(This story is one in a series exploring the basics of key issues in education in Indiana. For a list of the issues and links to the other stories in the series, go here.)

There is perhaps no more difficult and complicated issue in education than paying for schools, and Indiana in 2015 renewed its debate about how its funding system should work.

Republican leaders, who controlled the state legislature, promised an overhaul aimed at making funding more fair.

But even defining “fairness” got tricky, as school leaders with different challenges in urban, suburban and rural communities worried that somebody else’s gain from any change to the state’s calculation method could mean less money to educate their students.

Since 2009, Indiana has been reshaping its school funding system.

In the name of tax relief, the system was completely redesigned that year, giving the state a bigger and more direct role in managing the process of paying for public education.

But nagging questions about fairness have continued. All types of districts — cities, suburbs and rural areas — have complained that they are treated unfairly.

Changes in recent years have solved some problems, like scrapping a system that sometimes led to big swings in home property tax bills, but created others, like caps on property tax revenue that have put some districts in a bind to pay for basics like busing kids to school.

Indiana has always spent more to educate poor children, but an ongoing debate has centered on whether the difference in state aid between the poorest and wealthiest school districts is too great or too small.

A landmark court case

Indiana was one of the last states to receive a court ruling on the constitutionality of its school funding system in 2008. It was on the tail end of a decades-long national movement of lawsuits challenging more than 40 states by arguing they failed to fulfill their constitutional promises to to fund schools adequately and equitably.

Indiana’s Supreme Court case, Bonner vs. Daniels, was a win for the state.

The lawsuit charged that Indiana had failed to maintain a basic level of quality in schools, but the court said no such promise existed in the state’s constitution. The justices wrote:

“Although recognizing the Indiana Constitution directs the General Assembly to establish a general and uniform system of public schools, we hold that it does not mandate any judicially enforceable standard of quality, and to the extent that an individual student has a right, entitlement, or privilege to pursue public education, this derives from the enactments of the General Assembly, not from the Indiana Constitution.”

A move away from property taxes

Since the 1970s, Indiana has relied less on local property taxes to fund schools than neighboring states, with the state funding a larger share through sales and income taxes than many states that base their systems primarily on local property taxes.

In the 2000s, Indiana’s state share of general fund dollars to pay for day-to-day operations of schools — such as salaries for teachers and other school workers, equipment like computers and supplies needed to run the schools — had grown from about two-thirds to roughly 85 percent. Just 15 percent of local general funds for schools were paid by property taxes before 2009.

But a change in the law took local property taxes out of the equation entirely when it came to funding the day-to-day expenses of schools. Some local property taxes were still collected to help schools pay for transportation or buildings. Schools could still ask voters to raise local property taxes for extra operating money, but most haven’t asked.

As part of the shift to state funding of school operations, Indiana increased the state sales tax to 7 percent from 6 percent and touted the new system as tax relief for homeowners. But when a recession hit at the same time, causing sales and income tax revenue to drop, the state budget was soon stressed, and schools were among the services that saw funding cut.

As of 2012, U.S. Census data showed that just two states had a greater percentage of school spending coming from the state rather than local, federal or other sources than Indiana’s 51 percent. Only five states relied less on local taxes to fund schools. But Indiana also spent less per student on education than the U.S. average, ranking 28th nationally, according to the Census. Of the four states that border Indiana, only Kentucky spent less per student.

Lawmakers cap property taxes

In 2010, school funding was complicated some more by an effort to make property taxes, which sometimes shifted up or down unexpectedly for homeowners when their home values changed, more stable. The legislature’s solution was tax caps: homeowners now can’t pay more than one percent of the total assessed value of their property in property taxes. So if a home is assessed at 150,000, the residents won’t pay more than $1,500 in property taxes.

But while this stabilized tax bills, it made funding for some school services that still are paid by property taxes, such as transportation, less stable.

Before the change, the tax rate rose when the assessed value of a home dropped, so schools and local governments could still collect the same amount of money. But with the tax caps, the tax rate is now fixed at one percent. The limit means that revenue might fall behind what schools and government need to support the services they pay for.

For example, some districts are using property taxes to pay down debt for school buildings they’ve constructed. For those districts, debt service might eat up a greater portion of the property taxes collected, leaving less to pay for other services, such as busing children to school.

When a district in that situation hits the maximum amount it can collect in property taxes, money can run short as expenses still grow. Costs go up, for example, to buy new buses, repair older ones and pay bus drivers.

When that happens, schools face difficult choices. They can pay for busing by making cuts in other areas, or they can ask voters to approve an additional local property tax hike through a referendum. As a last resort, some districts have cut back transportation services, reducing or even seeking to eliminate buses to bring children to school.

Extra funding for poor, special needs

Since the Republican Party took control over both houses of the Indiana legislature in 2010, and then increased those majorities into supermajorities in 2012, lawmakers have increasingly raised questions about the proper level of extra funding to districts with large numbers of poor children.

The legislature eliminated several programs that tended to provide high-poverty districts with extra money. Some examples include extra aid districts once received to soften the financial blow when enrollment dropped and a guarantee that districts would receive no less than the amount they received the prior year.

In 2013, those changes extended to the primary method of providing extra money to educate poor children.

Indiana’s funding formula starts out by establishing a basic state aid amount to pay for each student’s education. But districts that have children who are poor or have special needs, such as disabilities, then get extra aid to help pay for those costs.

The state uses a complicated calculation to determine how much extra each district gets for these children, called a “complexity index.” The most important factor in the index was the measure of poverty: how many children qualify for free or reduced-price lunch under federal guidelines. To qualify for the lunch program in 2015, for example, a student’s family of four must have annual income of less than $43,500.

However, that changed for 2015 calculations. Extra aid for poor children will be calculated based on how many children receive welfare services or are in foster care, rather than the number of children who qualify for the federal free lunch program.

Supporters say basing aid on welfare or food stamps, which requires families to fill out additional paperwork, could be a more accurate measure of which families are truly poor. Some lawmakers have said they feared the federal free lunch program is more susceptible to fraud.

But districts with large numbers of poor children call the new approach a burden. They argue families that have already qualified under the federal free lunch program should automatically count as poor. They fear the new process will mean fewer poor families will be counted, robbing school districts of state aid they need to educate their children.

Trying to define funding ‘fairness’

At the core of the debate about funding in Indiana is a question of what “fair” funding should look like.

Does “fair” mean roughly equal, that each school district should get about the same amount of money per student?

Or should “fairness” factor in the real costs schools face to adequately prepare students for college or jobs, which might be different in each school district?

For decades, Indiana and other states have struggled with that question, sometimes tilting school funding systems more toward even shares for every district, while at other times focusing more money on districts perceived as having greater needs.

But the balancing act is never easy.

For example, if the state defines fairness in a way that assumes, and accounts for, higher costs in districts where more children are disadvantaged by the difficulties of growing up in poor families, how much more should it direct toward those children to even the playing field?

And what if the true cost of a level field is so high that it wouldn’t leave enough aid for wealthy districts, causing their children start missing out on basic services, or demand so much extra from the state that other essential programs would need to be cut?

An examination of school funding by Indiana’s Legislative Service Agency, the legislature’s research arm, showed the district judged by the formula as most needy — East Chicago, where 96 percent of students are poor enough to qualify for free or reduced-price lunch — received $8,092 per student in 2013.

The district considered least needy by the formula — Northern Indiana’s Boone Township schools in Hebron — received $4,610 per student. The difference between the two was $3,482.

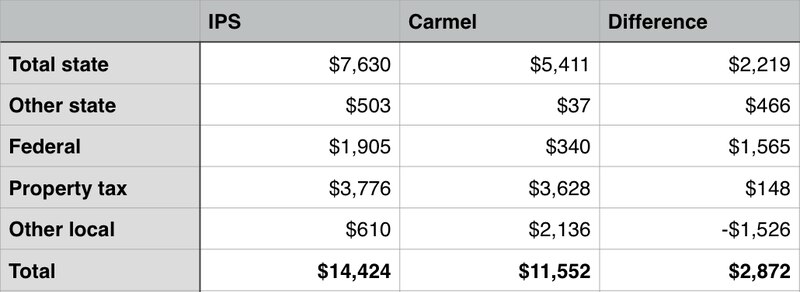

In the Indianapolis area, the formula considered Carmel schools as least needy, awarding it $5,411 per student, while it judged Indianapolis Public Schools most needy, paying $7,630 per student. The difference between Carmel and IPS was $2,219. Carmel’s per student aid was eighth lowest in the state while IPS was fourth highest.

Those funding differences have been shrinking since 2011, when the legislature set in motion a seven-year plan to narrow the gap that lawmakers deemed too wide for per student funding in wealthy communities compared to poor ones.

In effect, the poorest district have been getting a little less each year while the wealthy districts have gotten a little more.

But is the gap too large, as some in the legislature believe, or could it, in fact, be too small?

Different districts with different challenges

Consider the example of Carmel and IPS. When it comes to annual income, Carmel families rank among the very wealthiest in Indiana. Median income in Carmel ranks second only to Zionsville at more than $60,000. IPS ranks fifth from the bottom among 290 school districts with median family income of just more than $20,000.

The difference — about $40,000 a year in extra income per family in Carmel, pays for lots of advantages for many more families in that city.

Among the benefits the extra income can bring are everything from better nutrition and more stable home lives to private tutors, lessons and other learning experiences poorer families often can’t provide.

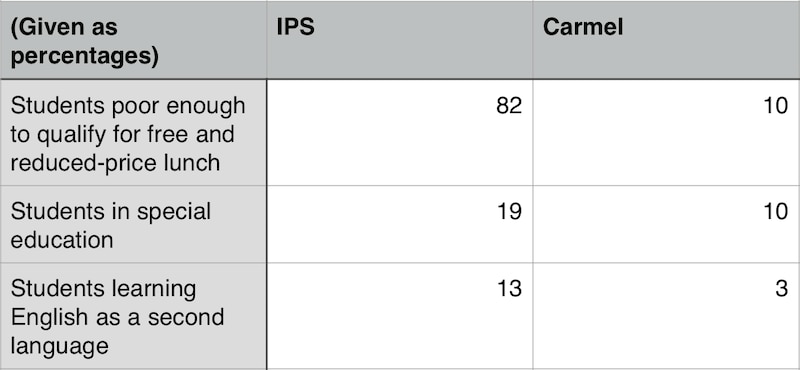

For a sense of the additional challenge, consider the percentage of students who qualified for these extra services school districts must provide in 2015:

Beyond the basic state aid amount, each district receives different types of extra per-student funding. For example, the U.S. Department of Education provides additional money to support students who are poor or are in special education, which benefits IPS especially.

Carmel, by comparison, receives very little federal poverty aid because it has so few poor children. Yet, local taxes passed by referenda contribute significant extra per-student money IPS does not receive.

Some critics of IPS say the extra state and federal aid for poor children should be enough to mitigate its poverty costs. But wealthy districts get extra money from other sources, too, especially if their voters approve extra local taxes. When all these income sources are considered, the total difference in per-student aid between IPS and Carmel in 2015 was $2,871.

But is the total extra amount of just under $2,900 enough for IPS to graduate its students just as prepared for college and work as Carmel?

Providing an ‘adequate’ education

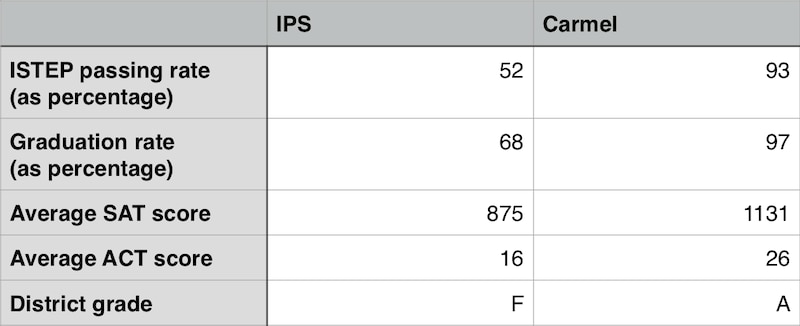

Looking just at the outcomes, the evidence shows IPS fell well short of Carmel in 2015.

Carmel’s children appeared by these measures to be leaving the district among the best prepared students in the state. IPS students, by contrast, ranked among the worst in the state on these indicators.

Many factors play into those results. Some are school-based, some are not. Some might relate to school management problems, or some might suggest more funding is needed.

But would more aid for IPS, instead of the plan for steadily decreasing state aid, make a difference? And how much more would it take to make that difference? Those questions are hotly debated.

Meanwhile, suburban school districts argue that per-student aid amounts below $6,000 — more than a quarter of Indiana school districts were below that number in 2015 — are simply not enough to provide even the basic programs any parent would expect.

Could the state add enough new money to schools to raise per-student funding for wealthy districts without taking money away from poor schools? Or should voters in those communities be expected to raise local taxes on their own to fill those gaps?

More changes in 2015

After another overhaul of the funding formula in 2015, critics were quick to complain that it only exacerbated some of the biggest problems.

They pointed to its effect on the richest and poorest communities. Of the 25 school districts with the highest family income, all of them got more per-student state aid over the two-year budget. But of the 25 with the lowest family income just 12 of them got more money for 2016 and 2017 across the board — in overall state aid and per-student aid. The rest got less in one or both areas.

Republican supporters of the budget plan argued that it helped put all schools on more equal footing. While agreeing that the poorest districts should get more money than the richest, they said those districts had simply been getting too much extra.

-Updated December of 2015