As a product of the Detroit public school system, where I now teach high school English, I care deeply about my students. From time to time, I like to ask them how they’re doing. But my check-ins aren’t always welcome.

A student once asked, "What did I do?" when I reached out to him. He was only 13, but this Black male student had already learned to expect a reprimand when teachers called his name.

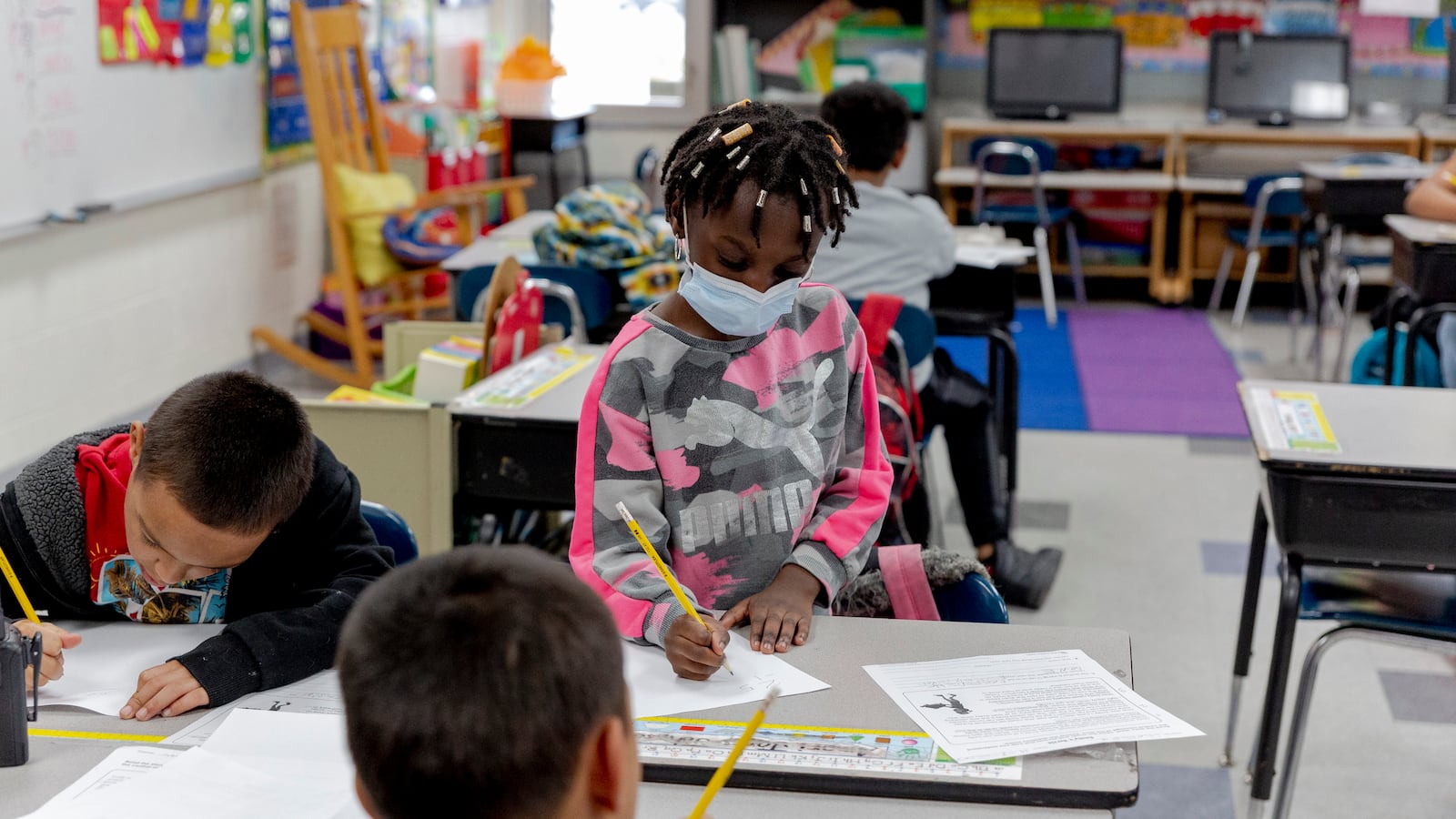

Black students are constantly dealing with the effects of what Dr. Lamar L. Johnson, an associate professor at Michigan State University, calls racial violence. It teaches children like my 13-year-old student to confuse the attention of caring adults with punishment. In the classroom, this violence can play out through language and curriculum, too.

Learning materials approved by the state and local school districts often omit critical conversations about the intersections of race, gender, religion, language, and sexuality. What's missing, in other words, is the lived experiences of students who are supposed to engage with the text.

Instead, Black children are molded into a life that is not theirs. Many of the books I'm told to teach to my kids center Eurocentric narratives and beliefs and whiteness. I am required to teach Abraham Lincoln and how he signed the Emancipation Proclamation, but not about the felony disenfranchisement that keeps many of my students' families from experiencing true freedom.

A recent NYU Metro Center report evaluated three commonly used elementary English Language Arts curricula: McGraw Hill's "Wonders," Savvas Learning Company's "myView," and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt's "Into Reading."

When students, parents, and educators from across the country assessed how the texts, teachers' manuals, and lessons honored students' diverse cultures and identities, they noted that the teachers' manuals for all three curriculums rarely guided teachers to connect lessons to students' lives. One evaluator observed, for example, that an elementary school teaching manual trivialized the devastation of colonialism and used dehumanizing language to describe Native Americans.

The assessment's disappointing (but unsurprising) results suggest too many students spend their K-12 years without the affirmation and support they deserve.

One approach to addressing racial violence and repairing the harm done to students of color is Becky Thompson's Teaching with Tenderness. This practice encourages educators to confront injustice directly while creating space for students' emotions and experiences. It's an approach I have adopted in my classroom. Over the years, going from pre-service teaching to being one of the district's 2022 Outstanding Educator awardees, I have seen its transformative power.

He was only 13, but this Black male student had already learned to expect a reprimand when teachers called his name.

This approach encourages teachers to understand who is in their classroom and use this knowledge to build the curriculum. You can't center your students' cultures and identities if you don't know their cultures and identities.

What does this look like in practice? In 2019, I worked with my 11th graders to research our classroom's curriculum.

We asked, "Who is this book made for, and why?" I won't soon forget our discussions. Students asked why the curriculum didn't include texts about powerful people who looked like us rather than "sad stories that look down on Black people."

We worked to improve the situation by compiling new resources, reshaping our lessons, and moving away from Eurocentric narratives in our classroom.

Teaching with tenderness is one way to address some of the well-documented challenges in Detroit schools and across the nation. Eighty-two percent of Detroit Public Schools Community District students are Black, and 13.6% are Hispanic/Latino. My district's National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, test scores in math and reading are the lowest among big-city school districts for fourth and eighth grades. I have taught high school students reading on a third-grade level, and the majority of the students I engage are behind in literacy proficiency.

My district also has one of the worst chronic absenteeism rates in the country. Almost 80% of Detroit district students were chronically absent — missing at least 10% of school days —in the 2021-2022 school year. Nationally in the same school year, at least one-third of students were on track to be chronically absent.

While teachers and faculty are scrambling to keep students in their seats, systemic racism pushes many of our children out of school because they feel safer in their community than in the classroom. Culturally responsive curriculums — lessons in which students see themselves reflected — can nurture a sense of belonging, thereby improving student engagement, attendance, and academic performance.

When children are not used to being loved wholeheartedly, their hypervigilance can perceive tenderness as a threat.

Our children deserve love and dedication from highly trained teachers who can identify and dismantle racial violence. This requires fully funded schools and community-based wraparound services.

We must not relent in the face of budget cuts, discipline disparities, and detractors who think softness is an unessential luxury. Tenderness can be the hardest skill to cultivate.

An educator, steering committee co-chair, and curriculum lead for National Black Lives Matter at School, N'Kengé Robertson is a voice for new, innovative educators in Detroit working to change educational paradigms for youth. She is a high school English teacher, a '22 NCTE Early Educator of Color Leadership awardee, and a proud native of Detroit.

This story has been updated to reflect that Teaching with Tenderness is an approach promoted by Becky Thompson, not Becky Johnson.