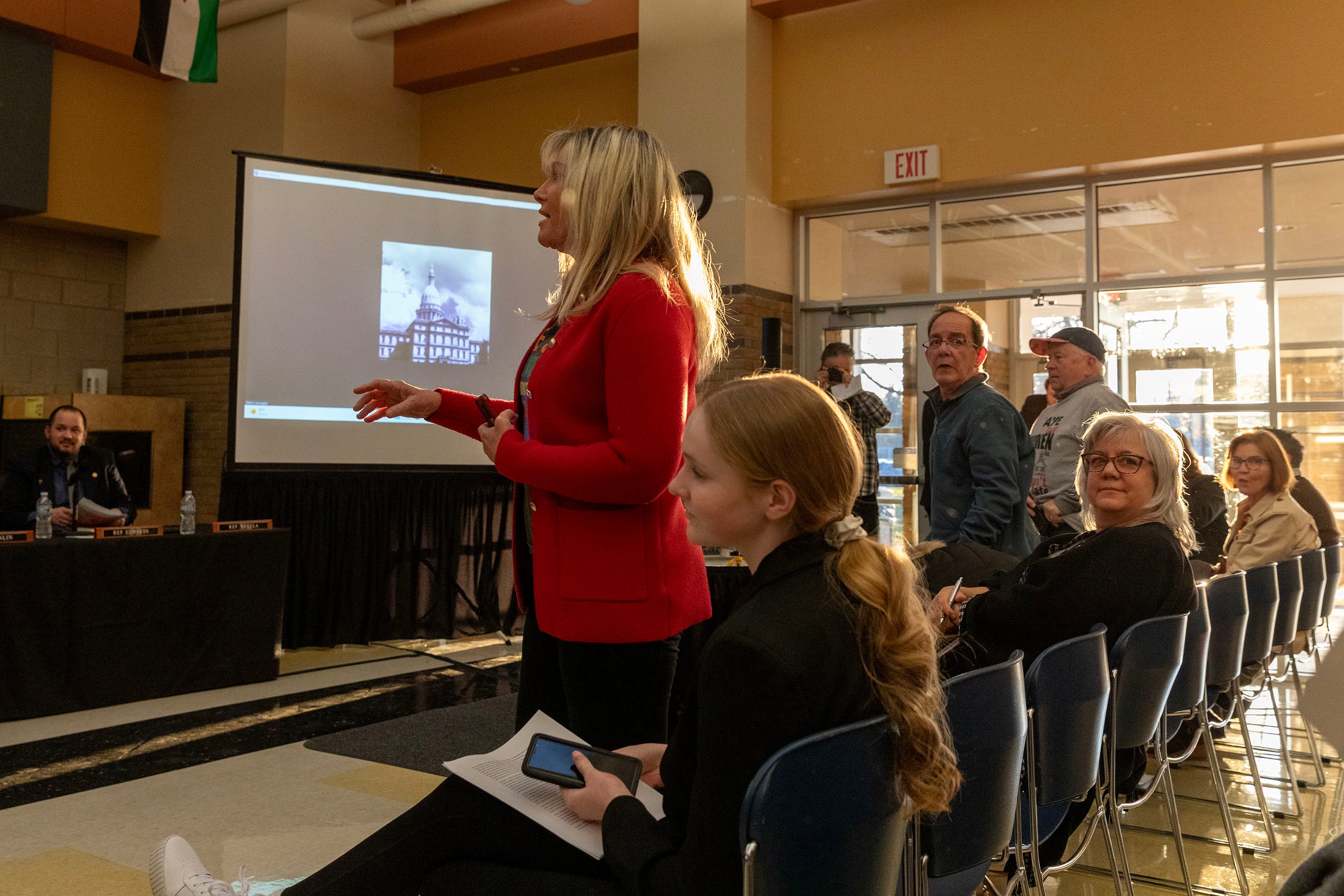

As a House Education Committee meeting ended last month, a group of home-schooling parents and community members began shouting at the lawmakers who wouldn’t allow them to speak.

“Coward,” they yelled out repeatedly at members of the committee.

They weren’t there to talk about shortages of mental health staff in schools, the topic of the meeting. Instead, they wanted to speak out against the possibility that Michigan might one day require home-school parents to register with the state.

Rep. Matt Koleszar, a Democrat from Plymouth and chairman of the House committee, has rankled home-schooling advocates by saying Michigan should require a registry. State Superintendent Michael Rice, who oversees the Michigan Department of Education and is the state’s lead educator, has said the same and is urging lawmakers to act.

Their comments have inflamed fears among home-schooling parents that their freedom to educate their kids at home might be taken away, and that a registry might be just the first step to do that. That’s despite Koleszar saying he has no plans to introduce legislation, and so far no other lawmakers have done so. Parents have vowed to resist calls for reforms and are showing up at meetings like the hearing this month and during the public comment period of State Board of Education meetings.

Kendele Sluka, a mother who home-schools her three sons in Sterling Heights, said she went to the meeting to show the representatives that a large community will fight for its right to educate their kids at home.

“It’s important to show your face and be ready to stand for the home-school community,” she said after the meeting. “I’m just ready to do what I need to do to keep it available in Michigan.”

No one knows exactly how many children are home-schooled in Michigan because home-school families are not required to notify the state or their local school district that they’re educating their kids at home. Not knowing who or where these children are is a concern, some state officials and legislators say.

“I fully respect and appreciate the ability and the right of parents to home-school their children,” Koleszar told Chalkbeat. “I have no objection. We just want to know they’re being home-schooled.”

Rice and some legislators have proposed requiring families to provide notification that they are home-schooling. In a letter earlier this year to Michigan lawmakers on legislative priorities, Rice said parents should be able to choose from among public (including charter), private, parochial, and home schools. But having a record of where children are would make it easier to know which children aren’t being educated anywhere, he said. He said, “the issue of ‘missing children’ is a national problem with potential negative consequences for too many children.”

Rice called the issue one of “student safety.”

“After the pandemic, we lost a lot of students. We don’t know where they ended up. Did they go to private school, parochial school? Did they begin home-schooling? It’s important for us to know that children are in fact being educated,” Koleszar said. “Simply registering or enrolling, even just to check a box to say, ‘I am home-schooling my child,’ at least lets us know where that kid is.”

Many home-school advocates have opposed a mandatory registration or notification system, in part because they say such a system will lead to increased government regulation of home schooling.

Michigan already has a voluntary home schooling registration system. The only home-schoolers who must register are those who need services from public schools or participate in their programs. For everyone else, it’s optional.

According to the Michigan Department of Education, 555 home schools had registered for the 2023-24 school year, including 821 students, as of Feb. 22. But that number is likely a small fraction of the actual number of Michigan’s home-school students, which is around 50,000 by some estimates.

At the committee meeting at Sterling Heights High School, Koleszar and the other representatives quickly left the room as security personnel and law enforcement officers watched as the group continued to yell.

“You said you want to hear from the community, but you didn’t give us an opportunity to speak at all,” Leanne Fisk, a mother who home-schools her daughter, said as she stood up and approached the committee.

The landscape of homeschooling in Michigan

Before 1993, if parents in Michigan wanted to home-school their children, they had to be teachers. But the law changed that year to allow parents to educate their children without a teaching certificate.

Since then, and especially during the COVID pandemic, the number of families home-schooling their children has increased dramatically. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the percentage of households home-schooling in the Detroit-Warren-Dearborn metro area increased from 3.2% in April-May 2020 to 15.2% in September-October 2020.

Michigan is generally considered friendly to home-schooling because it doesn’t regulate the practice the way many other states do — by having testing and curriculum requirements.

In New York, which has strict rules, parents must notify their local school district of their plans to home-school and submit reports outlining the materials and curricula they plan to use or their plan of instruction. They must comply with attendance requirements and keep attendance records. Their children must take a standardized exam or an alternative evaluation method. Meanwhile, in Oregon, where the laws aren’t as strict, parents must notify their local district that they are home-schooling, and their students must take academic tests at the end of grades 3, 5, 8, and 10.

“For 30 years, Michigan has been one of the best states in the whole United States for encouraging the home-school community and promoting home-school culture,” said Israel Wayne, vice president of the Michigan Christian Homeschool Network, or MiCHN.

“Thousands of families have actually moved to Michigan for the purpose of home schooling, and we’re seeing many of those families now say that if laws are passed to provide needless regulations to their families, that they will move to other states that do not have those requirements.”

MiCHN represents about 11,000 families in Michigan, and Wayne estimates that over 30,000 home-schooled students are part of their network.

Under Michigan law, children must be educated in mathematics, reading, English, science, and social studies. For grades 10, 11, and 12, instruction also must include the U.S. and Michigan Constitutions and civil government, and Michigan’s political subdivisions and municipalities.

The impetus to require notification

A few high-profile cases of home-schooled children who were abused or killed by their parents, and whose parents were not educating them even though they claimed to be, have spurred conversations about mandatory notification.

In December, Koleszar posted on X (formerly Twitter) that Michigan is one of only 11 states that doesn’t count or register home-schooled children. He also noted that “abusive parents are taking advantage of that to avoid being found out ... Michigan cannot allow this loophole to continue.”

A bill to require home schools to register was introduced in 2015, after two Detroit children were abused and killed by their mother, who claimed to be home-schooling them. That bill also would have required children to meet regularly with a mandated reporter of child abuse, such as a physician, social worker, or school counselor. The bill did not get a hearing.

“While I do recognize that a vast majority of home-school parents do everything they can to provide a good education for their children, there have been those rare circumstances where a child has been abused or has lost their life,” Koleszar said. “And when people ask me, ‘Well, it’s so rare — why have a law?’ I would argue that one child losing their life in this scenario is one child too many.”

Home-school advocates have argued that a notification system won’t improve safety. “Having a child’s name on a government database protects exactly no one,” Wayne said. “We already have a law in Michigan that says you’re not allowed to abuse your child, we have a law that says you can’t kill your child …. And yet, people who are law breakers, by definition, don’t obey laws,” so a registration won’t prevent such abuse.

“If it’s only putting your name on a list, then what was the point of it?” said Detroit parent Glenn Woodard, who home-schools his children, ages 9 and 13, with his wife, Jennifer Russell. “It’s kind of hard for me to believe that it is only going to be — you’re just going to go on a list. What does that do? That doesn’t do anything.”

Woodard pointed to one of the high-profile cases, which involved two couples who had adopted dozens of children and were charged with child abuse. “The impetus for this legislation belongs with the failings of the Michigan state Health and Human Services Department,” Woodard said. “The home schooling was not the issue.”

Wayne, of the Michigan Christian Homeschool Network, said, “We don’t believe that this is merely a registration.” It’s about “trying to get the students back into the public schools for revenue, but also very likely, an attempt on their part to try to create difficult regulations” that will make home schooling more cumbersome, he said.

Rice said the proposal is limited to a notification system. “We’re simply concerned that every child who has the right to an education receives an education in one form or another — is accounted for in one place or another,” he said.

Implications of a registry debated

Some home-schoolers have asked what happens after a child is registered.

“Who’s deputized, then, to follow up?” Russell asked. “Who’s deputized to go knock on doors saying, ‘Do you have children in your home? And are they home-schooled, or do they go to public school?’”

During the pandemic, Detroit mom Bernita Bradley started the home school co-op Engaged Detroit, which provides coaching for parents. She opposes requiring parents to register. But, in her work with Engaged Detroit, she advises parents to let their local schools know they’re home-schooling.

One reason she does this is that when kids don’t show up at school, schools will report the parent for truancy. “And truancy in cities like Detroit, in Wayne County — truancy means a court case for a family,” she explained. Parents who notify the school may avoid that.

Bradley said she also understands parents who think, “I really don’t want to let you know where I’m going, because you didn’t care enough to care about my child when my child was in your building.”

Bradley said she thinks there’s more scrutiny now that more people of color and people who are less affluent started home-schooling. And the rapid growth in home-schoolers in Detroit includes many Black families, she said. “I, quite frankly, look at it as this attack now that more Black families and more urban families, people of color, are choosing home school,” she said.

Also, the effects of a registration system in Detroit would differ from the effects in wealthier suburbs, Bradley said. “I think they will have a lot of people who would not report, and so there will be some type of pushback. And that’s scary, because then what type of legal ramifications are they gonna be seeing if people don’t report?” she said. “Historic accountability for brown and Black families has not looked the same.”

If a bill is introduced, it may answer some of these questions.

Both Rice and Koleszar emphasize that they want to mandate notification or registration to help clarify who’s being home-schooled, not to create obstacles for home schooling.

Noting that Michigan doesn’t regulate home-schooling the way many states do, Koleszar said, “I think simply adding a registry is the bare minimum standard. But it’s also a standard that I’m comfortable with.”