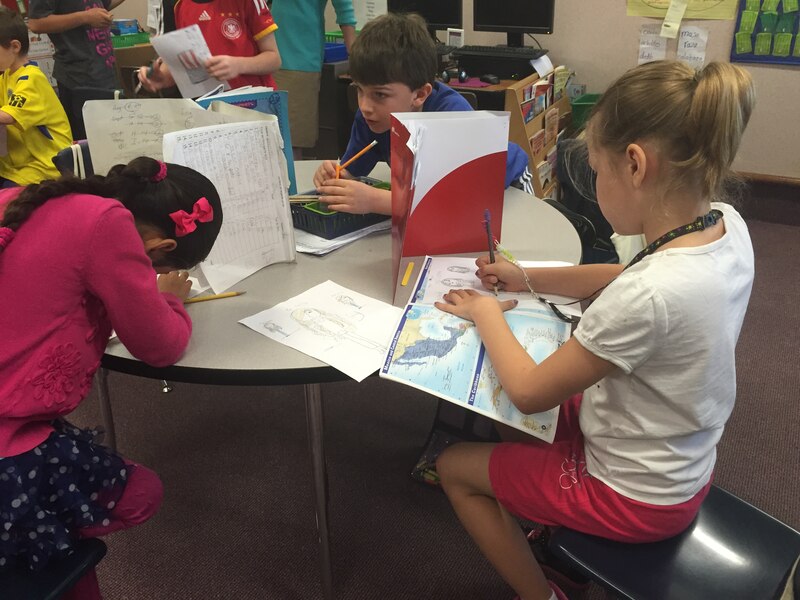

The little boy’s lips were set in a hard line across his face, his head bent over his worksheet as he tightly grasped an orange crayon in his fist while his neighbor chatted freely.

“I already started coloring,” the other boy declared. “Crayons are more faster.”

But the problem wasn’t that the boys were talking, as it might be in other second grade classrooms. The problem was that they were talking in English.

In Mabel Ramos’ language immersion classroom at Forest Glen Elementary School, even socializing must happen in Spanish. That’s what immersion means — completely surrounding students by a new language until they become fluent.

“It’s going to help as they grow up, not only the academic piece but the personal social skills,” Ramos said. “You want them to be really prepared in every single area, not only academic.”

Forest Glen is Lawrence Township’s Spanish language immersion elementary magnet school. It’s an example of exactly the sort of idea touted by legislators this year as a way to expand career opportunities for students.

Senate Bill 267, passed and signed into law by the governor last month, set up a grant program schools and districts can apply for to create their own language immersion pilot programs, in Spanish or other languages, much like what they already have at Forest Glen.

The township is way ahead of the game: it’s been doing this at Forest Glen for 20 years.

Forest Glen’s assistant principal, Jerome Omar Lahlou, believes this is the best way to learn a new language.

“Research shows that bilingualism can truly and successfully be achieved by language immersion, which is the most effective way to teach a second language to students,” Lahlou said.

Grades K-6: building a strong foundation

It’s not like Spanish immersion at Forest Glen is a small speciality magnet for just a handful of students, as magnet programs sometimes are in other districts. The school is huge: more than 650 kids are enrolled.

But there is still a wait-list. Lahlou’s own children took years to get a spot.

The program is popular with both a fast-growing Spanish-speaking population in the township and families that want their kids to graduate high school fluent in Spanish.

Lahlou said immersion schools are especially helpful for Spanish-speaking students because picking up English is easier when they are learning in Spanish at the same time.

“You are coming to school to learn with the language that you are really learning at home,” Lahlou said. “And then as you learn English along the way, then you transfer all that knowledge to English.”

Lahlou said English speakers get better at Spanish from talking with their Spanish-speaking peers.

“The source of the language became not only the teacher, but from the students around them,” Lahlou said.

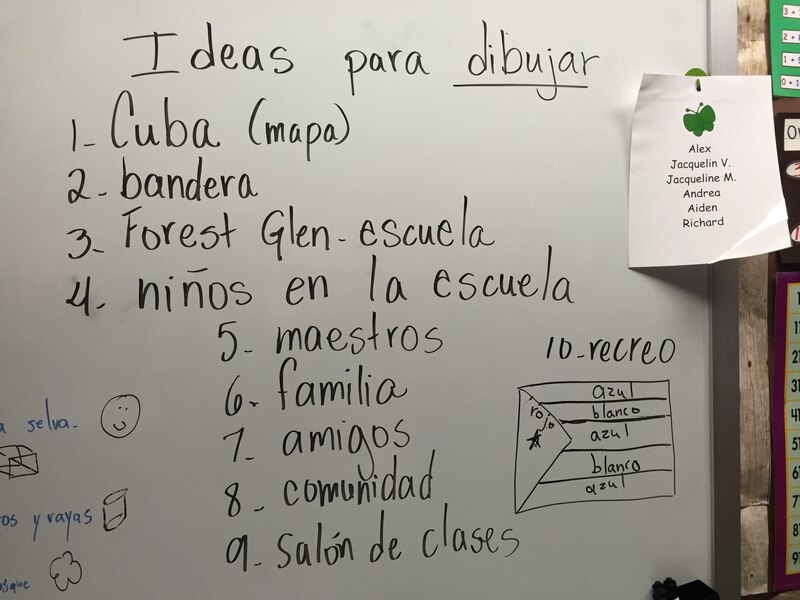

Younger students spend more time speaking exclusively in Spanish. In third grade, that changes to 70 percent. By fourth grade, the day is split 50-50, Spanish and English.

The school has learned over the years that approach works best. Start them with too little Spanish, and by later grades they don’t have a strong foundation in either language. Those splits give kids enough work on English grammar and reading so they can pass ISTEP.

Forest Glen has a 77.6 percent passing rate on ISTEP, higher than both the district and state passing rates. About 44 percent of the school’s students are Hispanic, and 46 percent are from families poor enough to qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, earning an annual income below $43,500 for a family of four.

Lahlou said the opportunity to learn a new language and for Spanish speakers to continue learning in their native language is immeasurable. And he should know — he speaks five: Spanish, English, French, Arabic and Catalan, a Romance language spoken in parts of Spain and France.

“There is really no tool to measure the benefits because there are so many that we don’t even know,” Lahlou said. “You feel like you can achieve things that were not even possible, that you can achieve anything in life.”

Grades 7-8: Moving past social skills

Middle school can be a turning point for immersion students. Either they bolster what they know and approach fluency, or they begin to lose it.

“When they arrive here we can see huge changes in the language,” Fall Creek Valley Middle School language arts teacher Gema Camarasa said. “From seventh grade first day to the end of eighth grade, those two years, if they really work as we tell them to do, day by day, the language speeds up. It’s crazy.”

But sometimes, pride gets in the way, the school’s science immersion teacher, Giselle Andolz-Duron, said.

“Sometimes because of where they’re at in their developmental stage they will resist using the target language, in this case Spanish,” she said. “But when friends come around, all of a sudden they know all the Spanish in the world.”

Middle and high school students have fewer immersion classes than they did in the elementary school program. At Fall Creek Valley, they take science, social studies and language arts in Spanish, as well as an English language arts class and other electives.

Andolz-Duron said it’s the upper grades where students start to gain the “academic language” that allows them to truly discuss subjects like science, social studies, literature and math in another language, rather than just social topics.

But the social connections are at the heart of the program, too. For many students, they’ve been learning with the same kids since Kindergarten. Introducing new kids into the mix in middle school can be difficult because in the beginning, the immersion program primarily served native-English speakers who were being taught primarily in Spanish.

Six years ago that changed at Forest Glen. Fueled by an influx of children who spoke Spanish as their first language, a second approach was used: the dual-language program put both kids who speak English at home and those who spoke Spanish first in class together.

That’s been well-received, but those students are just now approaching middle school age. Current middle and high school students are mostly native-English speakers, with a few native-Spanish speakers joining along the way.

But in two years, the first group of dual-language immersion students will reach seventh grade. Fall Creek Valley Principal Kathy Luessow is excited for how the change will help the school better connect to its increasingly diverse student body.

“I can see where that is going to help us reach more of our families and communicate better with them and invite them to be part of the schooling in ways we have not done before,” Luessow said.

The program as a whole helps open students up to the wider world. They learn from teachers who are bilingual, and many of them grew up in other Spanish-speaking countries. Andolz-Duron is from Puerto Rico, and Camarasa is from Spain. The kids sometimes don’t realize the value of those opportunities, Andolz-Duron said.

“In the U.S., our Spanish speaking population continues to grow and will continue to grow,” she said. “It’s important that we continue to integrate both the language and culture into our mainstream society. It’s everywhere and yet we don’t understand it.”

Grades 9-12: Putting on the finishing touches

By the time immersion students reach Manual Vega’s world cultures class at Lawrence North High School, many are very close to fluency.

“They leave high school really proficient, just some problems with verbs or articles,” Vega said. “They need to polish a little bit more, but they understand everything.”

It was a warm Tuesday afternoon in early May, and Vega had a class of freshmen who he was lecturing about imperialism and colonialism. He lectured some, and the students also read from the textbook.

Rows of students methodically took notes as their classmates read, competently if unenthusiastically, about colonial trade. It was entirely in Spanish, but otherwise it felt like a typical high school class.

Vega, a native Spanish speaker, spoke normally. It was just expected that his students understood. And they did.

Vega has seen the immersion program grow from its infancy. A 32-year teaching veteran from Puerto Rico, 20 of those years have been in immersion classes. Vega started out teaching second grade at Forest Glen in 1995, moved on with his students to fifth grade, and then on to high school. That group of students graduated in 2006.

“I wanted to follow how they are working in the immersion program, improving and seeing that,” Vega said.

Vega helped design the immersion curriculum, especially in the upper grades. In high school, social studies classes are in Spanish, and students can choose Spanish language electives, such as Advanced Placement Spanish Literature or film studies.

By graduation, many native English speakers who have stuck with immersion have no trace of an accent when they speak Spanish. Some go on to study Spanish in college, Vega said, and others even take on other languages, which is a much easier feat when you’ve explored one already.

That decision is still a little far off for Gigi Rowland, a 15-year-old freshman in Vega’s class. She’s not sure yet what she wants to study — maybe medicine, maybe teaching or even business.

But she knows she’ll at least minor in Spanish.

Rowland has been in immersion classes in the district for 10 years, and she knows she’s gotten the chance to be part of something special. The cultural experiences, close relationships she’s built with other immersion students and job opportunities being bilingual will open up to her were worth the years of hard work.

“In a way, I feel bad for everyone else because it’s such a great opportunity, and not enough people are given this,” she said. “It is important to me to take advantage of it.”