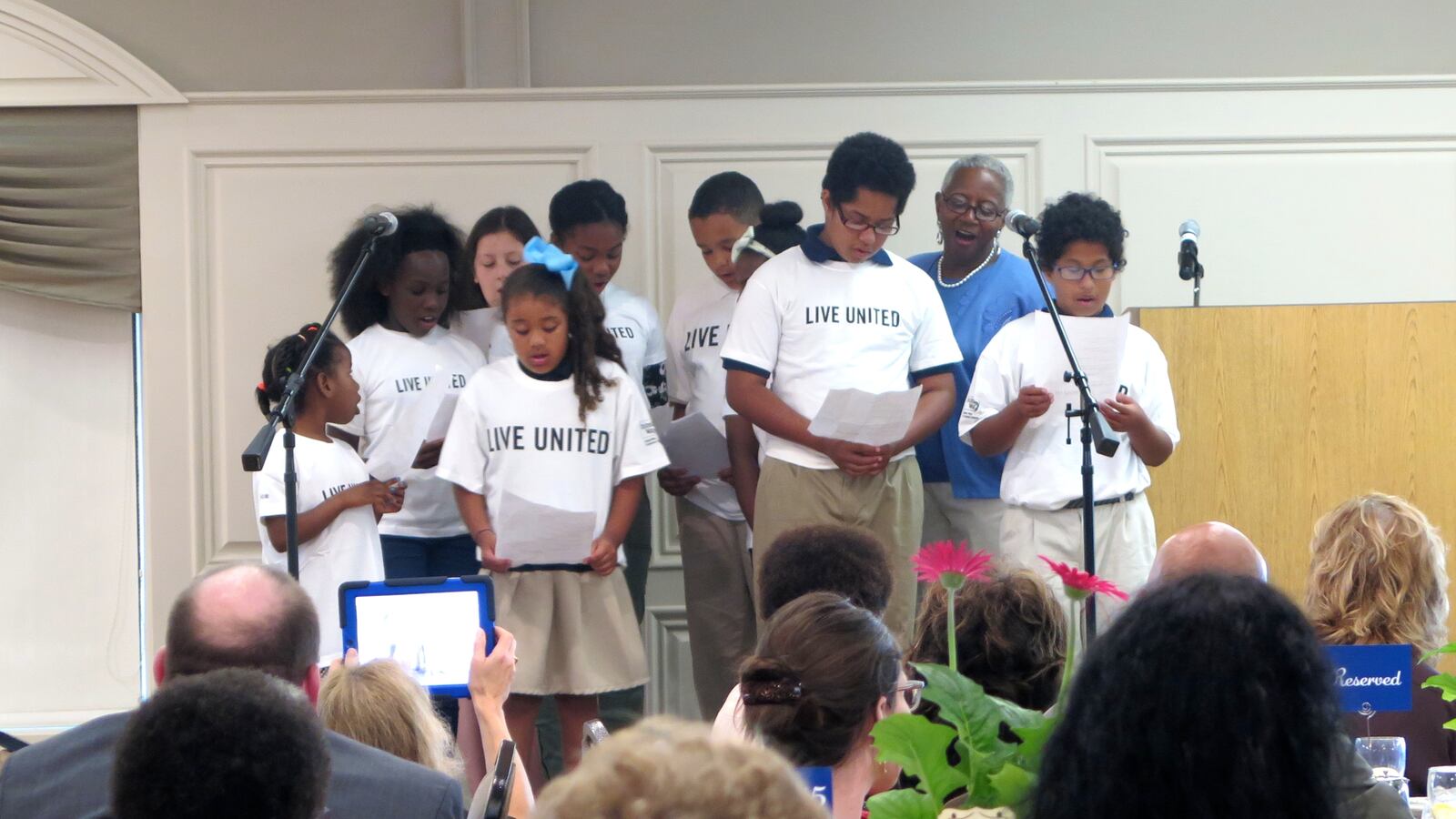

Liz Odle huddled with a group of Indianapolis Public Schools students on Thursday afternoon to sing “thank you for being you” and say goodbye to hundreds of Indianapolis volunteers, businesses and community groups that make up United Way’s Bridges to Success program.

Technically, the 21-year-old program, which this year helped more than 9,000 students in 20 IPS schools with basic needs like tutoring, mentoring, eye exams and other services, is going away next year.

But IPS and United Way say the intention is to expand access to the same services to students in every IPS school.

Odle, the program’s longtime director, is retiring as the program changes hands.

“Every child in every school deserves a chance to succeed,” Odle said. “Our mission was to remove the barriers so that students could be successful. The greatest accomplishment is getting the community to embrace the fact that the education of our kids and the success of our kids does not fall only on that classroom.”

The changes are coming as a result of a recent evaluation of the program, said Jay Geshay, United Way’s senior vice president.

Previously, the program was set up differently in various schools, which he said was difficult to sustain. Twenty schools had “community school coordinators,” employed by IPS, he said, while at other schools the people in those roles worked for community centers.

Now, United Way will help fund two positions to coordinate community engagement work across the district and training for IPS staff that oversees parent involvement. Those IPS workers will now oversee elements of the program at each school.

The new coordinators will work alongside Deb Black, who was hired last year from advocacy group Stand for Children to get more parents involved across the district.

“We recognized that the current models that were in place could not be expanded to all schools,” Geshay said. “In working with IPS leadership, we came up with this new model that allows us to go to all schools.”

United Way’s total investment in IPS is not expected to change, Geshay said. United Way spent $518,000 on Bridges to Success last year, according to the organization.

“The strength of the program has been engaging the community inside of IPS, inside the school and inside the classroom to bring unique assistance to children, whether that is eyeglasses or health testing, tutoring and mentoring, or after school programs,” Geshay said. “All those services and functions will be part of what is going forward.”

IPS Superintendent Lewis Ferebee said the district will continue to work with United Way, and he even hopes to “go deeper” with programs including ReadUP, where volunteers are matched with third- and fourth-graders in IPS schools to help them with reading skills.

About 80 percent of students who had between two and three ReadUP sessions per week passed ISTEP, according to United Way. District wide, just 59 percent of fourth-graders passed ISTEP last year.

“We want to make sure we’re getting the best outcomes from our investments on both sides,” Ferebee said. “Elements of it will still exist. It just may not exist the way it does today.”

Indianapolis’ program, founded by then-United Way of Central Indiana CEO Irv Katz and then-IPS Superintendent Shirl Gilbert, was replicated in at least 12 others cities. It was heralded as one of the leading models of community and school collaborations by Washington, D.C.-based Coalition for Community Schools.

Odle said she hopes services at schools expand, rather than shrink, as a result of the changes.

“It was never the intention just to remain in a few schools,” Odle said. “The reason that we were small and only in a few schools was because that was the best way for us to manage it.”

School 58 Principal Susan Kertes teared up at the farewell event last week as she thought about the impact that the program has had on her students.

Through the program, the Taft, Stettinius & Hollister law firm pledged to spend nearly $600,000 at School 58, which pays for a full-time community and school coordinator, after-school programs and bus rides from those programs.

Without their help, Kertes said her school wouldn’t have been able to afford those programs.

“It made things that were impossible, possible,” Kertes said. “It’s meant opportunity for children and families. My words can’t truly express the gratitude I have.”