vote again if the Senate approves the amended bills.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has not said whether she would sign the bills if they reach her desk. She will review the bills as they move through the legislative process, spokesman Bobby Leddy said Wednesday.

Sixteen years ago, Michigan had only one statewide graduation requirement for high schools: that students take one civics course. Otherwise, districts were free to set their own requirements.

In 2006 the state adopted the Michigan Merit Curriculum, which mandates a minimum of 18 credits in specified subjects. Local school districts can add to those requirements, and many do.

Ten Michigan districts require personal finance courses, according to NextGen Personal Finance, a nonprofit advocacy group pushing states to require them for all students. Banks and credit unions across the country also have been working to draw attention to the need for financial literacy.

Their efforts have been successful in Florida, Nebraska, Ohio, and Rhode Island, which recently passed laws requiring high school students to take personal finance courses. Including Michigan, 18 other states are considering similar laws.

Tracie Mauriello covers state education policy for Chalkbeat Detroit and Bridge Michigan. Reach her at tmauriello@chalkbeat.org.

Isabel Lohman covers education for Bridge Michigan. Reach her at ilohman@bridgemi.com.