As a high school wrestler many years ago, Jon Wilcox was expected to help coach much younger students who were learning to wrestle. It was a role he embraced and one that helped cement his decision to go into teaching.

“Week after week, I’d have the same group that I worked with, so I think that consistency in getting to know them and then going to tournaments, and coaching them from the corner — that was definitely pretty powerful,” he said.

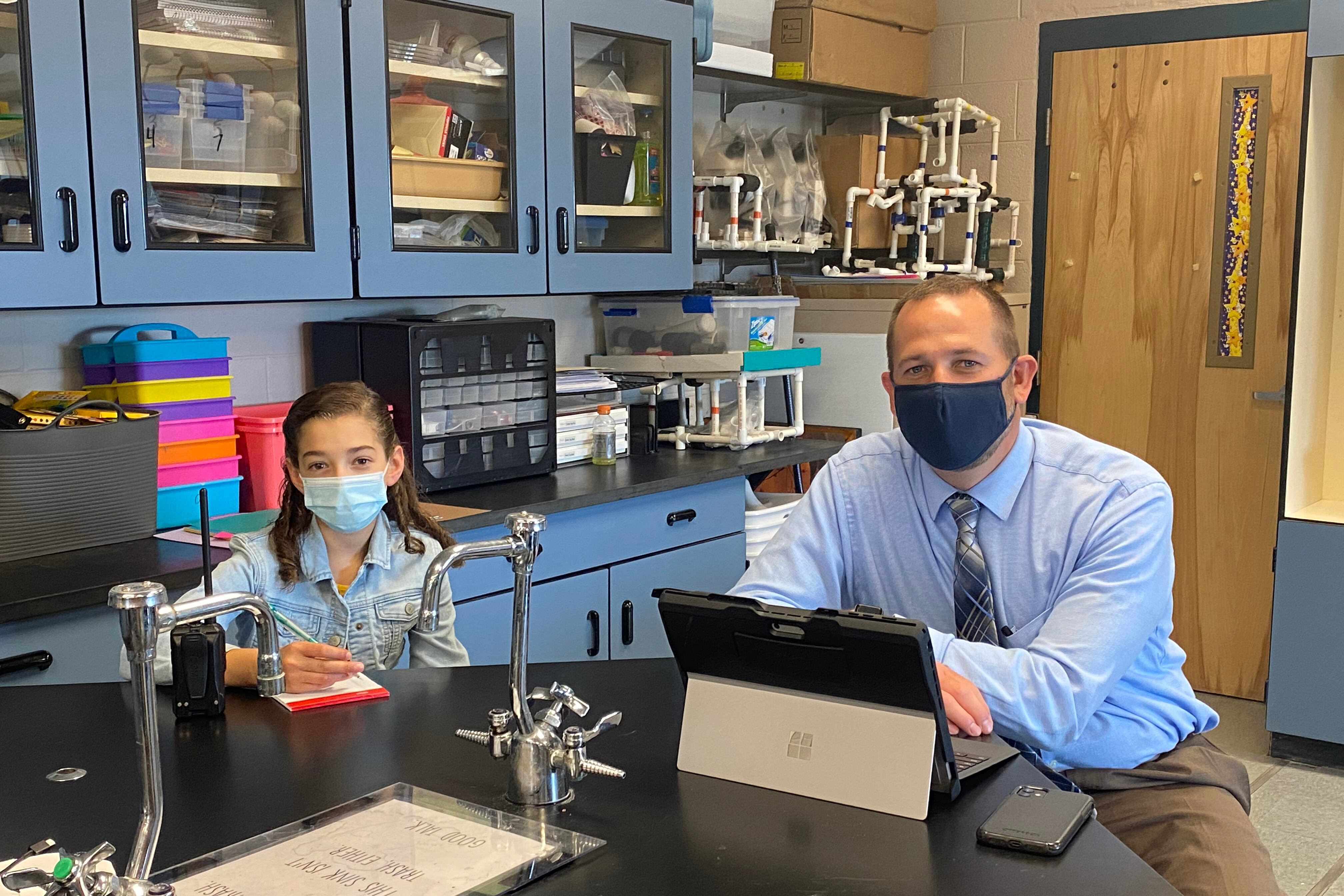

Wilcox, who was recently named Michigan 2024 Principal of the Year, is influencing students in different ways these days. For nine years he’s been the principal of Petoskey Middle School, a school of about 570 students, 42% of whom come from low-income homes.

Those who wrote letters of support for his nomination said he is focused on the well-being of children and their families, has created a positive culture in the school, and has a collaborative leadership style, according to the Michigan Association of Secondary School Principals and the Michigan Association of Student Councils and Honor Societies, which give out the award.

Wilcox prioritizes meeting the needs of students, especially post-COVID, when student anxiety is on the rise.

But middle school has always been a tumultuous time. So when less than a week into his tenure as principal, Wilcox was approached about funding for a behavioral health therapist at his school, he jumped at the opportunity.

“So many times a kid would get in trouble, and your toolbox is only so deep,” he said. “You try to counsel them as best as you can and then provide some kind of disciplinary action. And then it’s like, OK, now go back to the classroom.”

The school now has two behavioral health therapists, in addition to two counselors. Having that many people supporting the emotional and mental health needs of students, he said, “has been very beneficial.”

Educators can easily find themselves frustrated with the challenges students bring to the classroom that often seem unfair to the child, but something Wilcox heard years ago has provided some crucial perspective.

Parents, he was told, “send us their best … and they love their child more than anything.”

Wilcox, who recently talked to Chalkbeat, is always thinking about that because once students arrive at school, “We are responsible six, seven hours a day for the most important thing in parents’ lives. And that can be profound.”

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What led you to a career in education?

Like a lot of educators, I was fortunate enough to have some really good teachers during my time in school, and not only that, but it was kind of a family business. I have several cousins who went into education, and one of my brothers was a teacher. My grandpa was a principal and he was very well respected in the community. That kind of intrigued me. I think when I decided I was in high school, and I was helping out with our youth wrestling program, and I just liked working with the kids and, and that kinda helped guide my decision to become a teacher. My dad always talked about what a respectable career choice that is because you’re having an impact on the community and a direct impact on kids who might need a little more support.

Was there anything in particular that you recall that showed you what it meant to be a teacher?

I had a physics teacher who was also one of our assistant wrestling coaches. Our head coach was out, so this assistant coach ran the whole practice. After practice, he asked me ‘How did practice go? Is there anything I could have done better?’ And I remember thinking like, ‘Wow, he cares enough to ask me what I think.’ I mean, this was a physics teacher that I looked up to and regarded as a great teacher and for him to humble himself and ask … what I thought about practice — that was pretty powerful.

What issues have come up for you as a school leader this school year, and how have you addressed them?

In middle school, year after year, there’s a lot of student conflict. We’re dealing with the age group where kids are trying to figure out who they are and what they’re interested in. And sometimes that changes over time. They’re very different kids when they come in as a sixth grader [and] by the time they leave as an eighth grader. There’s a lot of growth that happens. And with that growth comes a lot of change and change in friend groups, and therefore some conflict with peers. We try to use those as teachable moments about being empathetic and accepting of others. ‘You don’t have to like everybody, but you do have to respect everybody’ is what we try to teach our kids.

How do you deal with middle school conflicts?

You hear the word bullying a lot, and absolutely bullying happens. But most of the time, it’s conflict between two students. Generally, it’s conflict that we can work through and resolve. So we do a lot of conflict resolution meetings where we have an adult … talk through a situation with both kids and try to help them gain the perspective of the other student. And then, you know, apologize, and there might still be a consequence, but we really focus on those restorative practices.

What’s the best advice you ever received — and how have you put it into action?

One thing I heard [came] during my master’s program in a class taught by a superintendent. He said, ‘Never make a decision that you can’t explain publicly.’ And I’ve thought about that I can’t tell you how many times. It’s not that you always have to explain your decision publicly. But I think that is a really good lens to make sure that your head is in the right spot when making decisions, because we often have to make really complex decisions. And just thinking that through, how would I explain this if I had to, that’s probably the quote that I go back to the most.

Petoskey is a tourist attraction in Michigan, but you work in a district where nearly half of the students come from low-income homes. How do you address the challenges that come with educating vulnerable students?

We do have a lot of socioeconomic diversity and that does present its own challenges for sure. One thing that we have incorporated is we call it our student support network. Each one of our grade levels is divided into teams, and a team of four teachers will have the same students, and then our counselors are part of those teams. We’ll have [meetings] where we intentionally talk about who are the students that are struggling. How are they struggling? What interventions work for this student? What have we tried that didn’t work? And we document all that. We try to be really systematic about making sure that no one’s falling through the cracks.

What’s one thing you’ve read that has made you a better educator?

If I had to pick one thing, I would say “The First Days of School,” by Harry Wong [and Rosemary Wong]. That’s a book that I would imagine most teacher preparation programs utilize. And if they don’t, I think they should. I read that when I was a freshman in college, and I still, whenever we hire new teachers, I reference that book. And whenever we have a teacher that struggles with classroom management, I will hand them that book and say, read this chapter. That’s a really good book that seems to not have aged.

In recent years, many students have faced mental health challenges. How has your team helped support them at this time?

We have two school counselors. And then two behavioral health therapists that are employed through the local health department. They have appointments with kids that need additional support. That’s really been beneficial for our students and their families. And the other thing is restorative practices [because] not everything needs to be solved with a hammer. In the last couple of years, we’ve increased the amount of special education teachers we have so their caseloads are smaller than in the past.

How do you take care of yourself when you’re not at work?

I was lucky to have worked under a principal who told me that you need to take care of yourself, and you need to spend time at home and away from school. So he helped me [understand] that you could spend 24 hours a day working and there’s still going to be work on your desk. So know when to leave it and to go home. My wife and I have four kids. So we are busy going to athletic events, practices, and plays. So that’s how we take care of ourselves; we just spend time together as a family. We do a lot of camping. And then I have a little hobby farm where we grow Christmas trees, and we’ve got honey bees. So that all keeps me busy. And I love doing that stuff.

You have honey bees?

My second oldest, he came home from school — I think he was in kindergarten — and someone had brought in a frame of honey for show and tell. And he was hooked on reading books and watching YouTube videos about bees. So he kind of got me hooked, and we’ve had these ever since.

Lori Higgins is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at lhiggins@chalkbeat.org.