Justice McCalebb was nervous when he walked into his guidance counselor’s office at Martin Luther King Jr. Senior High School last November. The Detroit school district senior had fallen behind in his classes during the pandemic and needed to make up nine credits in math, English, science, and history — roughly two years’ worth of classes.

McCalebb hoped the counselor would offer a way to stay on track for graduation. But he didn’t expect to be pulled out of his school.

That’s what ended up happening. McCalebb was told he’d be moved to West Side Academy of Information Technology and Cyber Security — an alternative school in the district — within a matter of days in order to complete his credits.

To McCalebb, being pulled out of MLK and being sent to a new school didn’t seem like a fair solution.

“I feel like I could have completed it all if I stayed there,” he said.

McCalebb is one of a growing number of Detroit Public Schools Community District students who have been funneled to credit recovery courses after falling behind and finding themselves in danger of not graduating on time. In credit recovery, students take self-guided online courses, in which they view instructional videos and take multiple-choice question tests to pass.

The number of Detroit students taking credit recovery courses jumped during the pandemic, going from 2,742 high school students during the 2019-20 school year to peaking at 7,480 students last school year, about half of the roughly 14,000 high school students the district enrolls each year.

This year, 4,901 high school students in the district are enrolled in credit recovery – still nearly double the pre-pandemic numbers.

School districts have long tried to help students quickly earn course credits by using credit recovery programs. But the numbers have increased in Detroit and around the country as schools try to recover from pandemic-related disruptions that left many students off track for graduation due to failing grades, absences, and challenges with online learning.

Detroit district officials rapidly expanded offerings of credit recovery, encouraging students short on credits to make up courses during their regular class schedule, after school, and on weekends. So far that strategy has paid off: The district’s four-year graduation rate rose for the first time in nearly a decade.

“If students do not pass certain classes, then they cannot receive a high school diploma. Period,” said DPSCD Superintendent Nikolai Vitti. “We are changing the expectations, climate, and culture in our high schools by moving students on a clear path to graduate in four years.”

But while credit recovery appears to be improving graduation rates, some argue that it comes at the expense of face-to-face classroom time for students.

Students such as McCalebb who are sent to alternative schools are pulled away from close friends and school activities, which creates more disruption for already struggling students. If they are already behind grade level in core subjects, those students miss critical learning time. Experts say credit recovery alone doesn’t address the root causes of their academic challenges.

Graduation rate improvement hinges on credit recovery

As more students have enrolled in credit recovery programs, Detroit has seen an encouraging trend in its graduation rate.

In the 2021-22 school year, DPSCD’s four-year graduation rate rose to 71.1%, up from 64.5% in the previous school year. At this point last year, in the middle of pandemic disruptions, roughly 23% of high school students were on track to graduation. This year, that has improved to 56%.

“The improvement in graduation rates is a testament to our continued commitment to improve the high school experience for our students,” said Vitti in a recent news release.

“The course recovery work, especially as a product of the pandemic, has been grueling for staff and students but everyone refused to make excuses and our students benefited by graduating in four years.”

During the pandemic, Michigan’s high school graduation rate fell by 1.6 percentage points between 2020 and 2021, the first decline in years. In Detroit, graduation rates had been declining since 2015-16.

Detroit board members have called on the district in recent years to do more to address literacy levels and declining graduation rates.

““I am really outraged at the numbers,” board member Sonya Mays said last July during a school board meeting, referring to the 2019-20 school year. “We are still having hundreds of students leave this district without something as basic as a high school diploma, and I just find that really outrageous.”

Vitti has attributed that declining graduation rate in part to some of the city’s lowest-performing schools being reincorporated into the district in 2017, and more recently, the pandemic’s impact on student attendance.

As an increasing number of students failed to log in to online classes during the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years, the district used some of its COVID relief funding to offer teachers extra pay to teach additional courses during the day and to provide after-school courses to help students make up missed credit.

Credit recovery alone can’t help struggling students

As credit recovery programs have risen in popularity among school districts in the past decade, teachers and experts have raised concerns about potential drawbacks.

“It feels like the district is panicking after offering students ‘grace’ during the lockdown and virtual year, only to realize that the graduation rate was going to drop because kids didn’t have enough credits to actually graduate by state standards,” said Kelsey Wiley, an English teacher at Cass Technical High School.

The increased load of credit recovery, Wiley added, has hindered students from participating in after-school activities or being able to work after school.

In most cases, online credit recovery programs can be a “good model” for students who have already demonstrated a mastery of the curriculum material they missed, said Jordan Rickles, a principal researcher at the American Institutes for Research, who studied credit recovery programs.

The programs can allow students who have fallen behind the chance to test out of certain units. But those programs alone can’t make up for the circumstances that may have made a student fail a class in the first place.

“It’s not that they just need to retake an algebra I class and they’re good to go,” Rickles said. “It’s that these students have been, for a multitude of possible reasons, disconnected from school, or their attendance rates are much lower than the average student.”

Carolyn Heinrich, a professor of public policy and education at Vanderbilt University, found in her research into credit recovery programs that students least prepared academically were more likely to be set back by or struggle with online remedial courses, particularly those far behind grade level in core subjects.

And graduation rates, Heinrich said, while an important gauge of school quality, don’t necessarily equate to readiness for life beyond high school.

“We’re not going to make online credit recovery go away because it’s inexpensive, it fills an important need, she said. “But if we can do it better, so the kids … don’t have to trade off learning for passing courses, that’s what we need to do.”

Creating credit recovery programs that are of high quality, Heinrich added, through the use of in-person instructors, small class sizes, and progress monitoring, is the challenge facing high schools.

Vitti maintained that “no student is falling through the cracks” and that a pathway to recovery is available for those who end up in a “credit hole.” During his tenure as superintendent, the district has emphasized providing wraparound services for academically struggling students.

Over the course of the pandemic, DPSCD began actively monitoring each student’s credit status once they entered high school, he said. High school principals, according to Vitti, are now equipped to spot early warning signs of struggling students following their first semester of ninth grade.

“Being behind a couple of credits or classes is recoverable and manageable if the student is willing to put in the extra work and sacrifice,” Vitti said. “Most of our high school students do this.”

But some students end up missing two or more years worth of credits by their junior or senior year and, “it becomes more difficult for the traditional high school to catch these students up.”

Students in that situation can transfer on their own or are switched by school officials to alternative schools, as McCalebb was, where they are enrolled full-time in credit recovery. West Side Academy – one of the district’s alternative high schools – saw the highest improvement in graduation rates across DPSCD in the 2021-22 school year, rising by 25 percentage points.

“The West Side graduation rate data speaks for itself as an effective strategy to catch students up with credit to ensure they graduate in four years or even graduate at all,” Vitti said.

Students make up courses at expense of classroom time, extracurriculars

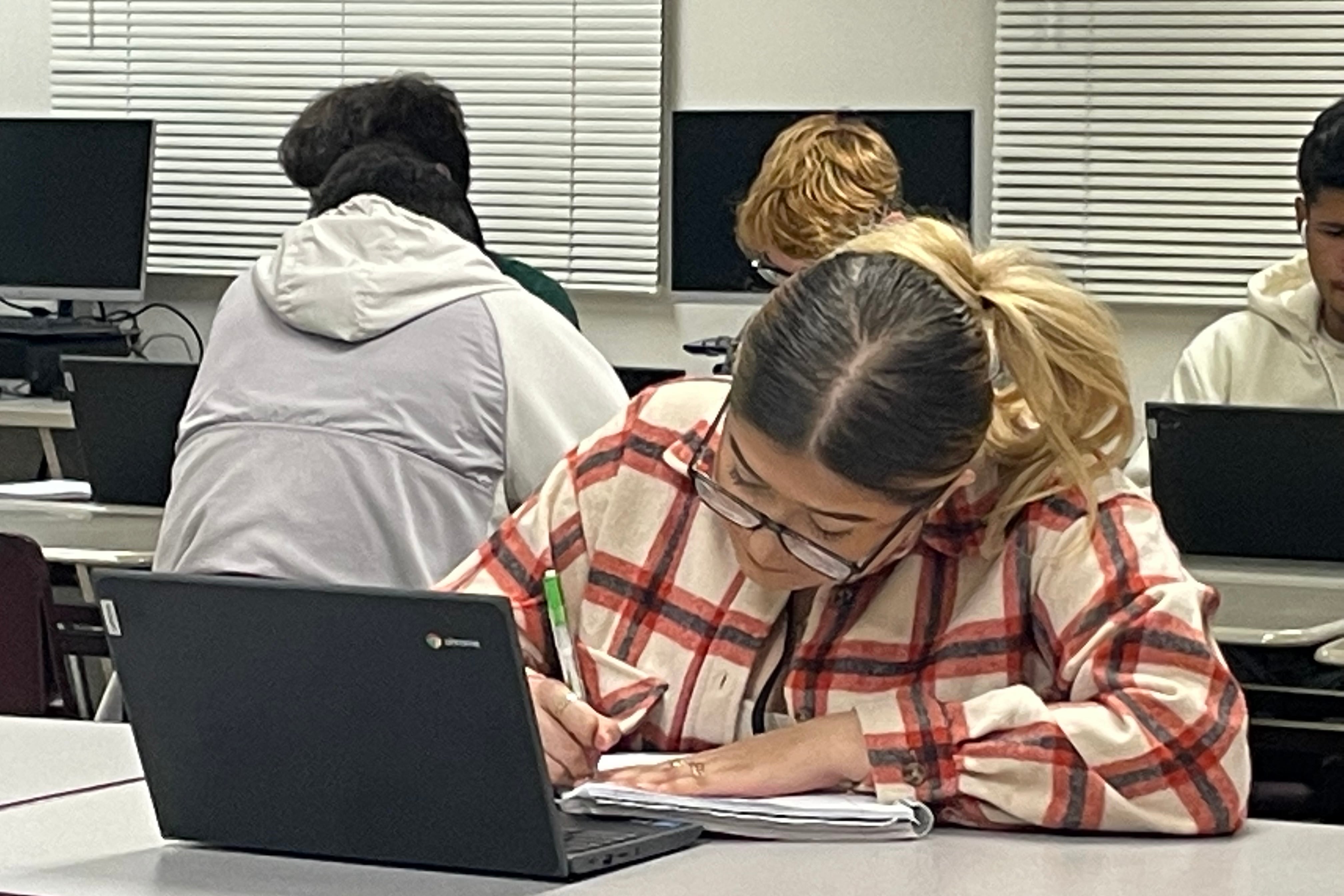

At West Side Academy, where Justice McCalebb was sent in the fall of his senior year, students complete courses through Edgenuity, an online curriculum that uses pre-recorded videos to speed students through core lessons. While teachers are in the classroom for additional support, students progress through multiple-choice assessments at their own pace.

Several months after being transferred from King, McCalebb is still irked over the decision. He’s been told he won’t be able to return to that campus, because King operates on a semester schedule while West Side runs on a quarter schedule.

In his first month at the alternative school, McCalebb estimates he breezed through 10 classes – without, he says, actually learning much. Many of the assignments covered material he had already been taught at King.

McCalebb often thinks about the opportunities he’s missing out on at King — after-school programs such as Lyrical Crusaders, a club where students perform spoken word poetry and hip hop, and C² pipeline, a college and career readiness initiative offered through Wayne State University.

McCalebb, who was behind nine credits when he came to West Side, is now on track to graduate this spring. But the disappointment about the transfer looms large over his senior year.

“There’s absolutely nothing I like about West Side,” he said.

With high school almost in the rear-view mirror, McCalebb is weighing his post-graduate options. At first, he had considered a few local colleges. Now he has pivoted his attention toward enrolling in a trade school next year.

Ethan Bakuli is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering Detroit Public Schools Community District. Contact Ethan at ebakuli@chalkbeat.org.