Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy.

In a slightly warm classroom on a sunny April afternoon, five fifth graders loudly clapped their hands together or on their desks as they read a sentence out loud.

“Did” Clap. “She” Clap. “Wink” Clap. “At” Clap. “Hank” Clap.

With each clap, the students at Mark Twain School for Scholars in Detroit were distinguishing between the different sounds they were hearing with each word in the sentence, a common exercise in literacy lessons on phonological awareness.

They quickly moved to the next sentence, and Kimberly Sommerville, the academic interventionist who works closely with them to improve their literacy skills, immediately spotted a problem.

One student read the sentence, then the other four students were expected to say, and clap, what they heard. But the students were clearly hearing “A lot of junk is in the sink.”

“Listen,” Sommerville interrupted, then enunciated each word loudly for the group, helping them hear that the last word was supposed to be “tank” and not “sink.”

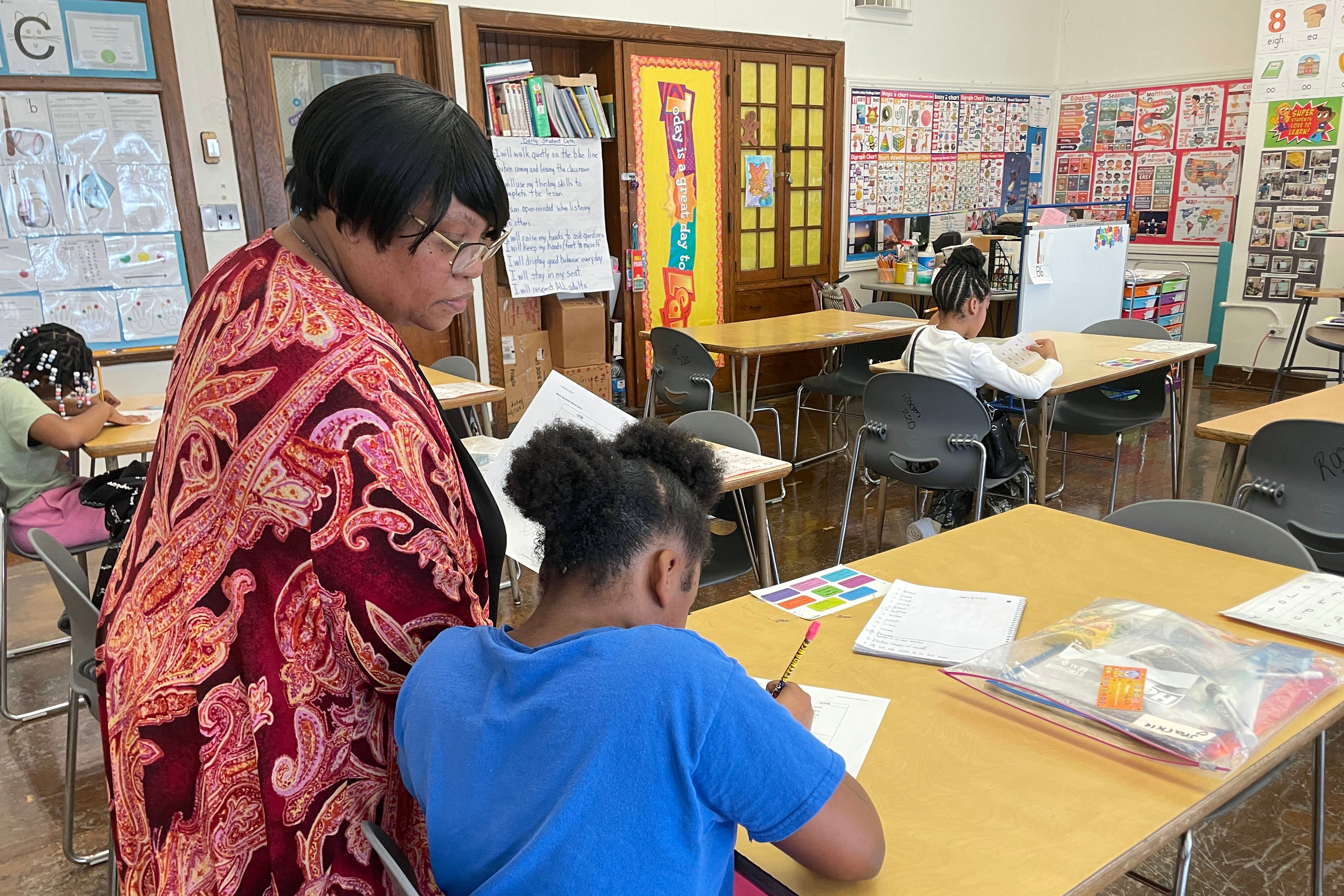

Scenes like this happen across the Detroit Public Schools Community District and are led by academic interventionists like Sommerville, whose work is a vital part of the district’s effort to improve academic achievement and get struggling students like the five in this classroom back on track. She is one of 600 such interventionists that the district employs. Their role existed before the pandemic, but the district has invested even more in them to address the learning loss students experienced during the public health crisis.

It’s “the best program ever,” Sommerville said, because of its strong focus on phonics and its use of the Orton Gillingham method, a popular approach to teaching reading. But she worries about its future because it partly benefits from federal education funds that are at risk of being cut. (Money from the settlement of a literacy lawsuit and a grant from the MacKenzie Scott Foundation also cover the cost of the academic interventionists.)

Sommerville has reason to worry, as do educators across Michigan whose schools rely on federal funding. The Republican-controlled Congress has signaled that it plans to substantially cut federal dollars for public schools. The Trump administration has threatened to withhold federal funding from schools if they allow transgender girls to participate in girls’ athletics — already, it has moved to strip Maine of its funding for refusing to comply. The administration also has threatened to withhold federal funding from states that don’t eliminate diversity, equity, and inclusion programs in schools. (Those efforts hit a legal roadblock Thursday.)

Republican proposals could affect Michigan students in myriad ways, from early childhood to tutoring to accessing school meals. Trump has proposed eliminating Head Start, a long-running early childhood program for children from low-income homes. Republican lawmakers have pitched changes to federal school meal programs that could leave hundreds of thousands of students in Michigan without crucial breakfasts and lunches. Deep cuts in the U.S. Department of Education, part of Trump’s efforts to eliminate the agency, have affected services for some of the most vulnerable children. Deep cuts in AmeriCorps could also be felt locally, particularly for a statewide tutoring program that helps students at about 80 schools in Michigan. And Trump’s tariffs could increase costs for school districts.

In Glen Lake Community Schools in northern Michigan’s Leelanau County, district officials fear the district could lose nearly $3.3 million in federal impact aid that it receives to offset the loss of property tax revenue from Sleeping Bear Dunes national lakeshore, which is located within the district’s boundaries. The impact aid provides operating funds for the district and makes up 20% of the district’s budget.

Glen Lake Superintendent Jason Misner said the proposed cut could be absorbed by the district’s healthy fund balance for the next school year. But there are limits to how far that rainy day money can go.

The uncertainty weighs on school district leaders who must build budgets for the 2025-26 school year by the end of June with little concrete information about how much federal funding they’ll receive, or if they’ll receive any. And teachers don’t know yet what potential cuts will mean for them in the classroom.

“Every day I’m scared,” said Janine Scott, a math lead teacher at Davis Aerospace Technical High School (and a member of Chalkbeat’s reader advisory board), during a recent panel discussion on teacher morale. “We have kids who rely on [federal funds].”

The unpredictability “creates anxiety, and anxiety within our school administration and support staff” creates more concern,” said Nick Ceglarek, superintendent of the Northwest Education Services, an intermediate school district that provides services to local schools in Antrim, Benzie, Grand Traverse, Kalkaska, and Leelanau counties. Many of those services, including some that provide direct instruction and help to students, rely on federal funding.

There are few answers to anxious questions

On an evening in mid-March, more than 1,000 people logged into a virtual engagement session with DPSCD Superintendent Nikolai Vitti to hear about the potential cuts and their impact on the district. Those attending peppered Vitti with questions about whether nurses, central office staff, special education staff, and others would be affected. Some wondered if class sizes would rise, whether there would be funding for school lunches, and whether paraprofessionals could lose their jobs.

There were few concrete answers because so little is known about what might happen.

Federal funds touch many aspects of education. Among the most common: Title I funding helps schools provide support to students from low-income homes. Title II funding provides money for teacher training and other initiatives on effective instruction. Title III money invests in English language learners. Title IV supports programs that provide educational enrichment for students from low-income homes. Schools receive Medicaid reimbursements for some students’ special education services. And the federal school lunch program allows all students in a school with a large number of students from low-income homes to receive free school meals.

The stakes are particularly high for DPSCD, the state’s largest district, as about 32%, or $210 million, of its annual budget comes from federal funding. In the virtual session, Vitti shared how a 25% cut — which hasn’t been proposed but is something a national urban schools’ group has suggested might happen — would affect the district.

Whatever cuts happen, Vitti said the district might be OK for the next school year if it uses its fund balance and state funding increases at the level Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has proposed. Other strategies to address potential funding cuts include accelerating the closure of schools the district is currently phasing out, reducing discretionary funding, freezing vacant positions, decreasing operating costs, decreasing the frequency of technology refreshes, and reducing insurance coverage.

But he strongly urged those in attendance to reach out to state and federal lawmakers to share their concerns and ask them to fight back against the potential cuts.

“This current president and administration is not supportive of our children and our communities based on their budget. Budgets define your priorities, period,” Vitti told those in attendance.

The possibility of federal funding cuts was the talk of a recent superintendent’s meeting for the school districts that are part of the Northwest Education Services.

Like most intermediate school districts in Michigan, the agency provides a range of direct services to students. Ceglarek, the superintendent, said he’s particularly concerned about proposed cuts in Medicaid funding.

Ceglarek said schools rely heavily on Medicaid dollars to provide services to students from low-income households and students who have individualized education programs, or IEPs, which spell out what services schools are required by law to provide.

“When a student has an IEP, we are obligated as a district to ensure that plan is enacted and those services are provided, whether we get funding for it or not,” he said.

The ISD receives more than $2 million in Medicaid reimbursements, which is used to hire speech and language pathologists, psychologists, social workers, and physical therapists and then “deploy them into our local districts to provide these needed services.”

“It’s quite an efficient model,” Ceglarek said. “Many of our districts … don’t necessarily need a full-time speech pathologist. They may only need a half-time person.”

He has the same concern about any potential cuts to federal migrant student funding, because the ISD hires a specialist who travels among the districts and provides a range of services to English learners.

“Should those dollars be eliminated … That’s a scary proposition,” Ceglarek said.

‘You want your kids to do well in life.’

“Are you ready?” one girl standing at the front of the classroom at Detroit’s Mark Twain school said to her peers. When they all said yes, she began reading sounds such as “ing,” “sp,” “a,” and “wh.” With each sound, the students wrote what they were hearing onto a dry erase board then held it up when they were done.

After a few exercises led by Sommerville, she turned it over to her students to guide their peers. Having students lead an activity isn’t part of the academic intervention program, but it’s something Sommerville began doing because students expressed an interest.

“To me, they take ownership of the program,” Sommerville said. They do so well that when Sommerville’s coach visited her classroom two months ago, she joked that, “you’re not going to have a job.”

Sommerville is trying to remain hopeful that the Trump administration won’t make substantial cuts to education.

“I think he’s just being spiteful right now, but I don’t think he’ll do that. Because you want your kids to do very well in life. You really do, and that looks bad on him if you cut education. This is a representation of you, you know,” she said.

A little over a mile away from Mark Twain, at Ralph J. Bunche Elementary School in Ecorse Public Schools, similar literacy interventions were taking place as Marcie Gould, a tutor/interventionist, worked one-on-one with a struggling third grader.

After doing a warm up activity, Gould, who wore a black shirt with “literacy and justice for all” written in colorful letters, pulled out a set of small tiles and laid them out in front of the girl.

“We call these letter tiles so it helps the kids have a more hands-on experience,” Gould said of the tiles, each of which had different sounds that she moved around to create words and asked the student to read out loud.

The Ecorse district uses state early literacy grant dollars to pay for tutors like Gould from the Michigan Education Corps. But the program could still be affected by federal cuts. The Michigan Education Corps program is part of AmeriCorps, a federal initiative that has undergone significant cuts since Trump took office.

Ecorse Superintendent Josha Talison said that if any facet of the program had to be altered because of funding cuts, he would be concerned.

“Because the program has aided in the reading comprehension growth of our students since the program has been in place over the last five or six years,” he said.

Holly Windram, executive director of the Michigan program, said a continuing budget resolution Congress passed March 14 keeps their funding stable through the 2025-26 school year for the 80 or so schools that will use corps tutors. After that, there is uncertainty. Federal funding makes up 20% of its budget, and if that funding is cut for the 2026-27 school year, she’ll need to seek other sources of money.

“We financially have diversified funding. I’m concerned, but I’m not panicking financially at this point. My question is who are we going to get our money from,” Windram said.

Lori Higgins is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at lhiggins@chalkbeat.org.