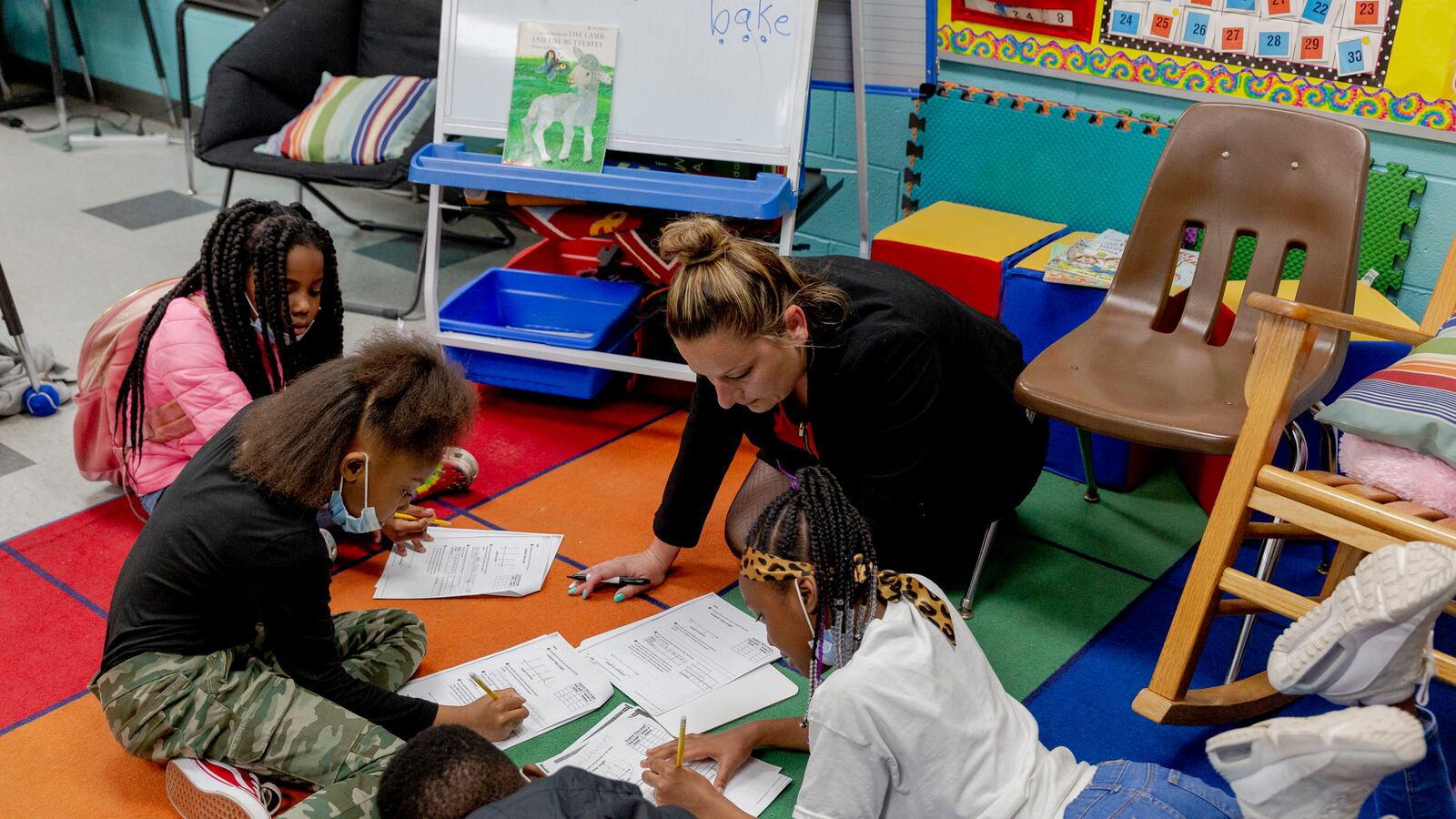

The lightbulb went on for Cahni James as she sat on a brightly colored rug with a tutor and three other third graders at her school in Ecorse, a city just outside Detroit.

“Ooh, I get it,” she said, after an explanation about units of measure.

“When I’m alone with my teacher, I can concentrate,” she explained later, noting that she finally understands fractions thanks to after-school tutoring sessions.

Scenes like this one were widely envisioned when the federal government sent an unprecedented $190 billion to schools nationwide to help students recover from the academic and emotional effects of the pandemic. Tutoring is among the most powerful learning accelerators that have ever been studied in depth, experts say. Top policymakers, from President Joe Biden on down, named tutoring as a key piece of the post-COVID comeback for American schools and encouraged schools to spend COVID funds on tutoring programs.

Michigan could use such a potent catch-up tool. A quarter of K-8 students tested made no academic growth between fall 2020 and fall 2021. Experts warn that unremediated learning delays could eventually translate into lost wages and lower educational attainment. A January poll found that Michigan voters considered tutoring to be their top priority for federal COVID dollars for education, which are known as ESSER funds, for Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief.

But tutoring has yet to emerge as a central feature of Michigan’s effort to use federal dollars to spur an educational comeback.

State leaders have not provided the coordination and financial support that have been central to tutoring expansions in other states, leaving individual school districts to develop their own programs or take other approaches to learning delays. At the same time, staffing challenges have crimped districts’ ability to start new initiatives.

The result is a small-scale, uneven patchwork of tutoring programs that falls far short of the broad effort that experts say would be needed to make a major dent in student learning loss statewide.

It remains to be seen if districts’ other efforts to help students catch up academically — such as reducing class sizes or expanding summer school — will be enough to reach all students statewide.

A few indicators of Michigan’s tepid commitment to tutoring:

- Only 223 of 818 Michigan districts mention tutoring in their ESSER spending proposals submitted in December. Districts may be spending federal dollars on activities that resemble tutoring but are called something else, or they may be using other funding sources, such as state dollars.

- Each state was allowed to keep up to 10% of its federal COVID education funds to spend on its own, without sending it to school districts. In Michigan, that amounts to $576.8 million. But Michigan is not dedicating any of that share to support tutoring, unlike at least 14 other states, including Illinois and Tennessee.

- Michigan hasn’t gone beyond providing technical guidance on tutoring. Meanwhile, 20 other states, including Indiana and Louisiana, are helping to recruit tutors or dedicating state funds to expand tutoring.

- Districts have proposed to spend at least $62 million of COVID funds on tutoring programs. That’s about 2% of the total spending proposed by districts as of December. Districts propose to spend another $71.5 million on academic interventionists, whose role is similar to tutors, though in some cases those teachers are already working at schools.

- Reporters interviewed, visited or surveyed 16 districts that plan to spend COVID funds on tutoring and found that most are missing at least some best practices that would ensure the effectiveness of their programs.

“Michigan students’ educational recovery needs strong state leadership,” said Jennifer Mrozowski, director of communications for Education Trust-Midwest, a nonprofit advocacy group that has called for an expansion of tutoring services. She called the reporters’ findings “very disappointing.”

Michigan leaders: Districts are responsible for COVID spending decisions

Decades of research clearly show that high-quality, small-group tutoring vaults students forward academically.

A 2021 paper said tutoring is “among the most effective education interventions ever to be subjected to rigorous evaluation” and laid out a blueprint for making tutoring a standard feature of public schools, noting that the multibillion-dollar private tutoring industry is already serving families who can afford it.

Biden took up the cause in his State of the Union address in March, saying “We can all play a part — sign up to be a tutor or a mentor.”

Michigan lawmakers have previously seen the value of tutoring, albeit on a smaller scale. The state’s third-grade reading law includes a range of measures to boost literacy among young readers, including small group or 1-on-1 instruction — tutoring — for students who need extra help.

And many districts confronting learning loss from the pandemic are starting new tutoring programs or expanding existing ones. Detroit Public Schools Community District, for instance, has multiple vendors providing tutoring that meets most of the best practices recommended by experts.

But while some states used their 10% shares of federal COVID school funds to hire and train tutors, Michigan lawmakers sent most of that money to districts in wealthier areas that were set to receive the least federal COVID dollars. That money hasn’t been spent yet as the wealthy districts struggle to comply with requirements that the money must be used exclusively to support students who were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.

Why didn’t state officials seize on tutoring as a top educational priority? State officials don’t provide a clear answer.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer signed off on the plan to send state funds to wealthier districts. Her office did not return a request for comment.

Rep. Pamela Hornberger, a Republican and the chair of the House Education Committee, said legislators weren’t aware of the rules attached to the federal COVID funds. Asked whether direct support for tutoring would have been a better use of the funds, she said “it may have been a better plan, but we don’t have an education department that is at all creative.”

“A lot of it falls back on the districts,” she added. “Districts have more money than they’ve ever had, and we’re hoping that they’re spending those on learning loss.”

William DiSessa, a spokesman for the Michigan Department of Education, pointed out that the Legislature, not the department, was responsible for allocating the state’s share of the funds.

He noted, too, that 90% of the federal funds went directly to school districts, some of which created tutoring programs.

“As Michigan is a local-control education state, local decisions on the use of funds should align with local situations and governance,” DiSessa said in an email.

MDE directed reporters to a U.S. Department of Education handbook that addresses tutoring as one of the ways for students to recover. DiSessa said MDE shared this resource in webinars and presentations. MDE also created a list of best practices for tutoring but stopped short of advocating that districts use federal funds to create tutoring programs.

He did not provide additional examples of MDE advocating that districts spend their money on tutoring programs, nor did he directly respond to Hornberger’s comment about MDE lacking creativity.

Lou Glazer, president of Michigan Future, a nonpartisan education think tank, cautioned that tutoring is just one way to address learning loss.

“If some districts looked at tutoring and decided to take another approach to learning loss, I wouldn’t want to penalize them for that,” he said. “The districts that should be criticized are the ones that took the money and didn’t do anything to make up for lost time.”

A tutoring patchwork

At least a dozen states and many large city districts have created large-scale tutoring efforts over the last year and a half, often investing significant shares of their federal funds. Tennessee is spending $200 million to hire and train tutors and provide matching grants to districts. New Mexico plans to spend $62 million to train tutors and support districts in developing programs. Louisiana used COVID funds to create an extensive series of educator trainings and technical guidance on tutoring.

In Michigan, in the absence of a statewide plan, many school districts haven’t indicated any plan to offer tutoring, instead opting for other academic catch-up programs such as expanding summer schools.

Of the 818 districts that had submitted COVID spending proposals in December, 223 districts mentioned the word “tutor.” Those line items totaled $62 million, or about 2% of the proposed spending reviewed by reporters.

To be sure, districts didn’t always call tutoring-like activities “tutoring.” For instance, districts proposed to spend at least another $71.5 million on academic interventionists — teachers trained to work in small groups with students who have fallen behind.

But the interventionists mentioned in many districts’ spending proposals were already employed by those districts doing the same work. Under federal rules, districts can use COVID funds to support activities they were already doing.

Indeed, available data shows a tutoring expansion only in some pockets of the state, experts and educators in Michigan said.

Kevin Polston, superintendent of Kentwood Public Schools near Grand Rapids, said hiring difficulties and burnout among current staff, plus COVID-related disruptions during this school year, have made it difficult to mobilize a large-scale tutoring effort.

Polston was appointed by Whitmer to lead a panel that recommended high-dosage tutoring as a key component of a blueprint for Michigan’s learning recovery.

“We have unprecedented funds and unprecedented need, but we often can’t get the staffing to provide that level of support,” he said of tutoring. He called on the federal government to extend spending deadlines for COVID funding, which he said would give districts more time to make hires and start new programs.

The $6 billion in federal funds came in three rounds. The first round of money came from the CARES Act, which was passed in March 2020, during the Trump administration. Plans for that money must be set in stone — if it hasn’t already been spent — by this September. The CRRSA Act was passed in December 2020 and the money must be committed by Sept. 30, 2023. The latest round of funding comes from the American Rescue Plan which must be committed by Sept. 30, 2024.

“Recovery is not going to happen in a school year,” Polston said.

Student recovery may have gotten a boost in schools that have used federal dollars to mount tutoring efforts. But even there, it is not clear that the programs will live up to the promise of high-quality tutoring.

As part of a COVID reporting collaborative between Chalkbeat Detroit, Bridge Michigan and The Detroit Free Press, reporters visited, surveyed, or interviewed 16 districts across the state that are using federal COVID dollars to run tutoring programs.

They found that many districts weren’t able to hit the benchmarks for high-quality tutoring laid out by educators and researchers, limited by issues with staffing and transportation.

Staffing problems limited the scope of tutoring at Oakview Elementary School in Muskegon, where 97% of students come from low-income homes. A federally funded program includes four classroom teachers who get paid a stipend to stay after school to each help a small group of their students recover.

Principal Brian Gamm said that ideally, the program would reach more students, but “we’re asking the same people to do the work.”

School ends for students at 2:12 p.m., but teachers cannot begin tutoring until they have completed their typical day, which includes an hour of planning time at day’s end for regular classroom lessons. So students work independently for an hour while the teacher supervises them during their planning period. Then tutoring begins at 3:15 p.m.

In one tutoring session led by a classroom teacher, seven second-grade students practice math skills in Carla Moffett’s room. According to best practices, tutoring would have no more than four students per tutor.

Moffett, a second-grade teacher, said that it would help if she could focus on, say, only two students, but that there are many students who “need an extra push.”

She said she believes most teachers want to be directly involved with catching their students up, but some teachers have other obligations after school or just don’t have the capacity to teach more because “burnout is real.”

The school has four other after school intervention programs using other sources of funding. One option is a four-week pilot program where building substitutes supervise students learning math with an online tutor. Gamm hopes that if the program proves to be successful, more students can get the help they need without an additional burden on classroom teachers.

The effort underscores the imbalances schools have been struggling with since even before the pandemic.

“The last few years because of COVID, educational systems were totally different,” principal Gamm said. “And now we’re reinventing what we are.

“We don’t want to go back to the way things were because things weren’t always working well for our kids,” Gamm added. “So we’re trying to come up with new and innovative ways, things that we tried to learn from COVID, but it’s just very, very challenging to do. And again, we’re asking the same people … who are in it to be creative and think differently. That’s hard to do.”

Koby Levin is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering K-12 schools and early childhood education. Contact Koby at klevin@chalkbeat.org.

Isabel Lohman is an education reporter for Bridge Michigan. Contact Isabel at ilohman@bridgemi.com.