Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy.

After missing four days of classes last fall at Gompers Elementary-Middle School, Jay’Sean Hull was called into the cafeteria with 100 other students with similar attendance records.

The group was introduced to attendance agent Effie Harris, a key figure in the school’s efforts to improve on a dismal statistic. The previous school year, a staggering 82% of students in the northwest Detroit school were chronically absent, meaning they missed 18 or more days.

Harris explained that the students had been selected for a relatively new program pairing students at risk of becoming chronically absent with 20 adult mentors in the building.

Jay’Sean’s mentor: Harris herself. Over the next few weeks, she would greet the sixth-grader at a side entrance designated for middle schoolers, visit him in his classrooms on days that he arrived late, and regularly check in with his family.

This high-touch, relationship-based investment was part of a multipronged approach at Gompers last school year to tackle a problem with tragic consequences: Chronically absent students are more likely to become disengaged from school and more likely to drop out, research shows. Frequent absences also make it harder to get students on track academically, a pressing need coming off pandemic-fueled declines in academic achievement.

Gompers Principal Akeya Murphy, a veteran educator, tapped just about every staff member to help with the effort. Along with the mentorship program, the school dispatched staff to students’ homes to help families solve problems contributing to absenteeism, used data to track attendance patterns, and offered incentives ranging from field trips to the local movie theater for students to grocery store gift cards for parents.

Murphy, Harris, and other leaders at Gompers set an ambitious goal for last school year: to shave 20 percentage points off the school’s chronic absenteeism rate.

To get there, they would need to reach students like 13-year-old Jay’Sean, and dozens of other students whose absences put them at risk of missing out on their education.

“By the time they’re 16, they’re already thinking about going to work or exiting out of the educational system, because it is rigorous,” Murphy said. “We know the curriculum is rigorous, and so we want to prepare them, and the way we do that is by them being at school every single day, so that they’re not missing anything.”

Attendance struggles reflect Brightmoor’s economic challenges

Across the Detroit Public Schools Community District, 77% of students were chronically absent during the 2021-22 school year, when COVID-19 cases in Michigan reached their peak. But even before the pandemic caused a spike in absenteeism in school districts across the country, students in Detroit district and charter schools were missing school at crisis numbers.

The reasons for that vary, but they’re largely rooted in the economic challenges that accompany Detroit’s high poverty rates — transportation hurdles, health problems, family and housing instability.

Brightmoor, where Gompers is located, is one of the most economically challenged areas in the city, with a high concentration of housing instability, poverty, and transportation challenges. They contribute to a high level of transiency among the school’s student population, school officials say.

At Gompers, 91% of students come from low-income homes. The list of reasons for missed school days ranges widely at Gompers, from inflexible parent work schedules to student illnesses and bullying.

By January 2023, Haydin Griggs had missed about 50 days of the school year, primarily because her mother, Shetaya Griggs, had health problems that often prevented her from walking her daughter to school, and she didn’t want the sixth-grader walking to school on her own in their rough neighborhood.

Many parents “don’t have a bunch of money, they don’t have a whole bunch of resources,” said Harris, the attendance agent. “They’re thinking about just surviving.”

The Detroit school district’s strategies to reduce absenteeism have increasingly focused on these economic challenges. The district’s Family Resource Distribution Center regularly offers toiletries, dry goods, school supplies and winter coats.

The district is also set to launch 12 school-based health hubs in the next three years to provide medical resources and services that families would need to keep students attending school regularly.

One issue that came up at Gompers ahead of the school year was how many parents were holding their children back from school because they did not have a uniform or clean clothes. Murphy said she sent out a back-to-school letter encouraging parents to send their kids to school regardless of what they had to wear.

“We would prefer them to be at school and just have them wear their regular clothes versus feeling like they can’t come to school because of a uniform,” she said.

When Murphy became principal at Gompers at the start of 2022-23, she made sure to move the attendance agent’s office into the main office, a decision she hoped would amplify the importance of student attendance to families as they walked into the building.

Harris spends a portion of her days reaching out by phone and in person to parents and caregivers, trying to help them make plans to get their kids to class. It can be difficult, she said, stressing to families how two absences a month can quickly add up to a student being chronically absent. Some are unaware of how significant the absences are, and many are weary of the pandemic’s impact on their health, jobs, and households.

“The dust is still settling,” Harris said in February, during a spike in absenteeism. “Families have been affected, loved ones have been lost. There have been readjustments, people have had to adapt to whatever their new normals are and a lot of shuffling.”

A student’s absence, whether excused or unexcused, still counts toward the total number of missed school days they accumulate in a given year.

Gloria Vanhoosier’s three elementary school-age children each accumulated over 80 absences (out of 180 days) during the 2021-22 school year.

In Vanhoosier’s case, a bedbug infestation that lasted more than a year was a contributing factor. She was often too exhausted to take her children to school after spending so much time trying to rid her home of the critters, while also doing her children’s laundry nightly so they didn’t bring the bugs to school. They also missed school because of multiple of COVID infections, because of car problems, and because the children sometimes overslept.

Alarmed by the absences, Harris reached out multiple times asking Vanhoosier to meet with her at the school.

“‘I’m not superwoman,’” Vanhoosier remembers telling Harris when they finally met. “‘I got too much on my plate. I’m trying to take care of my kids and trying to take care of my family.’”

“Once I opened up to her, it’s like her whole face changed,” Vanhoosier recalled. “Now I feel that she sees my struggle and is concerned for me.”

The conversation with Harris motivated Vanhoosier to rethink her attitude about her children’s absences and its impact on their grades. Seeing her daughters happy and thriving after they began attending school more regularly has also helped. The girls participated in volleyball step dance, and after-school tutoring programs.

“I’ve gotten a lot better,” Vanhoosier said in the spring. “We still miss days, but I’m open with her now.”

Absenteeism has ripple effects on students in the classroom

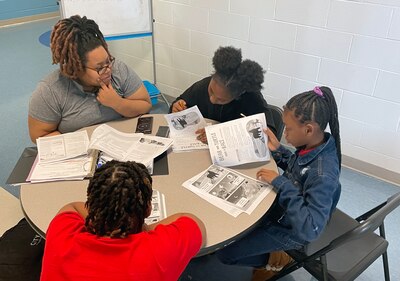

Brittany Parker, who has been teaching for 10 years, wrestles with what to do when her kindergartners don’t show up for class. Absences can create lasting turmoil in a child’s education — children who are chronically absent in early grades are less likely to read at grade level by the third grade.

They can also hamper the rest of the class. “The question for me is: Do I push ahead to the next lesson or do I wait for them to come back?” Parker said.

“As a district, they want us to keep going,” she said. “If it’s four kids out, I’m going to push ahead. Sometimes if it’s a larger number I’ll hold back. I’m also looking at: Are these kids who can catch up?”

By May, more than half of the 50 third-graders La’Dawn Peterson taught between her morning and afternoon math classes were chronically absent. An additional nine were severely chronically absent, meaning they had missed more than 36 days of school.

One of them missed more than 60 days during the year.

“He would be so good if he came to school,” Peterson said of the boy. When he did show up, he was able to grasp the material, but she worried whether he’d retain the information.

Despite her many attempts to communicate with his family, she said she’s not entirely clear why he was absent so much.

Peterson said she’s tried exhaustively to impress upon her students and their families the importance of daily attendance, and the harmful impact of missing school. It shows up in their academic performance, she said, and explains why some students can become classroom distractions.

One day in June, when extreme heat prompted the district to shorten the school day, just nine students showed up — about half as many as usual. One of them was the boy who had missed 60 days.

On that day, while other students quickly got to work on their online multiplication and fraction exercises, he was slow to get started. He rubbed his eyes with the sleeves of his black and white Adidas tracksuit, and rested his head on one hand as he clicked through the exercises.

About 10 minutes later, he raised his hand, and a classroom tutor walked over to his desk in the back corner of the room. With a little bit of support, he seemed to grasp the lesson and began to work through the exercises.

Teachers like Peterson are cramming in four to five lessons a week, and they depend on weekly small-group lessons to catch up absent or struggling students. But if kids miss those opportunities, the challenges multiply.

“They’re missing out on so much and then, most of the ones that are absent all the time … there’s no motivation at home,” Peterson said. “So they come to school, and they’re not motivated to do anything.”

Over 18 absences: ‘You can’t bounce back from that’

Eighteen days. Thirty-six days. Fifty days. Sixty days. Eighty days of missed school. How does a student’s attendance record ever get so bad?

That’s the question that haunted Murphy and her team at Gompers, and motivated them to work on curbing absenteeism long before it becomes chronic.

“You want to, for lack of a better word, stop the bleeding,” with students just below chronic absenteeism, Murphy said in January. “We need (families) to know that they’re on their way to being over the 18 absences … you can’t bounce back from that.”

In Jay’Sean’s case, it was four missed days of school by the end of October, too many so early in the school year. Jay’Sean blamed inconsistent school bus service that prompted him to start walking to school.

That was enough to warrant an intervention from the new mentorship program for him and the other students at risk of becoming chronically absent. The school’s mentoring program is an offshoot of a national initiative launched by the U.S. Department of Education.

The program’s premise sounded easy enough to Jay’Sean. “I just had to keep coming to school,” he recalled.

In reality, it took more effort than that from Harris and others on the team to ensure that Jay’Sean stayed on track. But it worked.

“By the beginning of the new year … he was always coming,” Harris told Chalkbeat this summer. If Jay’Sean came in late some days, she’d stop by his classroom to check in.

“He always wants to go to school,” said Shamika Hull, Jay’Sean’s mom. “He’ll go stand outside, and it’ll be raining, and he’s out there waiting for the bus.”

Hull also has an 11-year-old son at Gompers who got the message on attendance.

“The only times they have been absent from school since (the program began) has been either they were having a doctor’s appointment, or I wasn’t able to wash their clothes.”

For those whose absences are already beyond the “chronic” threshold, Murphy said she and her staff “continue to work with the family. We continue to make those calls. We continue to try to remove barriers.”

Those efforts won’t help the school improve its chronic absenteeism rate, Harris said, “but it’s still going to help the kid.”

“I tell them, ‘OK, let’s just take it a week at a time. Just five days. Four more days. Just three more days,’” she said, adding: “It’s going to make a difference for the kids and their scores.”

Attendance incentives are a ‘means to an end’

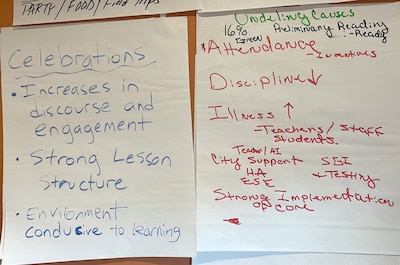

The conference room at Gompers is testament to the school leaders’ determination to make a dent in absenteeism. On all four walls are dozens of easel paper sheets, with handwriting in bright pink, green and orange marker. Each sheet details strategies Gompers staff have employed to try to make kids come to school every day.

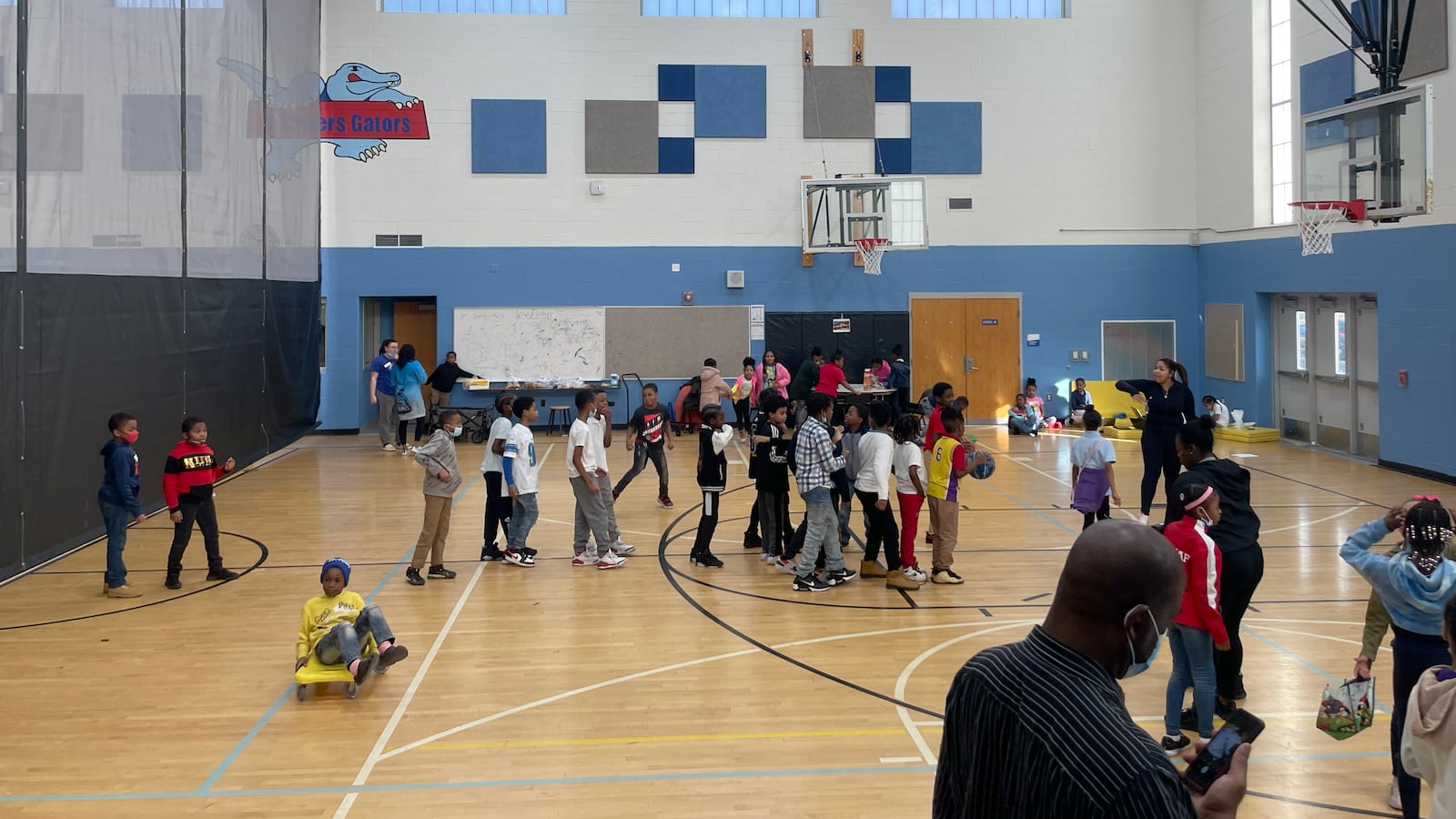

Field trips to the local movie theater and bowling alley. Gas and grocery store gift cards for parents. Arts and crafts activities in the gymnasium. A mobile video game truck. “Gator Bucks,” named after the school’s mascot, for students who complete classroom assignments and exhibit positive behavior.

“These are the kinds of things that we’re discussing, constantly thinking and trying to be innovative about,” Murphy said. “How can we entice kids and make sure that families are consistently bringing their children to school?”

“It’s a means to an end … initially to draw them in and then to get them into the habit” of going to school, said Harris, the attendance agent.

A line of plastic trophies sit on a shelf behind Harris’ desk. Every two weeks, the awards go to the classrooms that have the most students with perfect attendance.

Gompers deploys some of these incentive programs when students are more likely to be absent, such as before and after holiday breaks or crucial days such as Count Day or state testing periods.

But while incentives are a significant part of Murphy’s vision to encourage student attendance, relationship building remains the core tenet of the school’s efforts.

“Children need to know that you care for them, that they’re in a safe space, that they have a trusted adult that they can communicate with and someone that is building a relationship with them, because that’s going to open the pathway for learning,” she said.

When absences go unexplained

For all their efforts — and progress — the sense of crisis is never far away.

On a Friday morning in early February, a handful of master teachers and administrators gathered in that same conference room for a weekly meeting to discuss academic performance, attendance, and behavior.

It had been close to a month since students and staff returned from winter break. And yet, teachers were still reporting near-empty classrooms.

“It’s that two-week break, where a lot of our students are moving,” said Shannon Harper, a fourth grade master teacher. “They may have been (evicted from) their homes. They may be living now with a relative, and there’s some friction there. And cars break down in the winter, especially here with all the potholes.”

“I just had a student that was out for 10 days,” Harper told the group. “We don’t know why, and he doesn’t either.”

Despite a barrage of robocalls going home when a child is absent, many parents don’t send their children back to the building immediately. And even when students do return, some may not have notes or reasons explaining why they missed school.

“If you never say this is your issue, we can’t help you,” said Adrian Harrell, Gompers’ parent outreach coordinator. “We can’t see what our next solution is to help you. All we know now is they are absent.”

After a year of effort, Detroit students and leaders reap the rewards

On the last day of school, the grin on Jay’Sean’s face was hard to conceal, even behind the black hoodie that shrouded his head.

He was one of nine students who won a new bike in an end-of year-raffle to reward students who showed up every day over the last weeks of school.

As he took a seat on his red and black Mongoose bicycle, Jay’Sean welcomed the compliments and cheers from his friends.

The whole school had something to cheer about, too. By the end of the year, the chronic absenteeism rate declined to 64% — just shy of the 20-point decline school officials were aiming for, but down significantly.

The district experienced a similar decline, from the peak of 77% in 2021-22 to 68% last year. District officials attribute some of that to the end of quarantining requirements that forced many students to miss school.

Encouraged by the progress last year, Gompers school staff plan to continue their strategies in the new school year that began this week.

The mentoring program will remain in place, along with the range of incentives the school experimented with. But most significant for Gompers will be the addition of a second attendance agent to work alongside Harris.

Superintendent Vitti announced earlier this year that the district would shuffle its 80 attendance agents to schools in areas with the highest concentration of chronically absent students and poverty.

The added resources provide validation that attendance agents with a coordinated, hands-on approach can make a difference.

Harris said she is proud of seeing her mentees like Jay’Sean avoid chronic absenteeism. He finished the year with 13 absences, five days below the threshold.

Under Harris’ guidance, he found an accountability system that worked for him. By the end of the winter break, for all the attempts he made to get to school on time and every day, he and other students earned snacks and mini-parties every month.

With a challenging sixth grade year behind him, Jay’Sean is ready to get back to school.

Ethan Bakuli is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering Detroit Public Schools Community District. Contact Ethan at ebakuli@chalkbeat.org.

Tracie Mauriello covered state education policy for Chalkbeat Detroit. Reach the team at detroit.tips@chalkbeat.org.