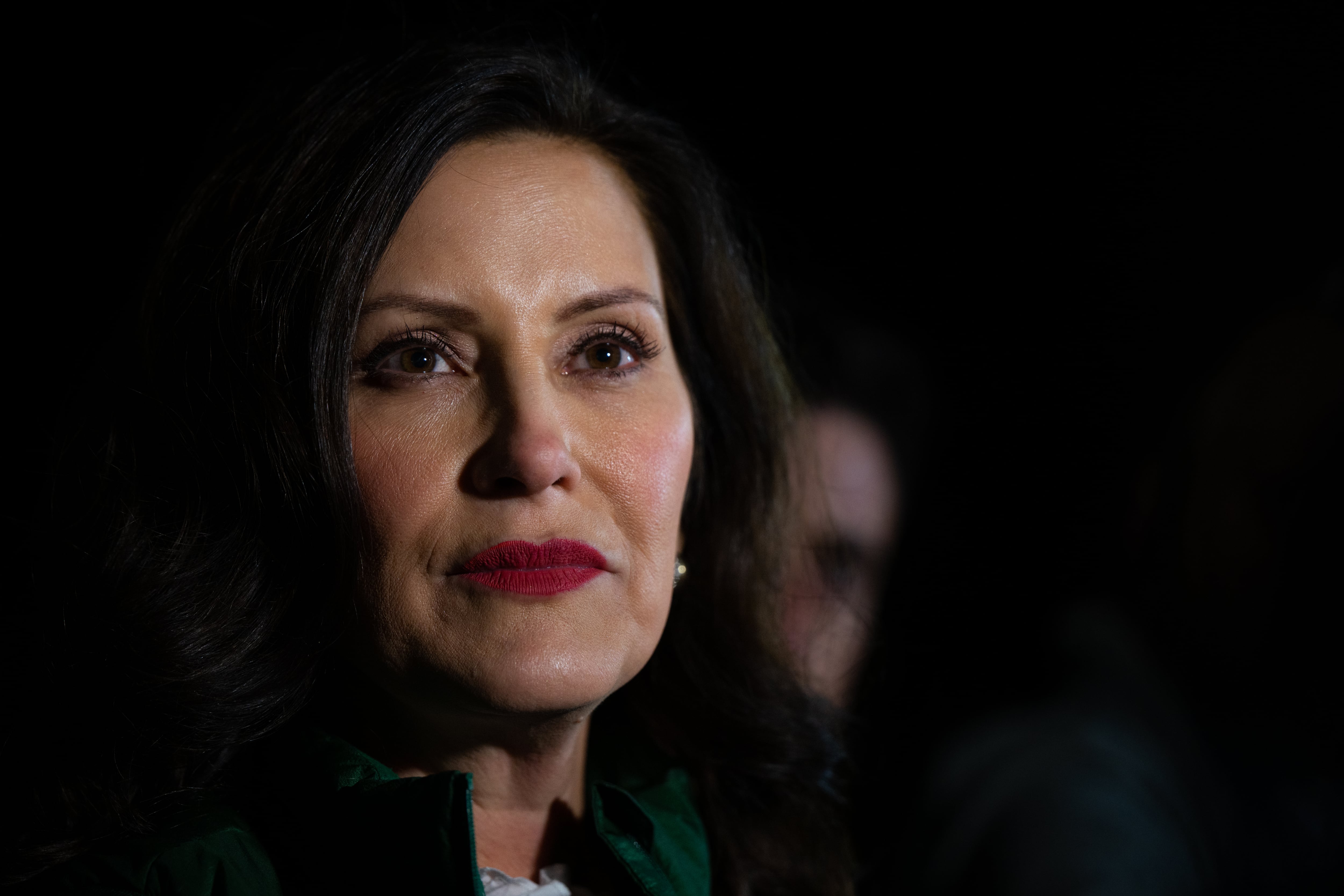

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, working with a friendly majority in the Legislature and a historically large budget surplus, used the first major speech of her second term to explain how she plans to use those advantages to shape Michigan’s education policy.

At the top of the wish list: providing free preschool for all Michigan 4-year-olds over the next four years and expanding one-on-one tutoring for older children.

“When a child gets a great start, and learns to read, and graduates high school … they are on track to land a good-paying job or pursue higher education,” the governor told a joint session of the Michigan Legislature in her State of the State address Wednesday. “Unfortunately, the last few years have disrupted regular learning patterns.”

In-class instruction alone isn’t enough for kids to catch up, Whitmer said.

It was the governor’s fifth State of the State speech, but the first delivered to a majority that shares her political ideology. Her first four were before Republican majorities that resisted her plans. Now the Democrats control both legislative chambers for the first time in 40 years.

That doesn’t mean her proposals will sail through without resistance. Republicans and school choice proponents already are pushing back.

Hours before the speech, the Great Lakes Education Project predicted that Whitmer’s plans would only spend more on an already broken system.

“Doubling down on the systems and bureaucracies that have already failed our kids won’t produce better results,” Executive Director Beth DeShone said in a written statement. GLEP is a nonprofit group founded by Betsy DeVos, a former U.S. education secretary and Michigan’s most vocal proponent of school choice.

DeShone said she prefers policies that give parents more control over their children’s education such as a program allowing tax credits for contributions to scholarships that parents could use for private school tuition, tutoring, or extracurricular activities.

DeShone and other Whitmer critics were quick to point out that test scores have been declining across Michigan, particularly in Detroit and other urban areas hit hardest by the pandemic.

Tutoring plan is broad in scope

Tutoring is at the center of Get MI Kids Back on Track, Whitmer’s plan to help struggling students rebound after two years of pandemic-related disruptions that set back learning.

Even if the Legislature agrees, it won’t be easy to staff the program. Already districts are having trouble finding enough tutors for existing local programs.

Whitmer did not say how much the program would cost. Those details will emerge later as she rolls out her 2024 budget over the coming weeks.

Whitmer proposed a similar tutoring plan last May, saying then that it would cost $280 million. The proposal came three weeks after Chalkbeat Detroit, Bridge Michigan, and the Detroit Free Press reported that Michigan wasn’t making the same kind of investments that other states had in the comprehensive statewide tutoring strategies that researchers say make a difference. Instead, Michigan districts have been left to develop their own tutoring programs to help children catch up after two years of pandemic-related disruptions.

Republicans, who then controlled the Legislature, largely dismissed her proposal but did provide $52 million for tutoring in this year’s school aid budget. Their own plan, a $155 million proposal to provide up to $1,000 per student for parents to hire private reading tutors for elementary children, was vetoed by Whitmer, as public school advocates said it would siphon money away from public schools.

Get MI Kids Back on Track is broader in scope than the GOP plan and would provide tutors for all grades and core subjects.

“Whether you’re a third grader learning about the solar system, a sixth grader focusing on fractions, or a junior sharpening persuasive writing skills, tutoring addresses your specific learning challenges,” Whitmer said in her speech.

Advocates from the K-12 Alliance of Michigan back the education priorities Whitmer outlined Wednesday.

“We know that providing students with one-on-one tutoring support is often one of the most important resources we can make available in our schools,” said Executive Director Bob McCann, whose group represents superintendents from Michigan’s most populous counties.

In his written statement, McCann added that universal pre-kindergarten will ensure that all families have access to programs to prepare their children for long term success in school.

Whitmer’s K-12 proposals aren’t new. She raised them during her reelection campaign against Republican challenger Tudor Dixon, who ran on a school choice and parents’ rights platform.

Still, the education agenda Whitmer put forth Wednesday was meatier than the plan in her 2022 State of the State address, which proposed investing more in education but introduced no specific new school programs.

Whitmer begins her second term with a $9.2 billion state budget surplus, including $4.1 billion in the school aid fund. Some lawmakers will be looking to reinvest that money in state programs, while others — Republicans and Democrats alike — are eyeing tax cuts.

Whitmer has both in mind. In her speech she reintroduced her plans to repeal a 2011 law that taxes retirees on their pensions and to expand the Working Families Tax Credit.

“Data shows boosting the Working Families Tax Credit also closes health and wealth gaps,” she told lawmakers Wednesday. “Children who grow up with this support have better test scores, graduation rates, and earnings as adults.”

Whitmer also used Wednesday’s speech to tout her first-term accomplishments. Those included creating a fellowship program for education majors, paying student teachers, and expanding school mental health programs.

“We made record investments in our children and schools by leading with our shared values,” she said. “We closed the funding gap between schools. We brought student investment to an all-time high four years in a row without raising taxes.”

Preschool plan would be open to all 4-year-olds

Whitmer’s ambitious early childhood proposal, which would be rolled out over four years, would lift current restrictions on eligibility for the Great Start Readiness Program, paving the way for every 4-year-old in the state to enroll.

“This investment will ensure children arrive at kindergarten ready to learn and saves their families upwards of $10,000 a year,” Whitmer said. “It helps parents, especially moms, go back to work. And it will launch hundreds more preschool classrooms across Michigan, supporting thousands of jobs.”

There are an estimated 116,000 4-year-olds in Michigan, and about 35,000 are enrolled in GSRP statewide. To qualify for the program today, a family of four must make less than $70,000 per year or face other barriers such as homelessness.

The proposal would add Michigan to a growing list of about a dozen states with universal preschool eligibility. Those states vary widely in the proportion of eligible 4-year-olds who are actually enrolled.

Some providers celebrated the idea, saying it would allow them to reduce paperwork and enroll more children.

“I would go for that,” said Princess Dobbins, who operates three child care centers with GSRP classrooms in the Detroit area. “The only reason we’ve got so much paperwork is the (enrollment) restrictions.”

Whitmer offered few details about how the program would work or how much it would cost. The GSRP budget is currently $418 million; a spokesman for her office said the expansion would be funded in the short-run using the state’s historic surplus. Advocates said they expect more information when the governor releases her budget recommendations in early February.

Key questions include how expansion plans would address chronic early educator shortages, how they would affect the rest of the early childhood landscape, and how much programming families of preschoolers would receive. GSRP programs offer care four days per week.

Educator shortages have hampered the most recent expansion effort. Whitmer tapped federal COVID aid for a large GSRP expansion in 2021, but the state has struggled to find teachers to staff the new classrooms necessary to reach her enrollment goals.

“We’re already lagging in terms of uptake, and we’ll continue to have that lag if we don’t address the talent issues,” said Denise Smith, implementation director for Hope Starts Here, a nonprofit early childhood initiative in Detroit. She suggested that the state could require GSRP programs to pay teachers a living wage as a condition of receiving the new funds.

Advocates also worry that expansion could cause problems for child care programs that enroll 4-year-olds and younger children. Four-year-olds are less expensive to care for than younger children because they require less supervision; drawing them away from community-based child care could make it harder for those programs to continue serving younger children.

“That’s the elephant in the room,” said Matt Gillard, president of Michigan’s Children, an advocacy group. He said his understanding is that the Whitmer administration plans to put together “a panel of experts to figure out how we can fashion this in a way that mitigates those impacts.”

Tracie Mauriello covers state education policy for Chalkbeat Detroit and Bridge Michigan. Reach her at tmauriello@chalkbeat.org. Koby Levin is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering K-12 schools and early childhood education. Contact Koby at klevin@chalkbeat.org.