Nearly 1 in 3 K-12 students in Michigan missed 10% or more school days this past academic year, a tiny decrease from last year but still considerably higher than before the pandemic.

The troublesome trend comes as state test scores show students have still not fully recovered from the pandemic. Educators blame a host of factors, from poverty and health to transportation and accessibility of online course materials.

“It’s disappointing that we didn’t see the progress for this past school year that we saw the year before,” said Jeremy Singer, an assistant research professor at Wayne State University who studies student attendance.

“We know the fundamental reasons that kids miss school, so the question obviously is: What is the extra thing since the pandemic?”

Michigan defines chronic absenteeism as missing 10% or more of school days, or 18 days or more during a 180-day school year.

During the 2023-2024 school year, 29.5% of students were chronically absent, down from 30.8% the previous year.

That’s still significantly higher than during the last pre-pandemic school year, when 19.7% of K-12 students were chronically absent.

Poverty is a big factor, affecting parents’ ability to navigate illness, work, and get children to school. Districts with the greatest percentage of economically disadvantaged students have the highest rates of chronic absenteeism, and those with the fewest poor students have the lowest rates.

But almost every district in Michigan, wealthy or poor, urban, suburban or rural, absentee rates rose during the pandemic.

Chronic absenteeism rates vary among districts:

- Detroit Public Schools Community District: 65.8% during the 2023-2024 school year, up from 62.1% pre-pandemic.

- Grand Rapids Public Schools: 41.2%, up from 27.3%.

- Ann Arbor Public Schools: 38.1%, up from 13.3%.

- Bloomfield Hills Schools: 17.7%, up from 9.5%.

- Portage Public Schools: 16.5%, up from 10.2%.

Bridge’s analysis shows 40.1% of economically disadvantaged students are chronically absent compared to 16.1% of non-economically disadvantaged students.

Proficiency scores track both poverty and absenteeism, the data shows: For the 50 districts with the highest overall proficiency rates (over 60%) in English language arts for grades 3-8, an average of 16% students were chronically absent. They were also among the wealthiest districts — Northville, Birmingham, Forest Hills, and East Grand Rapids.

Overall, the 50 lowest-scoring districts, including Pontiac, Flint, and Muskegon, had some of the highest absenteeism rates, with an average of 54.7%. And fewer than 12% of students in those districts in grades 3-8 were proficient in English language arts.

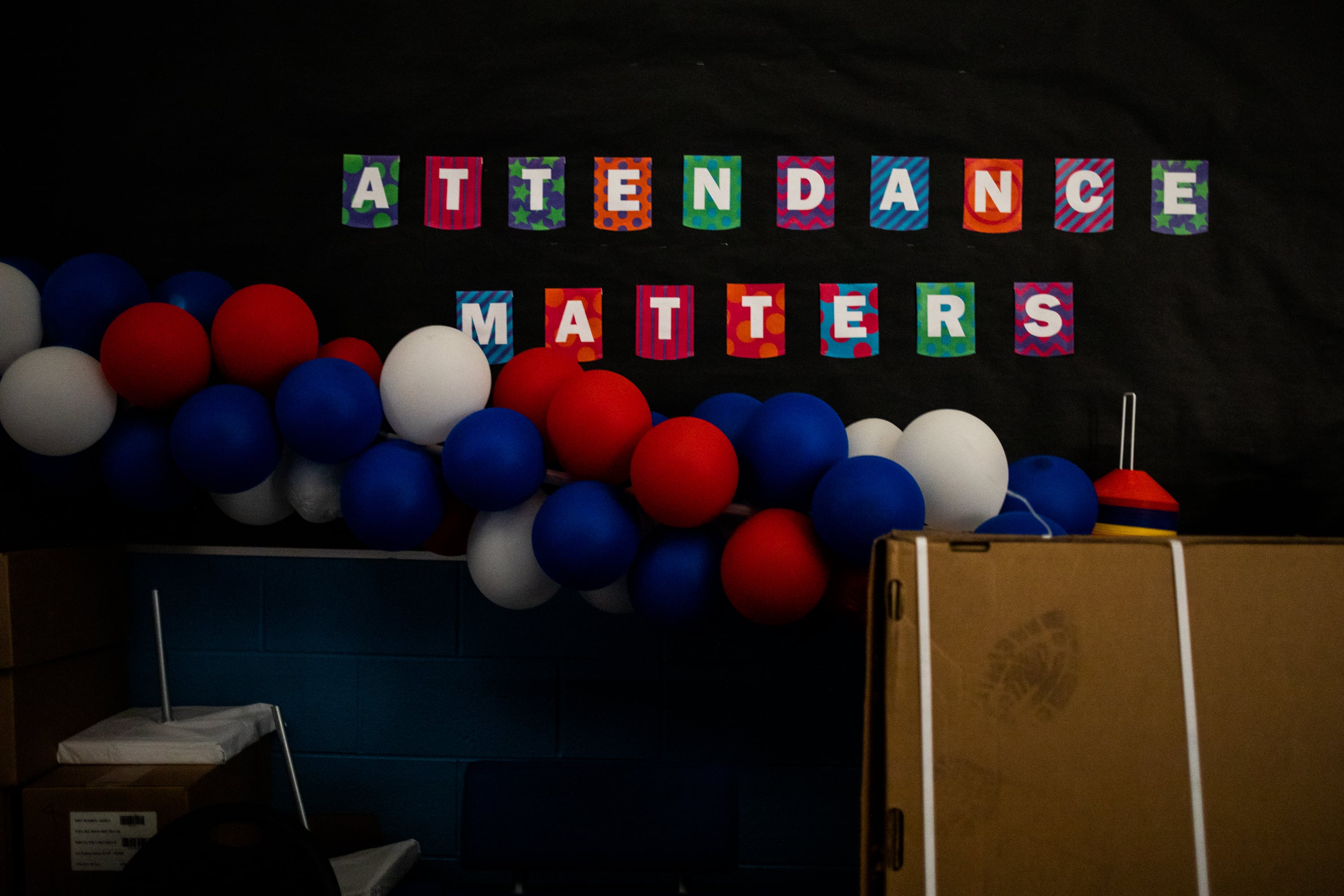

“Our students need to attend school regularly to maximize their school experiences,” said state Superintendent Michael Rice. “Despite our progress, far too many students are chronically absent. We need to work together to redouble our efforts and remove barriers to school attendance.”

Absenteeism is a national problem.

A Detroit News and Associated Press analysis of 2022-2023 data found that Michigan’s chronic absenteeism rate was the seventh highest across 45 states.

Chalkbeat reports 14 states are committing to cut their chronic absenteeism rate by half in five years.

Using federal COVID-19 relief funds, schools have invested in tutoring and other efforts to help students make up lost academic ground.

Marguerite Roza, director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University, a research center that explores education finance to inform policy, told Chalkbeat Detroit and Bridge Michigan last month that investments don’t work if students aren’t in school to use the supports.

Generally, “attendance matters for achievement,” Singer said.

“What is the relationship between attendance and achievement post pandemic? Is missing school worse for students? Is missing school not as consequential as it used to be?”

In Northview Public Schools in Grand Rapids, about a quarter of students were chronically absent last school year. That’s down from 41.1% students the previous year but still higher than 13.3% pre-pandemic.

Angela Jefferson, deputy superintendent, said it is the district’s role to ensure there’s a culture of belonging, so students want to attend school.

She told Bridge students are able to stay up to date with coursework when they are absent more easily than before the pandemic because of programs like Canvas.

“I think prior to the pandemic, if you missed school, you missed a lot of instruction, and certainly students in the classroom is a great priority,” Jefferson said.

But with programs where students can see their coursework online, “it’s a blessing and a curse because students could miss school and still stay very well academically connected.”

Jefferson and others acknowledge that factors outside of a school’s control also factor in student attendance.

At Westwood Community School District in Dearborn Heights, Superintendent Stiles Simmons said his district has experienced an uptick in student homelessness and people are “becoming increasingly transient.”

The district is working with Concentric Educational Solutions, which sends people to visit student homes and aims to discuss with students’ families about what’s stopping students from regularly attending class.

Simmons said the district tries to be responsive to what they hear from families about barriers to attendance.

If a student is missing transportation, the school can set up temporary transportation. If a student needs clean clothes, the family may be able to use the school laundry machines. If the student needs food, the family can stock up on food from the school pantries.

Detroit Public Schools Community District plans to add laundry facilities to every school in an effort to combat absenteeism, Chalkbeat Detroit reported this month.

Both Simmons and Jefferson say school choice policy may also be playing a role in attendance numbers.

Students who are not zoned for a particular school district may attend a different district but rely on their parents to get to school. If a parent loses reliable transportation or there’s bad weather, that can affect a student’s attendance for several days

Statewide, 1 in 4 students now attend a charter school or a district other than the one in which they live, a Bridge Michigan analysis last year found.

Isabel Lohman is a reporter for Bridge Michigan. You can reach her at ilohman@bridgemi.com.

Mike Wilkinson is a reporter for Bridge Michigan. You can reach him at mwilkinson@bridgemi.com.