Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy.

About this series: Four years ago, Chalkbeat reporters documented the stories of high school freshmen experiencing a critical year through Zoom calls and from behind masks. These students, who experienced freshman year at a distance, are now graduating seniors. How did the pandemic shape their high school lives? How did their expectations for these formative four years play out? We caught up with these members of the Class of 2024 to find out.

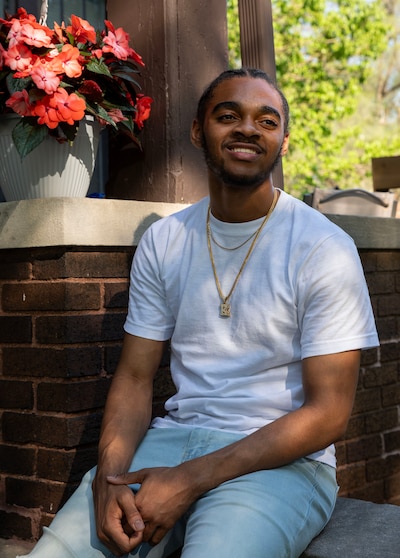

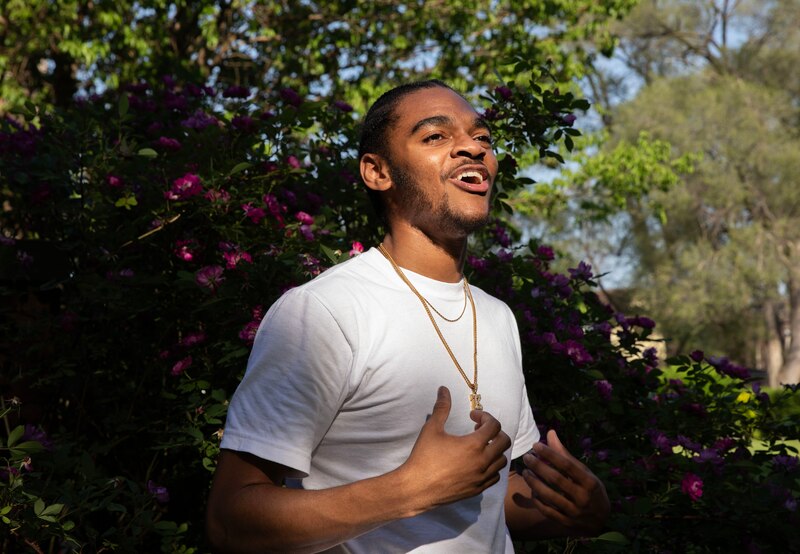

When King Bethel tilted his head back to sing during a recent performance at the Fellowship Chapel, the accompanying music didn’t play from the speakers. He had to think fast.

“I threw on my improv hat, my acting hat,” Bethel said as he snapped his fingers. That meant singing his smooth, honey-coated voice a cappella and drawing the crowd into an impromptu Q&A session about his work. When the music finally came on, he slipped into full performance mode.

“You know, I was having fun the whole time,” Bethel said. “I wasn’t stressed, I wasn’t concerned.”

For Bethel, that moment represented his growth as a musician and a performer. He has been acting, singing, and performing since he could walk. His music helped carry him through the pandemic, when COVID nearly took his mother’s life, when he practiced alone at home, and when he changed schools in hopes of more opportunity.

He has experienced far more stressful life events than a sound system mishap.

Bethel was among the millions of American high school students who spent their freshman year online. Now he is the senior class president and salutatorian at Jalen Rose Leadership Academy. In the fall, Bethel is heading to the prestigious Berklee College of Music in Boston.

He sees the pandemic as a defining moment in his life, one that challenged his strength and sharpened his understanding of the fragility of life.

Coming of age during the historic COVID pandemic

During the pandemic, Bethel’s mother, Netha Johnson, contracted COVID and battled the illness for weeks. As Bethel thinks back to that time, his playful demeanor shifts and his voice drops into a low, deep tenor: “She came in my room with this very blank face and her skin was extremely pale,” he said.

Johnson’s condition continued to worsen and her son was worried he might lose his mother. She has helped him at every turn to cultivate his passion for music and performing, from buying him a Fisher-Price toy keyboard when he was 2 years old to entering him in local singing competitions and chauffeuring him to performances all over the city.

His mom eventually recovered. While she was sick and as the pandemic raged on, Bethel distracted himself with his virtual classes at Detroit School of Arts, where he attended his first year of high school virtually and his second year in a hybrid format. Between classes and his after-school activities, he often had three devices connected to different Zoom meetings.

But he kept all the meetings, all the screens in order. He said the pandemic drove him to double down on his work and maintain his 4.0 grade average. He would spend hours plowing through his homework so he could devote the rest of his time to making music, singing, and getting in shape. During that time, he lost 60 pounds from his once 200-pound frame.

Some of the drive and ambition that helped Bethel excel in virtual classes and achieve personal goals stemmed from a need to escape the stress and uncertainty wrought by the pandemic. “It was too sad, it was too much,” he said.

For his junior year, Bethel transferred to Jalen Rose Leadership Academy, leaving behind the arts focus of his first school, because he said the charter school would connect him to more college scholarship opportunities. It was the first time in his high school career that he was taking all his classes in-person and he felt uneasy about it. Was it really safe to be in close proximity to his classmates?

The realization that Bethel was navigating a new normal was just one moment of discovery for the burgeoning Detroit performer. The pandemic also marked the point when he became more acutely aware of injustice.

“I started watching the news more, really paying attention to what was going on,” he said. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, Bethel led and spoke at a racial justice march, wrote a speech about redlining that he submitted to a national competition, and became involved in more community organizations. Now he is working with his father, Monty Bethel, to launch a nonprofit that will empower Black families to improve blighted neighborhoods in the city.

The contrasts he saw between Detroit’s suburbs and the city itself opened his eyes to the problem: “I don’t even have to travel far — Dearborn, Ann Arbor — to see the subtle differences in how the trees are grown and where they are, the outdoor placement of things, how the community works, how the schools look, how big the schools are, what extracurricular activities the schools have,” he said. “I haven’t seen an electric charging station yet in my community, but I see them all the time in suburban communities.”

A young Detroit performer who ‘could do anything’

This summer, Bethel will work at one of the music camps that helped him further his skills as a musician, the Keys 2 Life program. When Bethel was 11 years old, he met musician, educator, and preacher Darrell “Red” Campbell at the camp. Campbell was teaching a beat-making class and was struck by Bethel’s multitude of talents.

“He was a bit of a chameleon, like he could fit in anywhere,” Campbell said. The program includes classes in songwriting, beatmaking, dancing, and acting. Bethel was attending classes in the latter but Campbell said the student wanted to do it all.

“It’s wild that I even became his mentor — he wasn’t even in my class — but that speaks to him dabbling in a little bit of everything. And so, having one of the actors who can make beats, and then who can sing and all that, my first impression was like, he could do anything.”

Today, Campbell works with Bethel through the Hitsville Next Motown programs, where he produces some of the teen’s music. When Bethel first walked through the doors, he arrived “in competition fashion,” Campbell said. “He had his own beats, his own songs, and everything like that.”

The work that Bethel and Campbell have done together, and the work Bethel has done with a long list of community members over the years, culminated this year when he was accepted to Berklee. He had not even heard of the school until one of his mentors, Rashard Dobbins, of Class Act Detroit, told him about Berklee and a partnership Dobbins had with the school.

As prestigious as Berklee is, it was not Bethel’s first choice. He also applied to Juilliard and Yale but was rejected. It was a tough moment, but he is clear-eyed about stepping into an industry where the pathways are paved with rejection and the only way through is to keep moving. If music doesn’t work out, Bethel will study marketing and law.

“I have a backup plan but I’m not letting it take me away from Plan A, which is my music career and what I love to do,” he said. Whether through music or another industry, Bethel said his ultimate goal is to be an influential community leader.

Angela Kee recognized Bethel’s maturity and leadership early on. The choir teacher at Detroit Academy of Arts & Sciences began working with him when he was a fourth grade student there. “And he introduced himself like a little businessman. He extended his hand and said, ‘Hello. My name is King. And I would like to join your choir.’” Kee was stunned, all she could do was “a hard blink” at the fourth grader.

While King was a member of DAAS’ choir, it garnered multiple awards, including two Detroit Music Awards and a Michigan Emmy.

Kee has no shortage of stories that illustrate Bethel’s drive and resilience, like the time he tracked down billionaire Dan Gilbert during a field trip and introduced himself. “So you got the other boys running around, doing the arm farts where you put your palm into your armpit and you know, just doing goofy stuff. King’s over there … I saw him extend his hand to Mr. Gilbert and introduce himself. He said, ‘My name is King. And someday I’m going to be just like you.’”

That encounter was fruitful — in 2019, Bethel sang the national anthem during a basketball game when Gilbert’s Cleveland Cavaliers were playing.

Now, Kee said, she is enjoying a moment living vicariously through one of her former students. “Berklee was a school that I wanted to attend … because I knew that was the place to go for serious musicians.”

For Bethel, it’s sinking in that his acceptance to Berklee is a major feat. And he is quick to acknowledge the many people who helped him get to this point — family, mentors, community members, and a city with a rich musical legacy that gave the world some of his key sources of inspiration, artists like Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, and J Dilla.

The strange days of the pandemic figure prominently in his trajectory, too.

“That whole experience, and the aftermath, the healing from it, made me stronger. And it also made me love more,” he said.

Robyn Vincent is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit, covering Detroit schools and Michigan education policy. You can reach her at rvincent@chalkbeat.org