This story was produced as part of a collaboration between Chalkbeat and Planet Detroit. Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy. Sign up for Planet Detroit’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with local environment and public health news.

In second grade, Joshua missed two to three days of school per month because of his asthma. He had to repeat the grade.

His mom, Mayra Hernandez, said Joshua was so embarrassed that he had been retained that he wore a hoodie “so that the other kids [wouldn’t] see that he was still in second grade.”

In Detroit, children have especially high rates of both asthma and absenteeism. Chronic absenteeism – when a student misses 10% or more of the school year – is a complex and pervasive problem nationwide, with a variety of causes.

More than 50% of the students who attend district and charter schools in Detroit are chronically absent. In the Detroit Public Schools Community District alone, the rate is nearly 66%. Asthma isn’t the only reason students miss school in the city, but its contribution to absenteeism fuels an attendance crisis that hurts students and their futures, disrupts school improvement efforts, and leaves a majority of students performing at extremely low levels and in a constant state of catch up.

“We know for sure that [asthma] can be one of the main reasons why kids miss school,” said Dr. Dee Poowuttikul, chief of the Children’s Hospital of Michigan’s allergy center in Detroit. “We can see it firsthand when school starts here in September, October — that’s usually the highest time when we have asthma hospitalizations.”

One in 10 Michigan students with asthma miss more than six days of school each year due to asthma, according to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Neither DPSCD nor any other government agency tracks how many school days students in Detroit miss because of asthma, however, making it difficult to understand the pervasiveness of the problem.

Rates of asthma are worse in Detroit, though, than they are elsewhere in Michigan. A 2021 state report showed 14.6% of Detroit children had asthma, compared to 8.4% statewide. This report also showed differences between Black and white adult residents of Detroit: The rate of asthma hospitalizations for Black residents was more than three times the rate for white residents.

Kids in Detroit also may face multiple barriers to getting the care they need to keep their asthma under control, including lack of access to health care, the cost of treatment and medication, and an inadequate understanding of the condition and how treatment should work.

Asthma gets in the way of school – and kids being kids

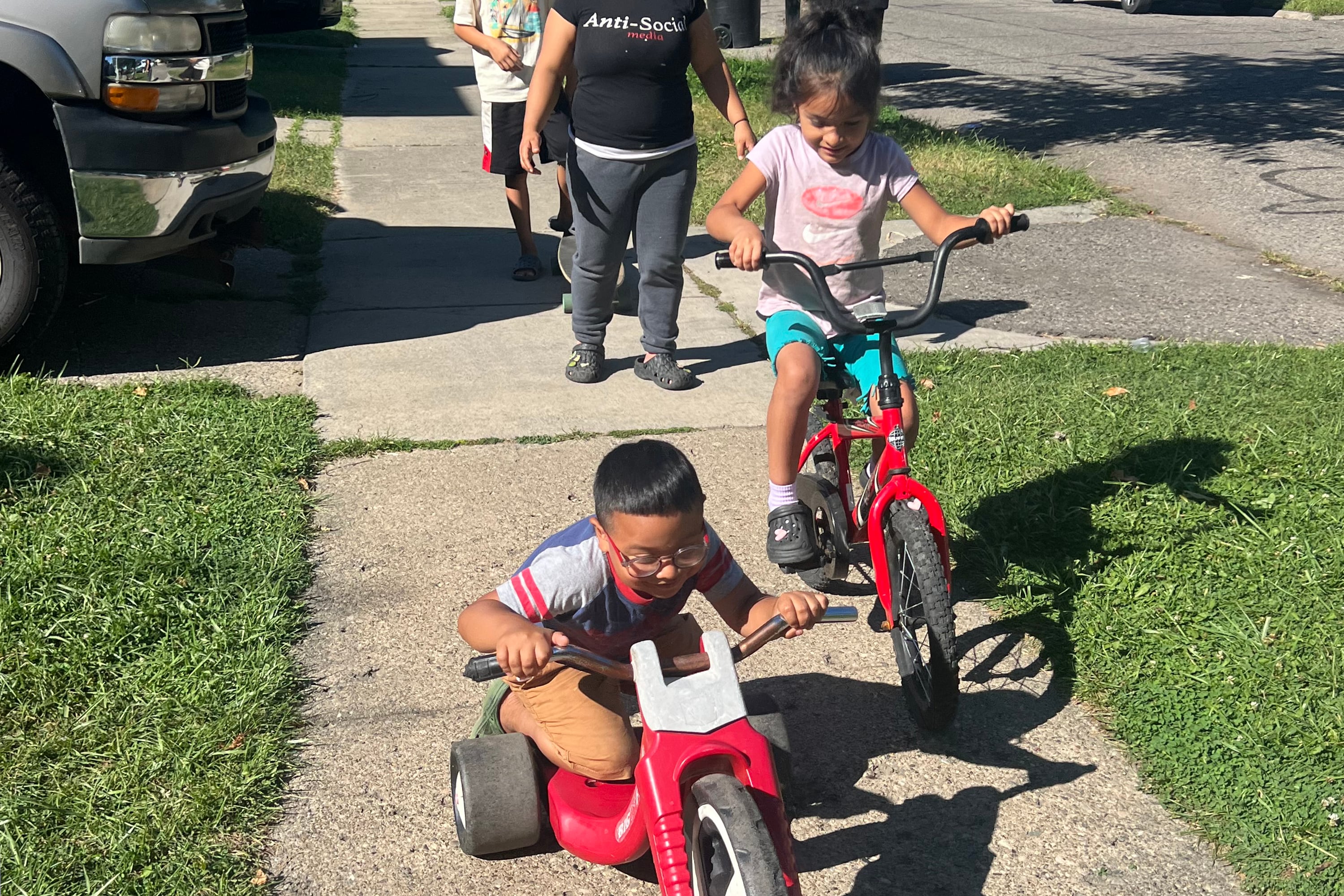

All three of Hernandez’s children have asthma and have missed school because of it, she said.

Five-year-old Gael loves to run around, but his asthma used to stop him. He would start coughing and need to sit down, and then his cough would linger, making it hard for him to sleep at night.

He missed half of his preschool year because he kept getting sick and his asthma would kick in. His asthma was more severe than that of his siblings. His 7-year-old sister, Dayami, didn’t miss much school because her asthma was easier to control. Now, thanks to health care providers who have pinpointed the appropriate treatment for all three kids, their asthma is under control, Hernandez said.

Now 10, Joshua is doing much better. But having to repeat second grade was difficult emotionally. “It was really hard because I had to support him and tell him, everything will be fine, you’ve gotta keep going,” Hernandez said. “And here he is now — he knows how to sing the happy birthday song in three languages ... I always tell him, ‘You’re gonna shine, regardless of if you’re behind a grade.’”

Many kids with asthma end up in the emergency room when the condition flares up. Such episodes can result in missed school and disruption for the entire family.

“The act of having to go to the emergency room is something that typically is at least a six-hour, eight-hour experience,” said Dr. Maureen Connolly, a pediatrician and the medical director of the Henry Ford Health School-Based and Community Health Program.

Hospitalizations may increase because kids get viruses that trigger their asthma, or because of ragweed allergies that are prominent in the fall, Poowuttikul said. Allergies often go hand in hand with asthma.

But the right treatment should prevent attacks, doctors say.

Two scenarios are common among Detroit kids with asthma: Child A has an asthma attack and goes to the ER. Child B starts to have asthma symptoms, like difficulty breathing, while at gym class, or playing sports. They stop their activity and their breathing later goes back to normal.

Neither scenario should be accepted as normal, doctors say. “You should actually be symptom-free if your asthma is well controlled,” Connolly said.

Many parents also think that if their kids have asthma, it’s normal for them to be wheezing, or to have an asthma attack, Poowuttikul said. But she explains to them: “I can get asthma to the point that they don’t have symptoms.”

Because of this gap in expectations, patient and parent education is key.

This involves helping people understand their disease process and how to mitigate their triggers, said Kathleen Slonager, a registered nurse and executive director of the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America (AAFA) Michigan Chapter. Often, no one has sat down with the patient and said, “Here’s what it is. Here’s how it presents. And here’s what you can do,” she said.

Hernandez’s three children were diagnosed with asthma when they were babies. But each needed different treatment.

“My kids are really active, so they couldn’t do much of activities like running, jumping, playing soccer — things they love to do — because their asthma was just attacking them,” she said.

Mi’Kah West is a senior at Cass Tech. When she joined the track and field team in middle school, she remembers needing to take more breaks than other kids, but she didn’t know why. At a doctor’s appointment when she was 13, her doctor diagnosed her with asthma. Now she plays lacrosse and, when she needs to, uses an inhaler.

“A lot of the girls on my team have asthma,” either sports-induced or set off by seasonal allergies, West said. “I wonder how many girls on my team when I did track and field in elementary and middle school had asthma, and I didn’t even know, because I didn’t know what that was, or I just felt like I was the only one that had that feeling.”

Sometimes, when patients go to the ER or urgent care for asthma, they’re sent home with what’s known as a “rescue” medicine.

But “rescue medicine is not a controller medicine — it doesn’t do anything for the inflammatory process of asthma,” Slonager said, adding that it’s important to help people “get the right medicine and take it the right way,” and understand what triggers their asthma.

Programs improve understanding of asthma, access to care

Both outdoor air quality and indoor air quality can exacerbate asthma — and many Detroit schools are located near highways, contain mold and mildew, or don’t have air conditioning, all of which can trigger the condition, Slonager said.

The Asthma & Allergy Foundation of America is working with partners to install air quality monitors in every zip code in Detroit, to “start tracking and trending what’s going on exactly, and how it impacts somebody with asthma,” she said.

Inside families’ homes, using air filters, replacing old carpets, cleaning up mold, and fixing leaks that can cause mold can help keep kids’ asthma from flaring up. AAFA’s HEAL (Health Equity Advancement & Leadership) Asthma program helps Southeast Michigan residents learn about their asthma, their disease process, and lifestyle changes that can help, Slonager said. HEAL provides some tools, such as air purifiers.

Having health care providers in schools can also make it easier for kids to get the asthma care they need. Every DPSCD school has a school nurse. About 90% of kids who go to the nurse can then go back to class, said Alycia Meriweather, DPSCD’s deputy superintendent of external partnerships and innovation. “The 10% of kids that don’t get sent back to class either go to the emergency room or they go home,” so more kids would miss school if they couldn’t see the nurse at school, she said.

Some Detroit schools house their own medical clinics. Henry Ford’s School Based and Community Health Program is a network of school-based and community clinics, including nine inside Detroit schools. These clinics provide integrated care, including primary and behavioral health care, to students and other young people from the community, ages 3-21, at no out-of-pocket cost, regardless of insurance.

Students may go to the clinic because they’re not feeling well, or because they need a physical or vaccines, for example. The clinics aim to “increase wellness in communities and also decrease absenteeism,” Connolly said.

The program sees 100-200 kids with asthma per year, Connolly said. If a student with asthma is having trouble breathing, they can get an albuterol breathing treatment at the clinic and avoid an ER visit. “Having those resources there can be really helpful, and it’s sometimes life saving,” she said.

The clinics collaborate with Henry Ford’s pharmacy. “We can order the medications and have them delivered to the school on the day of the visit,” and at no charge, Connolly said.

At some schools with these clinics and other school-based health centers, DPSCD has begun opening Health Hubs that expand the services offered. This includes a family resource distribution center to help meet basic needs, such as shelf-stable food, and a full-time navigator who helps families address their challenges. “The overall goal of the Health Hubs is to create a tangible, visible response to helping families address barriers that they face,” including asthma, Meriweather said.

Last year, Heath Hubs opened at five schools, and three more will open this year, she said.

Poowuttikul said she’d like to see stock inhalers in schools. Students often have their own inhalers at school, but many schools don’t have inhalers on hand in case someone has an asthma attack and doesn’t have theirs.

It’s similar to having automated external defibrillators, or AEDs, available places like airports, in case someone has a heart attack, she said. “There has been some discussion in medical societies for schools to have this kind of stock albuterol inhaler.”

Twenty-four states have laws or state administrative guidelines that allow schools to stock quick-relief medications for students with asthma. Michigan is not one of them.

Some kids with asthma are getting some treatment but not what they need to keep it under control. “People with asthma should see a specialist at least twice a year,” Slonager said. Asthma specialists, usually called allergists, can provide a baseline management plan and share it with the primary care doctor, she said.

Pediatricians sometimes refer children with asthma to Children’s Hospital of Michigan’s allergy center, where they can get more specialized care. Many families are seeking “medication that they might not be able to access, or getting allergy testing to identify triggers for asthma,” Poowuttikul said. Some newer medications for asthma, like biologics, usually require a specialist’s care, she said.

“The important thing to treat asthma is to prevent asthma,” Poowuttikul said, adding that identifying triggers and learning how to avoid them and use medication properly can control symptoms, so that patients get to what she calls an “asthma remission.”

“It is possible to be in remission for asthma [through] allergy shots and allergen avoidance, and at some point, certain patients might not need to be on daily medication,” she said.

Joshua’s asthma often flares up when the weather changes. So when it does, Hernandez said, “I know I have to be ready with the albuterol and the nebulizer. And in case he’s still having trouble, then I will contact his doctor.”

Hernandez relies on Children’s Hospital to keep her children’s asthma at bay, and that includes medication for seasonal allergies. “Sometimes having great medical support, it’s good because then they’ll be able to tell, OK, that treatment didn’t work, and we have a plan B where we can try an alternative medication. . . . If that helps, then we stick to that plan,” she said.