Sixth grader Ke’Von Thomas and a group of classmates at Detroit’s Durfee Elementary-Middle School sat around a cafeteria table one day last month, running through a list of 10 back-to-school tips and vying to see who had completed the most.

“Early to bed, early to rise,” was the first tip. Others included “establish a routine,” “organize your backpack,” and “limit screen time.”

Ke’Von, 11, said he had accomplished three tips since the school year started, and surveyed the others. “I did No. 1. You did No. 2,” he told one of the other boys. “Who else did No. 2?”

Across from him, seventh grader Miguel Perkins said he had followed five of the tips.

The list and the exercise came from The Konnection, a community group that’s working with Detroit schools to help motivate students to show up for school and “move the needle” on chronic absenteeism. Founder Sharnese Marshall uses the lesson early in the school year to reinforce positive attendance and academic habits with 20 middle school students who participate in a biweekly after-school program at Durfee.

In a city with sky-high rates of chronic absenteeism — meaning students who miss 18 school days a year or more — community groups like The Konnection have taken on some of the work of trying to improve student attendance. Churches, after-school programs, health centers, and other groups have provided services such as driving students to and from school, conducting home visits and phone calls, and building connections with families.

These groups don’t necessarily have the resources to attack what experts agree is the root cause of chronic absenteeism: Detroit’s widespread poverty, whose ripple effects include health problems, housing instability, and job barriers. So it’s hard to determine what impact they’re having on the broader problem.

Nonetheless, they have become an essential complement to the efforts by school officials and education advocates to improve attendance. With initiatives targeted at specific schools, neighborhoods, or family needs, they’re chipping away at a problem that has long undermined efforts to improve student achievement. And school leaders and district officials are embracing some of their efforts and strategies as part of their approach to reducing chronic absenteeism citywide.

Sarah Lenhoff, a Wayne State University education professor whose research includes studies of student attendance, says there’s room for still more community groups and local agencies to get involved at the root-cause level.

“Poverty alleviation, employment, job training, housing stability — these are major factors in whether kids can get to school,” Lenhoff said. “Outside organizations that are working on those issues, even if it’s not connected to the school system, could also make a difference.”

DPSCD attendance plan evolves

Community groups have been working with Detroit school communities on absenteeism for more than a decade. But the Detroit Public Schools Community District formalized and standardized their role in attendance interventions beginning in 2018-19, a couple of years after the district emerged from state control.

Related: Detroit community groups have a long record of attendance work

That year, DPSCD outlined a plan that called for a holistic approach to improving attendance through wraparound services for students, hiring attendance agents, and partnerships with community organizations. The plan fell in line with growing consensus among advocates and national experts that districts should collaborate with local partners to support school-based attendance interventions.

Partly as a result of that plan, DPSCD reduced its chronic absenteeism rate to 62% at the end of 2018-19, from 70% the previous year.

The pandemic not only erased that progress, but raised the urgency of improving attendance: If students didn’t show up for class, they would struggle to recover what they lost academically during a year or more of online schooling.

And the effects of excessive absenteeism linger for years, research shows. Students who miss a lot of school are likely to struggle to stay on top of classwork, perform worse on standardized tests, and are more likely to drop out. Chronically absent students are also likely to miss out on high-dosage tutoring and other interventions school systems have prioritized in recent years to counter learning loss.

A 2022 study by the Detroit Partnership for Education Equity & Research found that the district’s 2018-19 attendance plan, while showing early success, “only partially addressed chronic absenteeism as an ecological issue, implicitly downplaying structural and material barriers that families faced.”

It’s those systemic issues, Lenhoff said, that require better coordination between the district and city agencies and social services organizations, such as welfare and employment programs, and housing organizations.

She points to FosterEd Arizona, a child welfare program that coordinated with schools to improve attendance among foster youth, as well as a multiyear attendance effort in New York City that collaborated with city social service agencies. In both cases, school attendance data guided the implementation of interventions.

“There’s potential to really make a difference if we got more groups involved in the community development space who are working on housing, poverty, and unemployment, to be thinking about how might we track the attendance of the families that we’re working with and demonstrate that work like this could be beneficial,” Lenhoff said.

DPSCD Superintendent Nikolai Vitti said that because of federal education privacy laws, the district has to work within some limits on how much information it can share with outside social service groups. It does share attendance data with some community groups that provide programming for students, such as City Year and Communities in Schools, he said.

But that’s not possible for all groups without getting permission from individual families or through clearance. It is unclear how the Arizona and New York programs have been able to share attendance data with social service agencies.

“We could envision our district portal system providing access to partners so they can respond to negative attendance trends,” Vitti said. “However, this would take signoff from families and significant upgrades to the system we are building now. This would be impossible without a robust technology system. You cannot rely on spreadsheets to make this work.”

Since the start of the pandemic, DPSCD officials have rapidly expanded their wraparound services for some of the most marginalized families, embracing the kinds of projects that community groups have been tackling in specific communities.

With the help of $4.5 million in philanthropic donations, DPSCD is launching 12 school-based health hubs across the city over the next several years to address the lack of student access to health care, a major barrier to consistent attendance.

At the health hubs, students, families, and community members can get physical, mental, and dental health services through current partnerships with Henry Ford Health and Ascension. They also have access to food pantry items and legal support.

One of the first few health hubs opening this year is at Durfee and Central High School, which share a building in the city’s Dexter-Linwood neighborhood. At the sites that are already open, families have been making health appointments and picking up health essentials like toilet paper, soap, and toothbrushes.

“We believe in whole child commitment,” Alycia Meriweather, DPSCD deputy superintendent of external partnerships and innovation, said at a recent community meeting on the new initiative.

The Konnection responds to lack of basic supplies

Durfee and Central have among the highest absenteeism rates within DPSCD: 82% at Durfee last year, and 91% at Central. It’s why Marshall and The Konnection began working there as far back as 2020.

Some students told Marshall they were not showing up to school because they didn’t have personal hygiene products or clean clothes. Others said school is boring, or they’re behind on work and don’t have the support to catch up.

On top of those challenges, in-school factors such as student-teacher relationships, bullying and safety concerns also create barriers to attendance.

Marshall responded to those needs by throwing quarterly attendance celebrations at Durfee, and setting up a school-based resource closet at Central, stocked with supplies students need to feel comfortable coming to school.

In the past year, the program’s closet served 275 high school students.

“Bullying is a real thing,” Marshall said. “Kids are bullied every single day because they don’t have the nicest clothes, or because they don’t smell the freshest.”

Enrichment programs help students stay motivated

They also launched the after-school Konnection Klub at Durfee, with enrichment programs that make coming to school more engaging. Several studies find that student participation in out-of-school programs can improve regular school attendance, encouraging students to show up to class.

This year, The Konnection is collaborating with local entrepreneurs and colleges to help students explore career opportunities in culinary arts, podcasting, fashion design, and transit services. Students in the after-school program also receive mentoring from community volunteers, practice social-emotional learning activities, and attend field trips to city sports and holiday events.

“Schools may be supporting (students) academically,” Marshall said, “but enrichment programs can help you mentally and emotionally. They can help you in other ways that other partners can’t.”

Marshall worked with Durfee’s attendance agent and teachers to select participants who could most benefit from the program’s offering. They sought a mix of students who are chronically absent and those who are not.

“We want the students who are not there to feel supported by the leaders of the school who are showing up and who do understand the assignments,” she said. “We try to find a couple in each grade who are great students and do have support at home so that they’re able to pull the other kids up.”

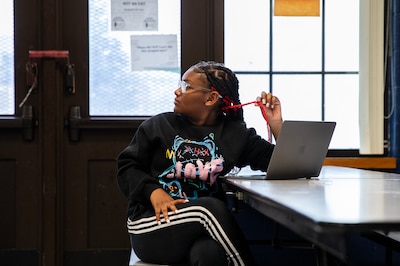

Ke’Von (pronounced “kay-vaughn”), one of the students with strong grades and near-perfect attendance, had been eager to join the program since last year, when he was in fifth grade.

Leona Wright, an eighth grader at Durfee, was one of the students who needed the added support. She has routinely missed school on Mondays and Fridays this year, days her mother, Shavonne Jones, has to work late.

Jones works as a cook in a nursing home in Bloomfield Hills, about a 30-minute drive from Durfee. She says that between her and her fiancé's work schedules, it has been difficult to consistently get Leona to school on days they are both working.

“On Mondays, I have to be at work at 6 in the morning,” she said. “Then on Fridays, I go to work at 10:30, so I can take her to school but I won’t be able to pick her back up from school.”

Jones added: “There’s just a lot of difficulties with that. My job is understanding sometimes, but most jobs don’t want you to leave like that during the day.”

The family lives outside of the school’s boundary for yellow bus transportation as well, and Jones isn’t comfortable with her daughter riding the city bus.

One week in November, Leona was sick with the flu, prompting Jones to stay home from work to take care of her.

Marshall has sought out different solutions to some students’ transportation barriers, offering families Uber gift cards, asking volunteers to offer rides, or directing families to resources already available via the district, such as free bus passes.

Running the after-school program until 5:30, she added, provides some flexibility to families who can’t make the regular afternoon pickup time.

“It definitely helps the parents who are working, because a lot of times the kids are going home by themselves or they’re just hanging out in school,” Marshall said.

Leona says she’d rather be at school than at home. Prior to this year, she was homeschooled for four years and missed connecting with other students in person. Back at Durfee, she’s excited about trying out for the school’s cheer team and studying math, science, and social studies.

And she was eager to join The Konnection. “I wanted to make friends and experience my life and go on field trips,” she said.

The Konnection hopes to extend its reach

With a small team, Marshall has leaned on the support of roughly 150 volunteers in the past year to operate the resource closet, mentor students, and host attendance celebrations. She’s hoping The Konnection’s efforts can make more of a difference at Durfee. Last year’s chronic absenteeism rate was down 12 percentage points from the previous year, mirroring a decline across the district as quarantine restrictions eased.

“It’s still very high, but we’re making strides to be able to get that down,” she said.

She wants to see the program reengage younger students who may already feel disenchanted with school, or who might have lacked access to the resources, instruction, and extracurriculars the program provides.

In addition to attendance rates, The Konnection also tracks grade improvements, personal confidence, and “students’ desire to want to come to school.”

In a survey at the end of 2022-23, she added, 95% of club participants said they felt more motivated to attend school after being in the program.

This year, Marshall’s team is looking to reach at least 1,000 students across all its programs. They’re in the process of setting up a second resource closet at Durfee, and strengthening their relationships with community members outside the school.

The ultimate goal is still the same, she said: that “100% of our students will be on track in terms of attendance.”

“We’re trying to just bridge the gap where we can,” she said. “Until the policies are changed in order to ensure that our kids and our families are really taken care of and they’re not left out, the same issues will continue to perpetuate.”

Ethan Bakuli is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering Detroit Public Schools Community District. Contact Ethan at ebakuli@chalkbeat.org.