Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy

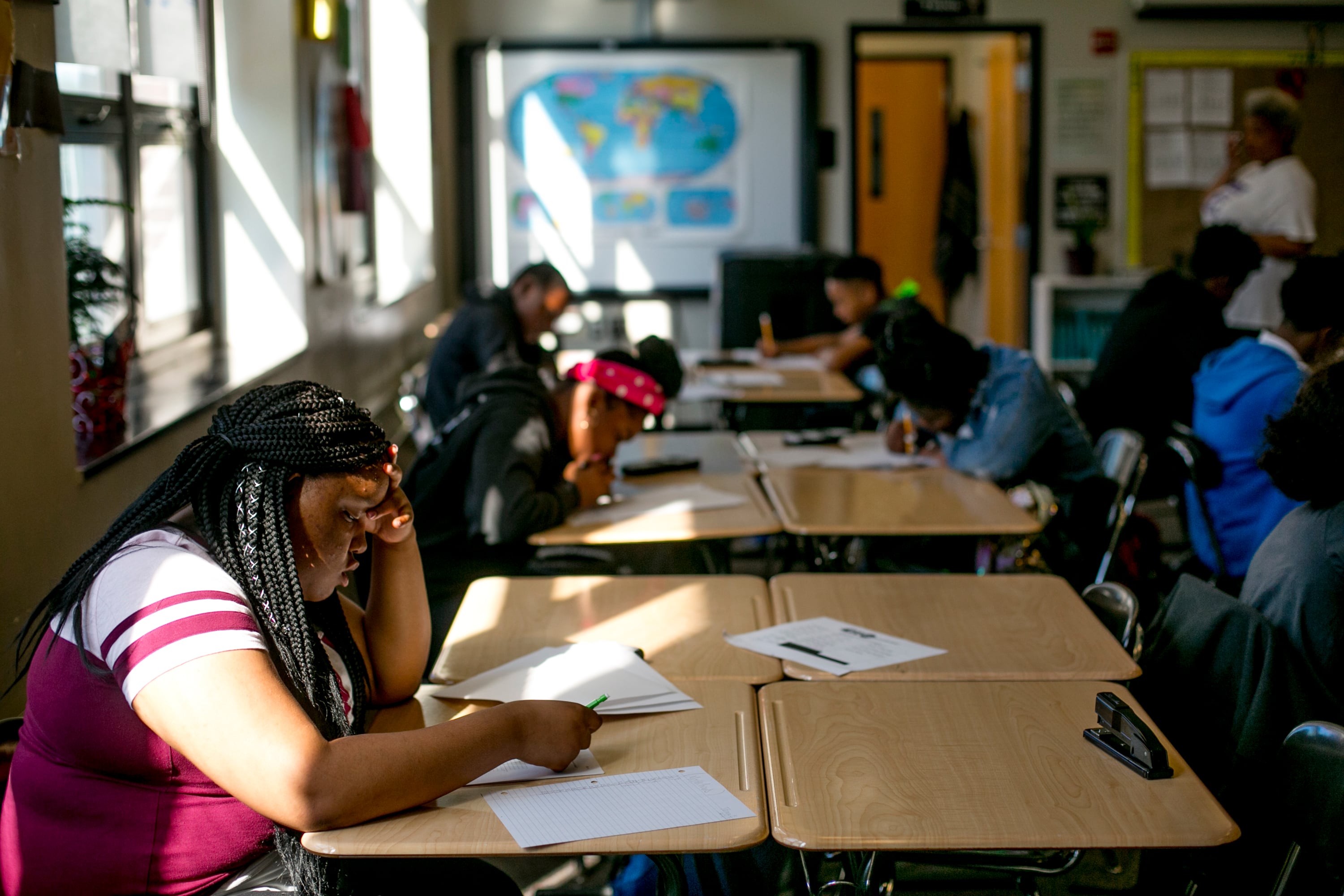

Seven decades after the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled racial segregation unconstitutional, students of color in Michigan continue to attend schools rife with inequities.

The Education Trust-Midwest released a new report Wednesday that draws attention to these “devastating inequities” and renewed calls for a more equitable school funding system in Michigan to address them. It launched a new data tool that lets viewers see how much their schools would be funded if inequities were addressed.

The group also launched a new campaign involving a coalition of leaders across the state to call attention to “decades of neglect to Black, Latino/a students, and students from low-income backgrounds,” the resources and support their public schools need, and also the “urgent need to address profound pandemic learning losses” that hit underserved students especially hard.

“The urgency is to save another generation of students, so they can compete in a global economy and achieve the American dream of a good quality of life,” said Alice Thompson, chair of the education committee of the Detroit NAACP and one of the chairpersons of the statewide coalition.

Among the dire findings highlighted in the report:

- Nearly half of Michigan students of color and two-thirds of all Black students attended schools in districts with high concentrations of poverty, where 73% or more of the students come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. That compares with 13% of white students.

- Michigan students in districts with the highest concentrations of poverty are much less likely to have highly experienced teachers who are, on average, more likely to be effective.

- School-age children across the state have lost roughly half of a grade or more of learning in math and reading since the pandemic started. In school districts that serve predominantly Black and Latino students and students from low-income backgrounds, such as Kalamazoo and Lansing, learning losses were dramatically worse.

- At the current pace of educational recovery, most students would need an additional five years to catch up in math. In reading, most Michigan students would need decades — well beyond their time in school — to be able to read at their grade level, according to research from the Education Recovery Scorecard.

- School funding disparities between wealthy and less-resourced schools make it harder for high-poverty districts to support their students’ educational recovery from the pandemic.

“Segregation in education is not only happening based on race, but also based on socioeconomic status, and very frequently at the intersection of both of those factors,” said Jen DeNeal, director of policy and research at the Education Trust-Midwest. “And we know that concentrated poverty in particular is a real challenge in Michigan.”

Schools with high concentrations of poverty, she said, tend to have fewer resources, less experienced teachers, higher teacher turnover, and increased exposure to environmental hazards and safety concerns.

Last year, the organization and others urged state lawmakers to adopt what they called an “opportunity index” that would provide additional money to districts serving communities with higher concentrations of poverty. The budget for this current year adopted that proposal, which has provided an additional $1 billion in funding to districts to serve at-risk students. But the opportunity index that went into effect doesn’t go as far as advocates wanted.

The Education Trust-Midwest’s new data tool will give families information that hasn’t been readily available. It shows them how much their districts are receiving now in per-pupil funding, including the additional amount they are receiving for at-risk students. A second column shows how much they would receive if the opportunity index was fully funded. And a third column shows how much districts would receive per student if they adopted a funding system similar to what Massachusetts adopted many years ago that has made it a leader in addressing funding inequities.

Here’s what the data tool shows for Detroit Public Schools Community District, the state’s largest district: DPSCD currently receives $10,862, including its basic per-pupil amount and its funding for at-risk students. If the opportunity index was fully funded, the district would receive $13,448 for each student. And if the Massachusetts funding model was used, the district would receive $17,881.

Lori Higgins is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at lhiggins@chalkbeat.org.