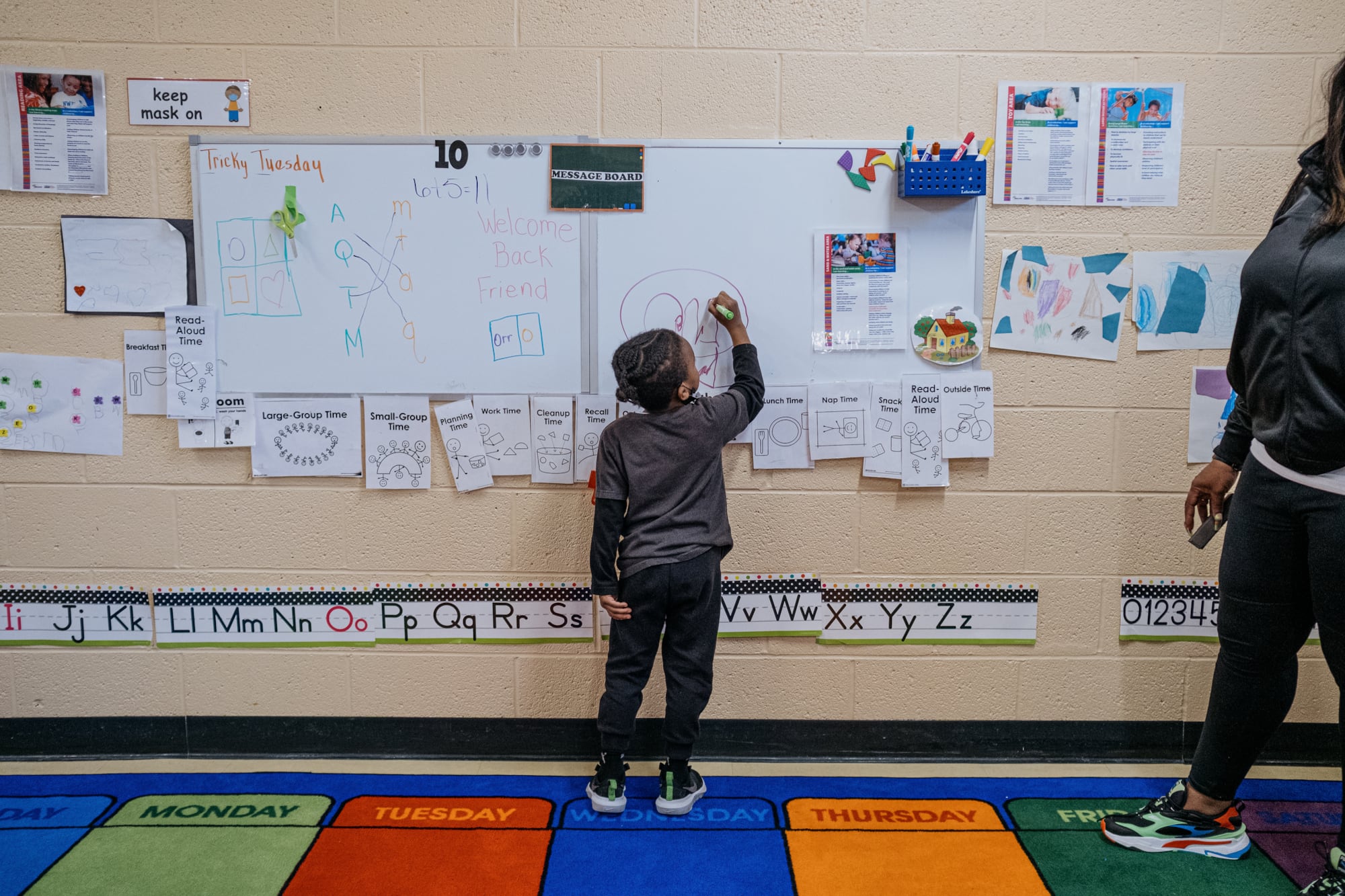

Nina Hodge is willing to forgo some of her salary to make sure she can continue paying her employees at the Above and Beyond Learning Childcare Center in Detroit.

“They deserve a living wage,” said Hodge, the director and owner of the center.

She and other child care providers in Michigan are preparing to take drastic measures now that federal COVID relief funds that helped keep many centers afloat during the pandemic ran out Sept. 24. That relief came in the form of increased reimbursement rates providers received for low-income families who receive child care subsidies from the state.

Those higher rates were considered temporary during the course of the pandemic because they were funded with federal dollars that would eventually expire. Although the new rates are higher than they were before COVID, providers will still see a big reduction from what they became used to during the pandemic.

“Child care reimbursement rates may not fully support the true cost of quality, including offering competitive wages to attract and retain child care workers,” the Michigan Department of Education said in a letter to providers and families about the end of the temporary rates.

Early childhood advocates have been sounding the alarm about the loss of this money and the consequences for providers and the families who rely on their services. Without state intervention, they say, some providers will close, leaving child care workers out of work and the neediest families without child care services. Other providers, they say, will reduce services or increase their rates, or both.

A handful of organizations sent a letter last week to every Michigan lawmaker, urging them to “prevent an approaching child care disaster” by approving a supplemental budget that would maintain the funding levels that recently expired. In the letter, they said rates are declining by 26%. Department officials said they had not calculated such a percentage.

“We need new state investment now more than ever to help stabilize child care operations in Michigan. Without needed new investment, it is certain more child care businesses will close leaving a projected 56,000 young children without stable care outside the home,” the letter said.

The organizations that signed on to the letter were Michigan’s Children, Michigan Association for the Education of Young Children, Think Babies Michigan, and Michigan League for Public Policy.

The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank, projected in a report earlier this year that nearly 56,700 children would lose child care services due to the drop in reimbursement rates.” That report predicted the child care funding cliff would cause 1,261 Michigan child care facilities to close. Nationwide, the foundation projected 3.2 million children to lose services and more than 70,000 facilities to close.

Some national early childhood experts, however, have taken a more conservative tone. They told Vox they don’t expect the impact to be as great, in part because some states have invested heavily in child care in recent years.

Michigan’s child care system already struggling

But if the dire predictions become true in Michigan, it would further destabilize an already troubled early childhood system.

A 2022 Muckrock investigation concluded Michigan’s child care system was in crisis, with far more so-called deserts — areas of the state where demand far outweighs available slots — than policymakers had estimated. Meanwhile, staffing challenges have made it difficult to hire staff, and low wages have providers competing with other industries for workers.

In May, more than 100 people picketed and chanted outside Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s Detroit office, hoping to raise awareness of challenges in the industry and demanding more funding than lawmakers had already proposed in the state budget.

“This industry is broken to begin with,” said Matt Gillard, president and CEO of Michigan’s Children, a nonprofit advocacy organization. “It’s going to require increased public investment at both the state and federal level to solve the child care problem.”

Gillard said he hopes Michigan lawmakers act on the message in the letter his group and others sent last week. He said Michigan is “the only state that has Democratic control that has not really moved significantly to offset the reduction of the reimbursement rates with increased state resources.

“There’s a real fear out there that we’re going to see a significant number of providers either go out of business or maybe stop taking children that are eligible for a subsidy and focus their efforts on families who are able to pay higher amounts,” he said.

Michigan has done some good things, Gillard said, including a plan to transition the state to provide universal free preschool to 4-year-olds, regardless of income. Michigan has also gone to a system of reimbursing providers based on enrollment, not attendance, which would provide guaranteed funding.

Stacey LaRouche, a spokeswoman for Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, cited the recent investments, including the expansion to universal preschool, in a statement to Chalkbeat. But she didn’t say whether Whitmer would push to maintain the pandemic-era rates. LaRouche said Whitmer also set a goal to open 1,000 new child care programs, and the state is 90% of the way to that goal.

“We will continue to closely monitor childcare access and strengthen our economy by helping parents return to work knowing their children are safe and learning,” LaRouche said.

For now, providers such as Hodge are planning for the worst. She had a recent meeting with her accountant in which she discussed plans to reduce the salary she pays herself from $50,000 to $30,000. Reducing the wages of her employees isn’t an option, Hodge said.

“These are the people who keep our economy going, who keep our economy thriving,” she said.

That’s precisely why there was so much effort to keep child care centers afloat during the pandemic, because essential workers needed places to send their children while they worked on the front lines of the health crisis.

Up north in Traverse City, Anna Fryer is the director and co-owner of Teddy Bear Day Care and Preschool, which has three locations in the city. Starting in 2020, the federal relief money helped subsidize salaries for workers during a delicate time when “our bank accounts were dwindling.”

To address the loss of the money and rising costs, the business recently raised its rates by between 5% and 6%. It was not an ideal decision, she said, “because we don’t want to tuition ourselves out of business.”

Lori Higgins is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Detroit. Reach her at lhiggins@chalkbeat.org.