By third grade in a Gary elementary school, Arturo Rodriguez had seen just about all of his white classmates vanish.

He wouldn’t have another white friend until he reached college.

And it wasn’t just his classroom emptying out.

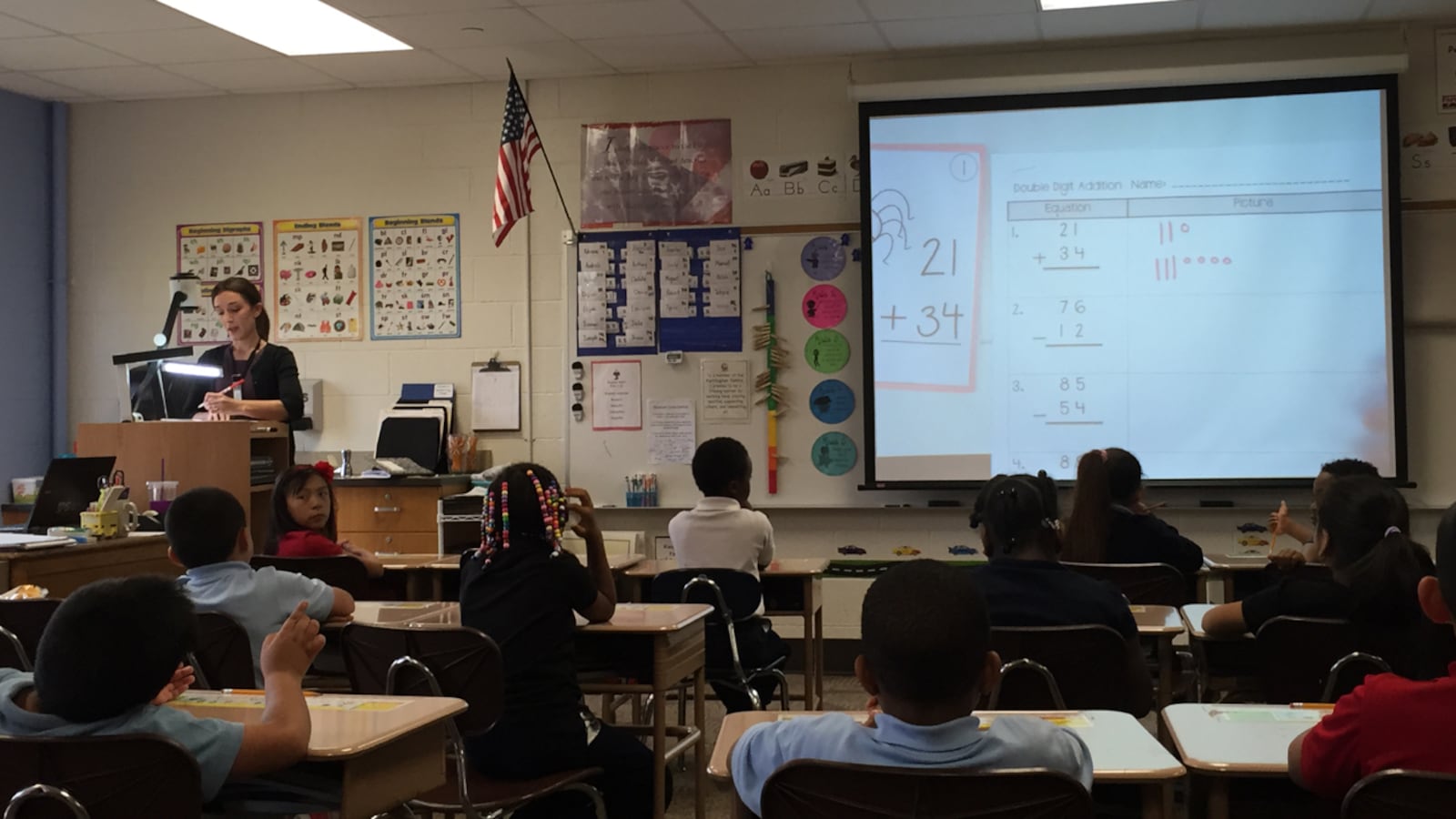

“I saw my community go from a place of business where I can go to the main street and go shopping, to a city that didn’t have a grocery store,” said Rodriquez, 43, now a teacher at Indianapolis Public School 49.

Rodriguez never gave much thought to why those things happened until he had some very frank conversations through a new IPS training program designed to help school staff understand their racial biases. The program, run by the North Carolina-based Racial Equity Institute, breaks down the history and statistics around racism and poverty.

“It helps explain things like why black children are always at the bottom of the academic scale, why black families are always at the bottom when you look at healthcare, when you look at juvenile justice,” said Pat Payne, an IPS educator who has spent 53 years in the district and is leading the push for equity training. “This isn’t just a problem in education, it is systemic and it’s structural, and it runs through everything.”

The Racial Equity Institute has worked with school districts across the country, as well as a variety of state agencies and organizations, pushing people to talk about race and fairness at a time when racial tension makes news almost daily.

As Chalkbeat, the Indianapolis Star and WFYI have reported in an ongoing series about segregation in city schools, IPS faces a steep hill when it comes to racial and economic integration. About 70 percent of IPS students are minority and from low-income families. Indianapolis’ court-ordered desegregation busing program to township schools came to an end this year, leaving schools in the district more segregated than when the program began in the early 1980s.

The Racial Equity Institute trainings, which started in 2014, are one tool the district is using to deal with the effects of segregated schools. School segregation has been shown to leave students of color trailing behind their white peers in test scores and other measures of achievement.

Few in Indianapolis today are considering using busing to integrate schools, but Payne said attitudes about race and school culture are just as important when it comes to educating children of color.

“I do not see our children learning,” Payne said. “I don’t care which form (of busing) you use … because nothing has changed in terms of how people look at black children and children of color.”

In a district where the majority of teachers are white, compared a mostly poor, black and Hispanic student body, talking honestly about racism and poverty is important, Payne said. Research has shown that teachers of all races tend to have lower expectations for what minority students can learn and do in the classroom, which can lead to lower achievement.

The conversations are purposefully direct, addressing the roots of racism and poverty head-on. Although it’s uncomfortable, Payne said, it helps people come to terms with behavior and thoughts they might not even realize have racial overtones.

“Hearing the conversations around ‘What do you like about being white?’ and asking white professionals that question, and asking African-American professionals, ‘What do you like about being black?’ — Just being able to hear the responses was very eye-opening for me,” said Corye Franklin, principal at School 49.

The training also forces teachers to reckon with their curriculum and materials.

“If you have a class that’s primarily Spanish-speaking, then you need to have a classroom library that’s reflective of that,” Franklin said. “We have to make sure that consciousness is there, so that’s what I really try to get (my staff) to understand.”

IPS began the equity training as a pilot with 10 schools, although just nine are currently participating. The goal is to eventually train the entire staff at every school in the district. The sessions are left pretty open — no agenda, no handouts, just talking.

About 40 people meet at a time, along with community members from various local agencies.

Rodriguez said he almost missed his school’s training because he was returning to the United States from his father’s funeral. But as he sat down with a group of more than 30 teachers, administrators and staff for the two-day seminar, he made an important connection.

Rodriguez, who identifies as Latino, had learned at the funeral about a discrepancy between his father’s and uncle’s birth certificates — in the spot for the baby’s race, his father was labeled “black,” while his uncle was labeled “white.”

Suddenly, parts of his childhood made more sense. His uncle and cousins were middle class and lived in a less “rough” part of Gary, he said, but his father, a janitor, couldn’t even apply for a mortgage. Explicit restrictions on neighborhoods where black people could live were legal in the United States until the 1948 Supreme Court decision in Shelley v. Kraemer, but intentional housing segregation continued in Indiana for decades after.

“My uncle had the privileges that white Americans had,” Rodriguez said. “When I was listening to these conversations (at the training), that all started to fall into place. There are so many systems here that we don’t even know about.”

There are three phases for the training, and IPS pilot schools hope to have completed the first phase by the end of the summer. Teacher and principal turnover during the past couple years has made it difficult to move on to the next phases, which include developing plans for change and measuring success, because new staff have to catch up, Payne said.

The entire program could take three to five years to show results, Payne said, but Rodriguez is already noticing a change in his colleagues.

“People were hesitant (to talk about race),” Rodriguez said. “I was ready, but I didn’t want to make them feel uncomfortable. But now, it’s happening, and we can find ways of fixing (racism) and making sure the playing field is equal for all kids.”