The federal COVID relief aid flowing into Michigan schools to help students overcome two years of learning loss has helped some school districts climb their way out of financial trouble.

Eight years ago, 55 Michigan school districts operated under some form of state oversight because they ran operating deficits, spending more than they received in revenue. By the end of the 2020-21 school year, after the first batch of federal COVID aid arrived, that number was down to just a handful.

A review of districts that have faced the longest-running fiscal shortfalls showed that several of them used their federal COVID relief aid, known as ESSER funds, to cover basic operating costs, such as staff salaries and supplies, and reallocated their general fund dollars to shore up their reserves and eliminate deficits. The review is part of an ongoing effort by Chalkbeat Detroit, Bridge Michigan and the Detroit Free Press to track the impacts of an unprecedented infusion of federal funds into Michigan schools.

Take, for example, the Benton Harbor district, which the state had threatened to shut down in 2019 because of persistent deficits and academic struggles. The district had shuttered its library and staffed nearly half of its classrooms with underqualified long-term substitutes, but it still struggled to eliminate its deficit as enrollment fell. In recent years, fewer than 10% of district seniors met college readiness benchmarks in reading and math.

But with the help of federal aid, the district’s general fund balance went from a deficit of $3.7 million in 2018-19 to a surplus of $3.2 million in 2020-21. And for the first time in nearly two decades, it’s no longer under state oversight.

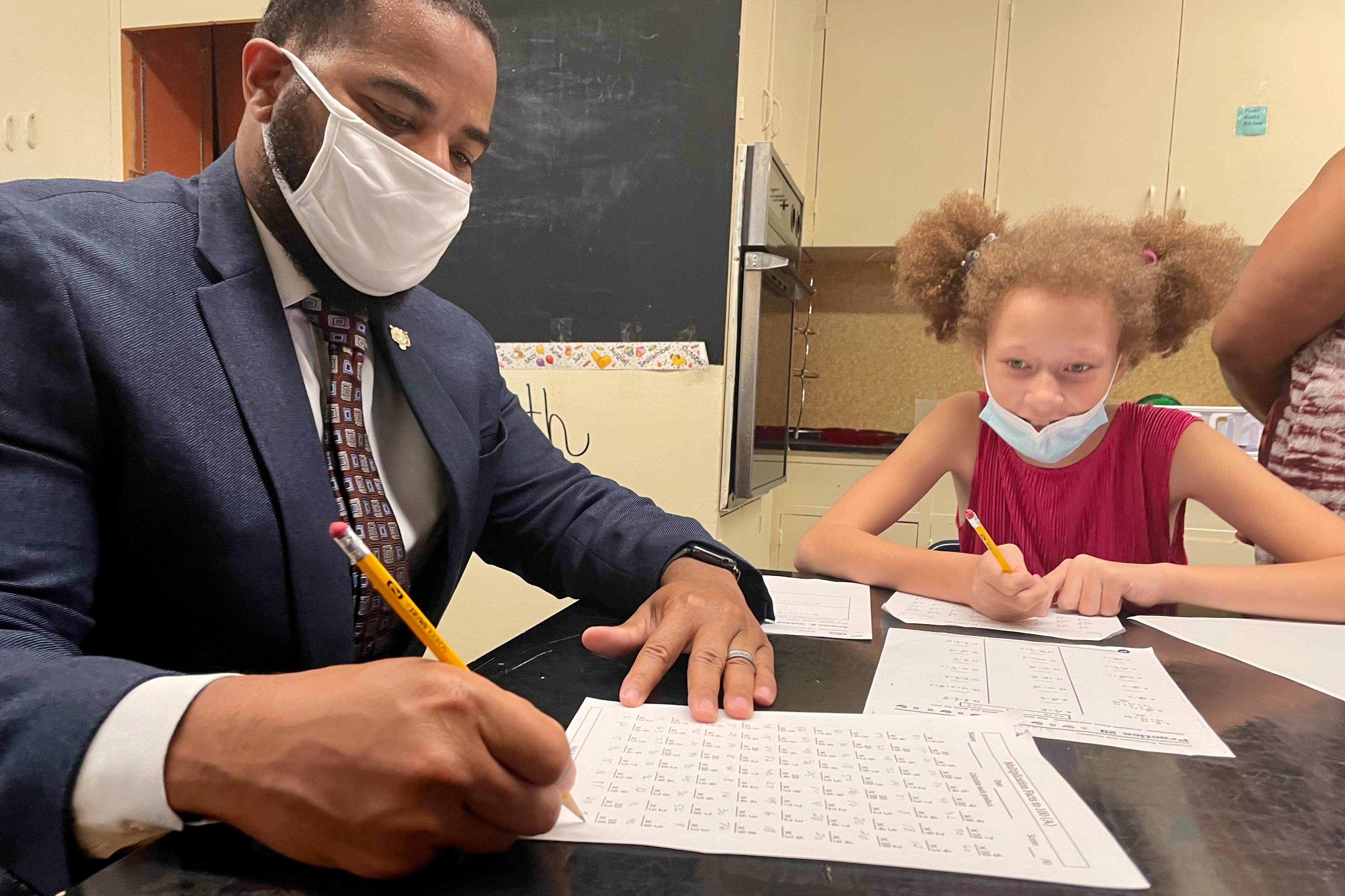

“It’s just good decision-making,” said Andraé Townsel, who was superintendent of Benton Harbor Area Schools until last month. “You were able to, by law, utilize those funds for some routine expenses.”

Suddenly free from an era of forced belt-tightening, Benton Harbor and other districts now find themselves in the same position families might be in when they pay off their credit card balances or student loans: pondering the possibilities. For school officials, the new financial freedom could bring an opportunity to refocus on neglected educational priorities, such as improving academics and teacher pay, or reviving depleted elective programs such as art and music.

At the same time, districts are under pressure to make sure the intended uses of the COVID aid, including tutoring and mental health support for students, aren’t shortchanged in the quest for balanced budgets — and that the balance can be sustained once the federal dollars run out.

Along with Benton Harbor, the Pontiac, Pinckney, Vanderbilt, and South Lake school districts — all of which had been under state oversight at some point in recent years — swung to a positive fund balance in the 2020-21 fiscal year. In addition, Flint Community Schools, which still had a deficit, got out of state oversight by using its $156 million in COVID relief to create a temporary reserve.

School fund balances grew statewide this year, suggesting that financially stable districts, too, have used COVID dollars to boost their reserves.

Why districts have an incentive to tackle deficits

Federal funds weren’t solely responsible for the improved finances, said Chad Urchike, a financial specialist at the Michigan Department of Education. Even before the pandemic, state education budget increases were helping more districts improve their financial health. Measures designed to reduce the financial impact of pandemic-related enrollment losses also helped.

But superintendents say last year’s federal aid provided enough breathing room for several perennially struggling districts to move into the black and clear a crucial hurdle: escaping state oversight.

After the Great Recession walloped the state’s economy more than a decade ago, Michigan moved aggressively to head off fiscal emergencies at the municipal level that threatened to leave the state on the hook for unpaid debts.

Laws passed since then have greatly expanded the state’s oversight of local school district finances, making it easier for the state to assume control of struggling districts, said Mike Addonizio, professor of education and finance at Wayne State University.

In 2015, “an early warning system” signed into law by then-Gov. Rick Snyder created a set of financial reporting requirements for school districts operating with a deficit, including the filing of a deficit elimination plan that satisfies the state Treasury Department. The legislation also gave the department more authority to recommend an emergency manager to take control of a district’s finances and operations.

The deficit elimination plans may require a district to make spending cuts such as building closures, staff reductions, and wage concessions — changes that risked contributing to enrollment declines. If a district failed to make enough changes, a state-appointed emergency manager might override the elected school board to impose cuts, as has happened in Detroit and Highland Park.

“When a district is trying to eliminate its deficit, they really have to take a hard look at those personnel expenditures, cuts to their academic program options, and think about things like band, art, foreign language, those electives,” Addonizio said.

Given that prospect, he said, using federal funds to stabilize budgets made sense for districts.

“School districts have an incentive now to eliminate budget deficits to basically keep the state off their backs, or out of their local affairs,” he said.

Crisis and opportunity

Pontiac School District spent five years under state oversight as it wrestled with a 2013 deficit of $52 million, brought on in part by a decline in enrollment and the collapse of the city’s tax base after the 2008 financial crisis.

Under a consent decree with the state that ended in 2018, the district froze teacher pay scales, sold vacant buildings, and restructured debt with the state and community banks, school board President Gill Garrett said.

Last year, Pontiac finished with a positive fund balance of $7.9 million, its first surplus in a decade. This year, it has grown to $9 million. Garrett said the use of federal pandemic-related relief money was “a contributing factor.”

Laura Parker, a parent in the district, said she backs the district’s decision to use federal funds to shore up its finances. She feels the district could do more to help students recover from the pandemic, such as extend summer school by a few weeks. But she says as the mother of five children, she knows what it’s like to struggle to pay bills.

“If I got a lot of money, I’d probably pay off my debts first,” she said.

When Rick Todd was hired in 2013 as superintendent of Pinckney Community Schools, the district had a nearly $2 million deficit.

Enrollment declines accelerated after the Great Recession, and the rolls have shrunk by more than half since then thanks to a low density of affordable housing and an aging population.

Pinckney fell into a deficit in 2012-13, and was required to submit a series of increasingly aggressive deficit elimination plans to state education officials and the Department of Treasury.

The year before the pandemic, the district had begun its deepest cuts yet, laying off 23 teachers, and was still at the risk of running a deficit. When the federal government began sending billions of dollars to schools to deal with the pandemic, Todd says, the district saw a chance to further stabilize its finances.

“Where some schools were giving large bonuses and stipends for extra work, we chose not to do that,” he said. “Whatever we could do to offset costs for our general budget, we took advantage of that.”

Pinckney used COVID relief funds to maintain and improve air filtration systems and purchase new technology and software — costs the district would have had to cover on its own if not for the federal aid. The district’s maintenance director became the director of COVID response, and his salary was paid using federal funds.

“The pandemic was looked upon as a very challenging thing for schools, and it was,” Todd said. “I knew from a financial standpoint we could use this as an opportunity.”

Better than a Band-Aid?

But the question remains: How long can these struggling districts keep their budgets balanced? Some observers worry that COVID relief funds only offer a temporary fix.

Federal spending guidelines don’t prevent districts from using the money to cover teacher salaries and other recurring costs. But if they do, some fear, they’ll find themselves scrambling again when the federal aid runs out in 2026. Indeed, when the first federal COVID dollars arrived in Michigan school coffers, experts began warning of a looming “fiscal cliff.”

“For certain distressed districts it’s very plausible that [federal aid] is just going to mask financial troubles temporarily,” said Randy Layman, a director for S&P Global Ratings who specializes in credit ratings for U.S. local governments, including school districts.

Many districts have responded to these concerns by focusing their COVID spending on one-time costs, such as upgrades to ventilation systems or temporary expansions of summer programming. As part of their deficit-reduction plans, some districts have also cut their operating costs through measures such as teacher layoffs.

And for urban districts, the COVID grants are so large — in Benton Harbor, it’s equivalent to roughly twice the district’s pre-pandemic yearly spending — that they could provide a financial cushion well beyond 2026 if managed conservatively.

Now that Benton Harbor is free from state oversight, it’s up to the district to protect its positive fund balance, said Angel Crayton, a school board member.

“It’s something to celebrate,” she said at a June meeting. “But it’s like being on the basketball court: We can’t celebrate and then allow the other team to score while we’re celebrating.”

Ethan Bakuli is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering Detroit Public Schools Community District. Contact Ethan at ebakuli@chalkbeat.org.

Koby Levin is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering K-12 schools and early childhood education. Contact Koby at klevin@chalkbeat.org.