Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy.

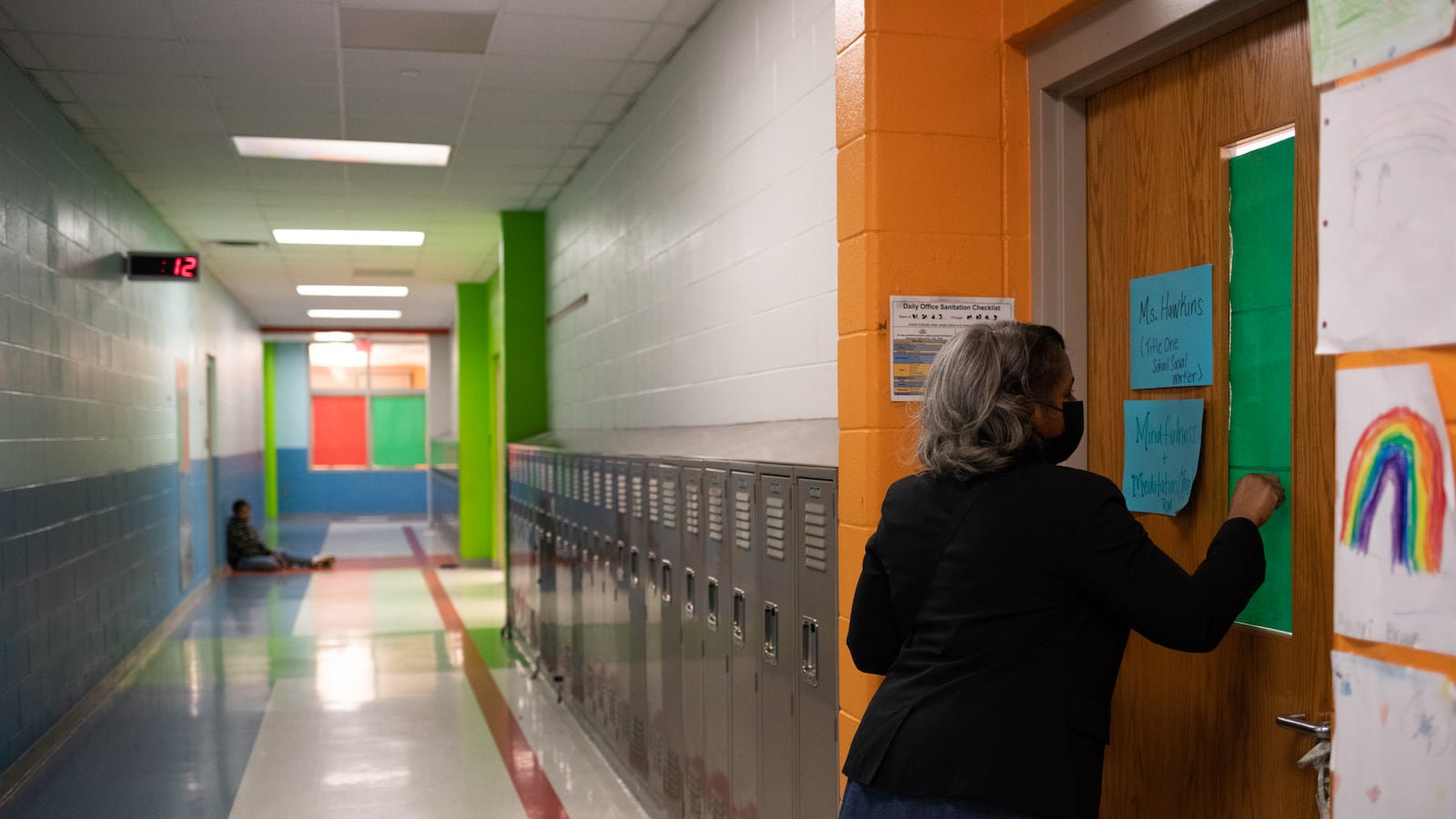

Effie Harris can’t walk down a hallway at Gompers Elementary-Middle School without having to stop several times for a hug, a high five, or a promise of a crayon drawing.

Her pauses have to be quick, though. She has places to go and students to see.

By 8:04 on a cold February morning, she had already been at school for an hour, greeting students at a side entrance for middle school latecomers. After a quick stop in her office to drop off her coat and sanitize her hands, she began her morning rounds.

First stop: Room A115.

“I was just checking to see if she was here,” Harris called out. The teacher inside knew who Harris was talking about: a struggling second-grader who was absent as often as present. On that day, the child was present.

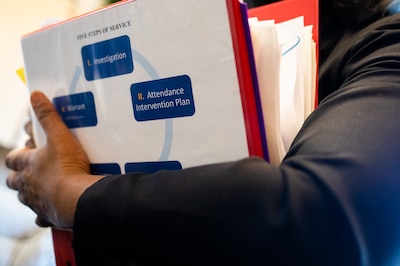

The spot checks only begin to explain the expansive role Harris plays as Gompers’ attendance agent. Unlike the stereotypical truant officers of yore, who might round up troubled youth and drag them back to school, Harris must often serve as investigator to find out why children aren’t coming to school, visiting homes and keeping track of data on barriers to attendance. She is a counselor who listens to families and helps them find resources they need to get their kids to school.

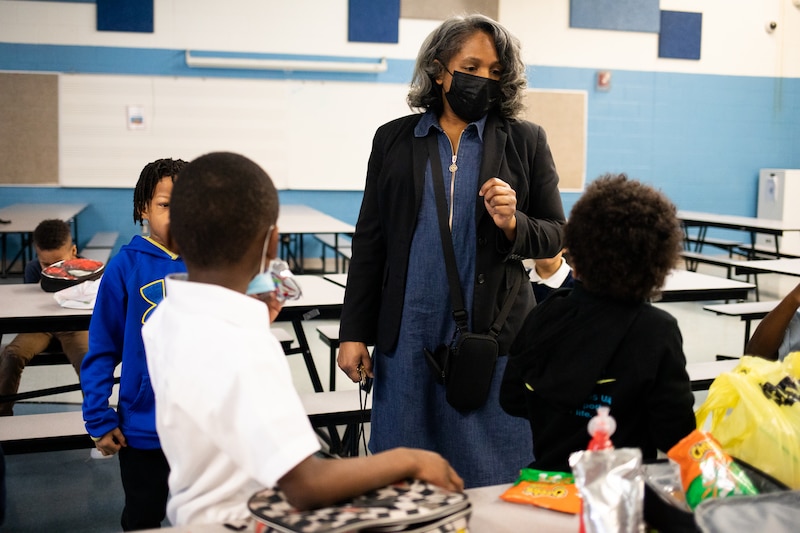

She is the school’s spirit leader for good attendance, showing up in classrooms with prizes — pencil cases, Hot Wheels cars, bubbles — for students who make it two weeks without missing a day. She plans pizza parties for classes with the best attendance, and helps teachers plan fun activities that children won’t want to miss.

And sometimes, she must play bad cop, warning parents of children who are severely chronically absent that they could face legal or financial consequences.

After the stop in A115, Harris moved on toward another classroom, greeting everyone in the halls as she breezed past — by name if she knew it, or if she didn’t, with a “Mornin’, sunshine!” or a “Good morning, sweetie!” One elementary school child wrapped her arms around Harris’s legs, and soon she was surrounded by others who wanted her attention, too.

Harris’s goals that day were to check in with nearly two dozen middle school students who were approaching 18 absences, attend a school leadership meeting, call a few parents of chronically absent children, fill in for an absent teacher as a lunchroom monitor, and make a banner reminding kids to show up on Feb. 8 — one of two “count days” during the year when attendance is used to determine how much state funding a school gets.

She walked around the school with a large binder that she uses to track absences and excuses, and interactions with families. Every month, she must provide a report to the district.

“I’ve never been able to get through the volume of work that I’ve wanted to,” she said.

Why aren’t Brightmoor students getting to school?

When a parent shows up, Harris drops everything to listen.

A day earlier, she said, an exasperated mother showed up in her office to tearfully explain why her three children had each missed about 20 days.

“I said, ‘I’m going to get you a tissue, and I’m going to get me a box, because I might be crying, too, today.’”

Harris had reached out to the mother before and even tried to make home visits, but no one ever answered the door. This time was different.

“When she came in, she was at a breaking point,” Harris said. “It was a different conversation. It didn’t seem like she was on the defense. It seemed like she was open” to explaining her struggles and working on a plan.

“We want to find out the whys to offer solutions, to find out how can we help,” Harris said. “That’s the big thing. It’s not doing anybody any good just to stir things up and not to have a solution.”

Gompers serves some of the neediest children in Detroit, a city challenged by high levels of poverty, homelessness, unemployment, and crime. Most live in Brightmoor, a 4-square-mile area that’s impoverished even by Detroit standards. It’s the kind of neighborhood where 1 out of 5 homes is abandoned, and a local diner has 3-inch bulletproof glass separating the serving counter from the dining room.

Some parents keep their children home from school for fear of what they may encounter on the way, especially in winter when it’s still dark out. School starts at 7:30 a.m.

“I can’t blame them,” Harris said. “Parents don’t want to walk them to bus stops in dangerous areas. … I tell the parents, you guys have to get them to the bus stop. This is just your reality. You’ve got to do that.”

About a third of Gompers’ 838 students come from other neighborhoods. Those students have their own attendance challenges. When the family car breaks down, they stop showing up.

Other students don’t come to school because they have to babysit younger siblings while parents work, or they live part-time with another parent in a different area. One mother last year kept her three children home because they were in hiding from her abusive partner.

Harris listens with an empathetic ear as parents explain the barriers standing between their child and the classroom — whether it’s homelessness, lack of clothing or transportation, bullying at school, inability to get up on time, or child care challenges.

Then she steps in. Sometimes she calls parents who’ve overslept to wake them up. Other times, she picks up children from their homes and drives them to school herself.

“We want to make sure we actually have practical solutions, and the other side of that is that parents have to be willing to follow those recommendations,” Harris said in an interview in her office.

A few minutes later she was on the phone with a parent whose three children hadn’t shown up to school.

The oldest child had a sore throat. She had a 9:15 a.m. doctors appointment, the mom said. But it was already 9:07, and they were still home. Harris began to wonder.

“Bring in documentation after she has her doctor visit, OK?” Harris asked.

The mother didn’t answer. She hung up on Harris.

It didn’t seem to bother her.

“Something more is going on,” Harris said, noting that she’d talk to the oldest child when she returned to school. “Elementary kids, I say, ‘OK, where were you?’ and then they’ll start to tell me.”

“It takes time to investigate, to find out what’s going on,” Harris told Chalkbeat in a later interview. “Sometimes it takes time for them to even warm up to you to talk about what’s going on.”

For now, there were other children to check up on.

Personal outreach to students: ‘I’m glad you’re here’

Harris headed upstairs and asked the teacher in Room A230 if she could have a word with a student. A few moments later, a boy emerged from the room.

“Good morning,” she said to him. “I’m glad you’re here. You doing OK?”

After a moment, she sent him back to class.

Next she headed to the classroom next door to check on his brother, who spoke quietly and rubbed his face on the sleeve of his hoodie.

Hours later, she was still thinking about him.

“He really looked tired,” she said, and the last time she saw the brothers they also looked exhausted. “But lately they have been here. They have been here, so that’s good.”

Before the start of last school year, Gompers Principal Akeya Murphy moved the attendance agent’s office into the main office, as a way to highlight the importance of student attendance to families as they walked into the building.

Once the school day begins, though, Harris doesn’t spend much time in her office.

“I like moving around in the building, going to the kids,” she said. “I like seeing them. I like interacting with them.”

Her next stop took her to the other end of the building. On the way she ran into a middle school student and greeted her by name.

“How many times am I going to see you next week?” Harris asks.

“I really don’t know,” the girl says.

“What do you mean you don’t know? What’s wrong?” she asks. “I want to see you every day.”

“OK. All right,” the girl responded, as if she meant it.

Help is on the way from the district

Being an attendance officer is a tough job in a district where year after year, more than half the students are chronically absent.

Harris’ role got even more challenging during the pandemic, when Gompers and many schools nationwide experienced a surge in chronic absenteeism. There have been days over the years when the sheer number of students who needed to be reached has been overwhelming.

“I had to get past that,” Harris said. “So many need to be helped. You can’t do everything. You can’t make it to everybody.”

Harris is getting more help this school year. A new district strategy involves assigning a second attendance agent to schools like Gompers with high rates of chronic absenteeism.

Harris empathizes with the families who are struggling. But she wants them to understand the consequences of their children not attending school.

“At the end of the day, this is who’s being hurt, and it’s your child. At the end of the day, this is who’s not being given the opportunity they deserve.”

Getting that message across successfully is one of the rewards of a tough job, she said. Take Gloria Vanhoosier, whose three children are “smart as a whip” but were absent for nearly half of the 2021-22 school year. After repeated calls home, Harris convinced Vanhoosier to come in for a talk about her struggles at home, and the importance of bringing the kids to school.

By the end of 2022-23, the children were doing much better with attendance. They still missed days, but not nearly as much as they had the year before. More importantly, they were doing better at school.

“Gloria is a fighter. And now we’re seeing the results. We’re seeing the benefits. She’s the one who sat in my office one time and said, ‘I tell my kids … it’s OK to struggle, but it’s not OK to give up.’ You are absolutely right. Because we all have struggles. We just don’t want to give up.”

Vanhoosier told Chalkbeat that talking to Harris was like talking to a therapist. Hearing that, Harris was full of emotion.

“Oh, I love it!” she said.

Tracie Mauriello covered state education policy for Chalkbeat Detroit. Reach the team at detroit.tips@chalkbeat.org.

Ethan Bakuli is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering Detroit Public Schools Community District. Contact Ethan at ebakuli@chalkbeat.org.