Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy.

A first-of-its-kind report says Michigan’s K-12 school buildings need $23 billion of work over the next decade — a dire situation that some superintendents said should prompt urgent policy discussions at the state level.

A large chunk of that dollar amount, $10.9 billion, is for basic needs such as repairing HVAC systems and roofing.

“Students deserve to learn in schools that ensure basic safety, health, and wellness standards are met,” Kenneth Gutman, superintendent of the Oakland Schools intermediate school district, said during a media roundtable Thursday. The study, he said, “tells us we are a long way from our schools meeting those basic standards.

But Michigan does not provide direct funding to schools for facilities. Districts must seek voter approval for funds to improve buildings and make major repairs.

“We know what the facility needs are, and so now we have to decide as a state, what do we want to do?” Gutman said.

The study was completed by the School Finance Research Foundation, which was created after state lawmakers called for a comprehensive report on the true cost of meeting basic K-12 education needs. The foundation has previously released studies showing what it costs to educate students — and the prevailing inequities in Michigan’s school funding system. Some of its findings have already prompted action by state leaders, including a system created under Gov. Gretchen Whitmer that provides more funding to districts for the most vulnerable students, including those from low-income homes, students with disabilities, and English language learners.

This is the first time this group or anyone else has done such a comprehensive study of school buildings in the state. It doesn’t include the state’s nearly 300 charter schools, though, in part because most of their buildings are privately owned. The study also did not include school district administrative buildings, athletic facilities, and other district-owned facilities that don’t provide direct instruction to K-12 students.

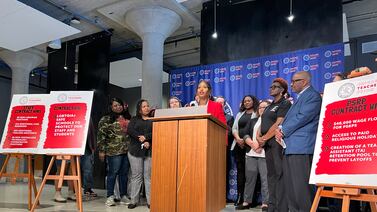

During Thursday’s roundtable discussion, superintendents of seven intermediate school districts across Michigan spoke of the facility needs.

In rural and northern Michigan communities, districts have had to defer maintenance work, because it is becoming harder for them to pass bond proposals to fund facility improvement projects, said Nick Ceglarek, superintendent of the Northwest Education Services.

Meanwhile, the costs of upkeep keep growing. “As school districts defer replacement of these key systems and patch them and patch them and patch them, that really just increases their operating costs and takes more money away from the instructional process,” said Steven Ezikian, executive director of the research foundation.

The facility problems create inequities, superintendents at the roundtable said, because school districts in wealthier communities with higher property values can afford to raise money to fix buildings through voter-approved bond proposals, while less wealthy communities struggle.

As part of the study, which was conducted over two years, the research team evaluated 2,534 buildings in more than 500 school districts to determine the cost of having them meet health, safety, and wellness standards, said Steven Tunnicliff, superintendent of the Genesee Intermediate School District.

Engineers studied 89 individual components of a school facility, including HVAC, ventilation, lighting, electrical, fire alarms, plumbing, fire protection, foundations, staircases, elevators, and kitchens, Tunnicliff said.

For the most part, Ezekiel said, schools “have been doing a good job maintaining their buildings. We’re not looking at situations, for the most part, where buildings are falling apart.”

But they encountered a handful of buildings that were over 100 years old, and a number of buildings that were built before 1970.

The big concern raised in the study is whether schools will be able to address their facility needs over the next decade. That may be particularly important given the potential cuts to federal funding. The Trump administration and the Republican-controlled Congress seem determined to reduce spending across the board, including funding that supports education. It’s still unclear, though, how much of those cuts schools will have to deal with.

“The question is, how can we continue to support and elevate the level of funding in Michigan to properly and appropriately educate each of our scholars across this great state,” said Daveda Colbert, superintendent of the Wayne Regional Educational Service Agency.

Lori Higgins is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Detroit and writes about Detroit schools. You can reach her at lhiggins@chalkbeat.org.