Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy.

Black children and students attending schools in Michigan’s poorest communities are more likely to be taught by less experienced teachers, according to a study that explored the many ways that ongoing teacher shortages affect the state’s most vulnerable students.

An analysis released Tuesday by the nonpartisan research and advocacy nonprofit Education Trust-Midwest found that students in these groups are more likely to be taught by teachers with emergency credentials and educators teaching outside of their fields of study. The districts with the highest concentrations of poverty in the state also struggle significantly more than wealthier school systems to attract and retain experienced teachers, the report says.

The analysis provides a more nuanced picture of the teacher shortage that has affected districts all over the state since the COVID pandemic. It shows that “everyone really is not struggling equally,” said Jen DeNeal, director of policy and research at Ed Trust-Midwest.

The researchers focused on inequities in the distribution of highly qualified teachers, because years of research shows that educators’ impact can be more powerful than any other factor in schools in determining student achievement.

“Teacher shortages make up one important component of opportunity gaps that then turn into achievement gaps,” DeNeal said. “And we know that these gaps result in discrepancies in reading and math proficiency based on factors like race and socioeconomic status.”

In addition to student racial demographics, the analysis uses the state’s six opportunity index “bands” to analyze teacher distribution. Districts are assigned to one of the six bands based on the percentage of students from economically disadvantaged families, and receive corresponding supplements to their funding.

The report also included input from focus groups of teachers from across the state.

What did the analysis find?

- In the state’s highest-poverty districts, more than 16.5% of teachers taught outside their own field of study in the 2022-23 school year. That was more than double the state average.

- Districts in the most impoverished communities were 16 times more likely to have teachers with emergency credentials — meaning people who are either substitute teachers or are working toward getting their teaching license.

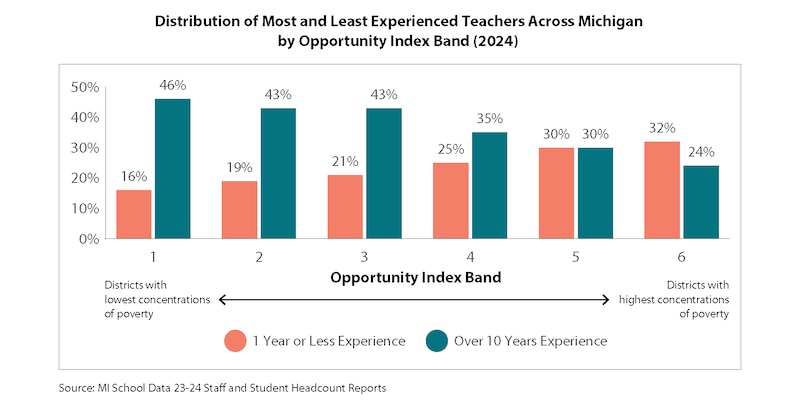

- First-year teachers made up 32% of all teaching staff in the schools in the state’s highest-poverty communities, compared with 16% in wealthier districts. In high-poverty districts, 24% of teachers had more than 10 years of experience, compared with 46% of teachers in wealthier districts.

- School systems serving majority Black student populations were nearly four times more likely to learn from educators teaching outside of their fields of study than students in primarily white districts. Those students were also nearly twice as likely to learn from a teacher with fewer years' experience, and four times more likely to learn from a teacher with emergency credentials.

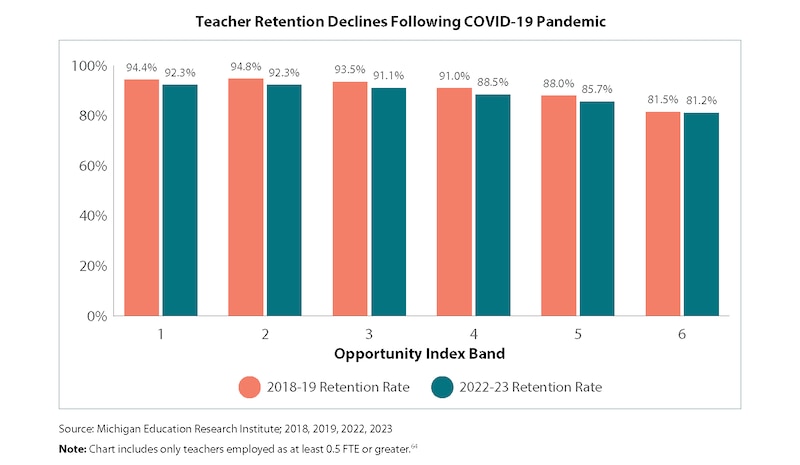

- While all districts had a harder time retaining teachers in recent years compared with before COVID, retention rates in more impoverished districts were 11 percentage points lower than in the wealthiest districts in 2022-23.

What does the report suggest to improve teacher equity?

The researchers credited Michigan with making “significant efforts and investments” to address the problem through innovative programs like the MI Future Educator Fellowship and the MI Future Educator Stipend, along with mentoring and induction programs, and a state funded student-loan repayment program.”

Recent efforts also include allowing some districts to use some funds dedicated to at-risk students to attract and retain teachers.

Meanwhile, low teacher salaries remain a big challenge for urban districts to compete for talent.

“Why would you go and spend $50,000 to $80,000 to go in student loan debt to become a teacher when you qualify for the Bridge Card?” one teacher said in a focus group for the analysis, referring to eligibility for Michigan’s food-stamp program.

The report recommends that the state address this need by making school funding more equitable.

“Most urban public schools do not have the funds to increase pay immediately,” Kyle Lim of the Grand Rapids-based racial justice organization Urban Core Collective, said in a statement. “As a state, we need to pressure our legislators to increase education revenue for schools.”

Michigan legislators passed a historic budget in 2023 that benefited students in the most need. Advocates, including Ed Trust-Midwest, said at the time that this type of increase in funding would have to continue for decades to make real change.

In the 2024-25 school budget, per-pupil funding did not increase, but the state did increase the opportunity index funds.

With Republicans now in control of the state House and more friction in the legislature, it’s unclear whether future state school budgets will include the same priorities.

DeNeal said there are “positive signs” both sides of the aisle will support more increases in funding for at-risk students, citing bipartisan support last year for legislation to require the “science of reading” in early literacy learning.

The opportunity index “has widespread benefits for every geographic area, and, frankly, every legislative district in the state of Michigan,” she said.

The report also recommends improving data collection to better understand why teachers are leaving the field; investing and prioritizing support for administrators; and increasing access to high-quality professional development.

Maegan Frierson, director of system building at the Kent County education network K-Connect, said the teacher shortage isn’t something schools can “hire their way out of.”

“If we’re wanting folks who will have the greatest impact on our kids, we have to have supportive environments,” she said.

The West Michigan Teacher Collaborative, for example, sees success with sessions that connect future educators with current teachers, Frierson said.

“They are having conversations with experts from the community and getting advice from leading educators,” she said.

Hannah Dellinger covers K-12 education and state education policy for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at hdellinger@chalkbeat.org.