One of the best, most sought-after public schools in Indiana is nestled in a failing urban school district.

This school, Center for Inquiry School 84, stands above the tumultuous reputation of Indianapolis Public Schools. It boasts an intensely rigorous curriculum. Experienced teachers. National awards for excellence.

But, even though it’s a magnet school, not all IPS students have an equal shot at this bright spot in urban education. Instead, School 84 is a rare haven of excellence carved out primarily to attract the children of white, wealthy families.

District officials defend School 84 as a critical piece of a plan to keep affluent whites from leaving IPS, a problem faced by urban districts across the United States. They blame society’s self-segregation for creating a school of 331 white students and 22 black students in a district that is 80 percent non-white.

“We can’t change how society organizes itself,” said school board member Sam Odle.

But specific choices by IPS helped create that racial imbalance. When School 84 was launched, the district changed the enrollment policies governing Center for Inquiry magnet schools. Neighborhood kids were given preference. And, at that time, the two existing CFI schools were located in predominantly white or gentrifying areas. That put affluent white populations at an advantage.

What’s more, within the district, only CFI schools offer the prestigious International Baccalaureate program. As a result, the people in some of the district’s most exclusive neighborhoods have special access to its best-performing schools.

“It seems that some folks are being left out, and that is disconcerting and problematic,” said Brian L. Fife, chair of the public policy department at Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne. “That’s disgraceful.”

It contributes to what Fife — and many other civil rights experts — see as a regression of school desegregation since Brown v. Board of Education, the critical 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case that ruled racial separation in schools to be unconstitutional.

“One of the frustrating things about school desegregation is it’s not discussed anymore in the public or in the societal vernacular and discourse. It’s discussed as if it’s already done, and our work is over,” Fife said. “And it’s not.”

Policy change preceded shift in enrollment

Ten years ago, many Meridian-Kessler neighborhood families shunned School 84, which was then a school like any other in IPS.

Wanting a better education for their children, they often chose Washington Township schools or private schools over IPS. They paid for their children to go to the parochial school across the street from School 84, or they paid for their children to attend prestigious schools such as Park Tudor, Orchard and International.

At School 84, located at East 57th Street and Central Avenue, empty desks were filled instead with African-American children bused in from the east side.

IPS revenue was falling as students sought alternatives. To woo Meridian-Kessler families, IPS overhauled School 84 in 2006. The district duplicated an elite and successful magnet program, the Center for Inquiry, which already had attracted a hefty waiting list Downtown at School 2.

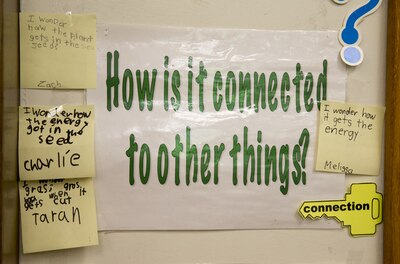

The Center for Inquiry schools allow children to learn by following where their questions lead them. They teach both Spanish and Mandarin, and they are the only elementary and middle schools in IPS to offer the rigor of an International Baccalaureate program, which is widely recognized at the high school level for its advanced courses that can net college credit.

In first grade, students are articulating strategies for solving math problems.

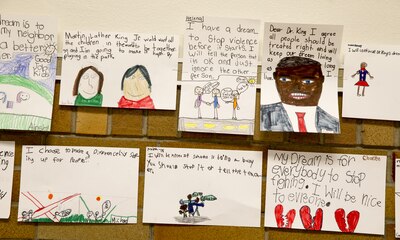

In second grade, they’re writing their own books.

In third grade, they’re learning about different architectural styles of bridges and the physics of how each one holds up.

Unlike other IPS schools, the Center for Inquiry schools don’t suffer from the burnout and turnover of low-paid teachers who work in classrooms filled with at-risk students in chronically struggling schools. The schools hire mostly experienced teachers, School 84 Principal Christine Collier said, who tend to stay at the school for years.

The model had worked so well that the original Center for Inquiry blossomed from one wing of a school into its own Downtown building. It was nestled off Massachusetts Avenue, near posh Chatham Arch and Lockerbie Square neighborhoods, but the magnet school drew students from across the district. Black students, who comprised a little more than half the school, often came from northeast-side neighborhoods. White students, who made up a little more than a third of the school, often came from Irvington. Sixty percent of the school qualified for free or reduced-price meals — still better than the district as a whole.

Magnet schools, a school choice option within traditional public school districts, are supposed to lead naturally to integration by drawing students based on interest and learning style rather than by neighborhood.

But IPS rules have created an opposite effect.

When School 84 opened, the district put into place a new policy: CFI schools would let in students who lived closest — within about a one-mile radius — before opening up available seats to all students through a lottery.

In the 10 years since the rule change, School 2 transformed into a majority-white school. Nearly 70 percent of students are white; just 11 percent are black. In a district where 70 percent of students receive free or reduced-price meals, only one-quarter of School 2’s students qualify for the federal lunch program.

At School 84, the white student population has more than quintupled since it opened. Less than 5 percent of its students are low-income.

For Anne Mills, talking about the lack of diversity at School 84 is an uncomfortable topic because the policy that favored her family is the very reason why her children enrolled in IPS.

“If we wouldn’t have gotten in, we wouldn’t be in IPS,” said Mills, president of School 84’s Parent Teacher Student Association. “We probably would’ve been private, or we would’ve moved. The fact that they’re neighborhood schools — drawing from the neighborhood — is keeping families in that neighborhood.”

The three — soon to be four — Center for Inquiry schools now hold a lofty status within IPS, fast-growing and so high in demand that 300 students were on a waiting list last year. Rumors used to fly over how influential families seemed to leapfrog waiting lists for the schools. Families try to increase their children’s chances of getting in by buying houses within a one-mile radius of the schools. Sometimes so many apply that once the district gives priority to siblings and neighborhood kids, few seats are left for others — and sometimes, even those who live within a mile of the school land on the waiting list.

“If you just plop down a school in a very segregated area with a very stratified class structure, the most privileged kids will be in the most privileged school,” said Gary Orfield, director of The Civil Rights Project at UCLA. “They’re the ones who are going to figure it out.”

Giving preference in other ways

School 84 is the most obvious example of how the district’s policies have catered to affluent white families. But with the program so coveted by those families, and with the rules on their side, the other Center for Inquiry schools also have tracked similar trends.

On the north side, the School 27 is the most diverse of all the CFI schools, because it’s located in a much more diverse neighborhood, next to Martin Luther King Memorial Park.

But even here, IPS gave an upper hand to families from Meridian-Kessler, where median household incomes rank highest in the district. The new school took in students who had been wait-listed from the other Center for Inquiry schools. Once they enrolled, their siblings get first dibs in their class of applicants to go to the same school.

Black students outnumber white students at School 27, but that margin is thinning. While there were once twice as many black students as white students, they are now within 5 percentage points of being even. The proportion of middle-class students has doubled, so that now fewer than half of students receive free or reduced-price meals.

Where you put a school matters. That’s why so many people worried about where the district placed the newest CFI school, opening in the upcoming school year.

School 70 is on the southern edge of Meridian-Kessler. District officials said they picked it for the fourth CFI site to accommodate the neighborhood demand. The school first accepted students off CFI waiting lists and students whose schools were closing — such as Key Learning Community — and then by open lottery across the city.

A map of the Center for Inquiry waiting lists showed that students in neighborhoods across the district are interested in the program. But many who didn’t get in are clustered in Meridian-Kessler.

“To many, it seems IPS’ ‘favored’ programs, or the ones ‘favored’ by whites, are deliberately being moved into the Meridian-Kessler, Broad Ripple and Butler-Tarkington areas,” the late local radio personality Amos Brown wrote in an Indianapolis Recorder column this past fall. “These blatant moves have raised suspicions that IPS is trying to bolster educational programs on the backs of Blacks and Hispanics for the benefit of north-side whites.”

Unlike the other CFI schools, however, Collier said, School 70 didn’t give preference to students based on where they live.

“We expect a pretty balanced population there both economically and racially,” said Collier, a longtime leader in Center for Inquiry schools who will be principal of School 70.

But some, such as school board member Gayle Cosby, say the Center for Inquiry schools aren’t the only ones that cater to affluent white families. She noted that IPS/Butler Laboratory School 60 similarly has evolved into a majority white school, after the once-failing school was overhauled into a magnet program in partnership with Butler University. IPS gives priority to children of Butler University employees, which is likely to favor white, middle-class families.

The demographics of the school flipped. Gone was the School 60 filled with hundreds of black students and so few white students that some years they were recorded in single digits. In its place is a fast-growing academy where middle-class students are on the rise, and 3 out of 5 students are white.

Cosby, who represents the east side, fears the district focuses too much on retaining white students, at the expense of the black children and other students in the district.

“It’s a misplaced focus,” she said. “Our focus needs to be on offering the best educational opportunities we can. Whoever shows up to take advantage of those are who we serve.”

Other forces also contribute to imbalance

It’s hard to say exactly how many students benefit from the district prioritizing neighborhood families — and how many are blocked out from attending the magnet programs they want. IPS declined to provide data on the magnet lottery system, including how many students get priority to attend schools based on where they live, or through other preferences such as having a sibling attend the school.

The district also did not provide data on how many students are assigned based on a random lottery draw, or how many remain on waiting lists for magnet programs.

“Having problems getting this information prompted us to change the way we collect our data” and require annual reports on magnet programs, wrote IPS magnet coordinator Greg Newlin in an email.

The district canceled and did not reschedule an IndyStar interview with Newlin.

Fostering school diversity can get complicated. The way the city has developed, for example, has affected school dynamics. Affluent couples often used to move out of the urban core to start families. But now Downtown, as evidenced by the residential surge, has become a desirable place to live — close to a desirable school — for well-off young families.

IPS Superintendent Lewis Ferebee also suggested that the under-representation of black students at magnet schools such as School 84 could be due to families not being aware of their magnet options. He said he hopes the annual Showcase of Schools and the district’s upcoming move to a common enrollment system will help lay out choices more clearly.

The district has tried to remove some obstacles to make magnet applications a more equitable process, such as eliminating a requirement for families to tour the school before an application is processed and, this year, giving special consideration to students who have applied to magnet programs for several years without getting in.

“The process, I’m very confident, doesn’t weed any students out from access to those opportunities,” Ferebee told IndyStar. “But I also think it’s a call to action for us to continue to think about how we can replicate our best programs in other neighborhoods.”

District acknowledges diversity problem

Education experts, even those focused on equity, say it’s worth attracting affluent white families to urban districts, because they net more funding for the district, win political clout for public schools and add diversity to schools overall.

It makes sense, too, for any child to be able to go to school close to where they live.

But Collier, School 84 principal, knows her school has a problem with diversity. With students coming from mostly white, mostly rich families, they’ll miss out on the well-documented academic and social benefits of learning from different backgrounds.

She said she would support having the school board re-examine its rules if it can make access to the Center for Inquiry schools more equitable.

“The piece that magnets and districts have to be careful of is making sure everybody has an equal opportunity to understand what the choice is and how to access the choice,” Collier said.

Ferebee said the district may consider “rethinking” the preference that benefits better-off families — not eliminating the policy, but possibly shrinking the radius of the neighborhood that receives priority, so that fewer families would get an advantage in school assignments.

He also emphasizes IPS’ lofty, but imperative, goal to make sure great schools exist in every neighborhood, so all students have access to different kinds of high-quality education. That doesn’t necessarily have to be a CFI school, he pointed out, if that doesn’t fit a student’s style of learning. Good schools can come in a variety of forms, whether that’s through a traditional neighborhood school, one of IPS’ new “innovation” schools or a magnet program.

Plus, cultivating diverse schools may actually support the district’s efforts to entice affluent white families, said IPS board president Mary Ann Sullivan — particularly millennials and younger families.

“I think that they literally actively seek that as a quality in their school, that they are attracted to schools that look like the world their children will be working in and living in,” Sullivan said.

Integration won’t happen without a plan

Across the nation, some schools grapple with similar problems of racial imbalance — and are coming up with ways to remedy them.

Boston Latin School, a prestigious public magnet school that admits students based on test scores, recently came under criticism for its disproportionately low numbers of black and Hispanic students, which many say contribute to tense race relations within the school.

And earlier this year, a New York Times headline read: “New York Schools Wonder: How White Is Too White?”

Courts have ruled that race alone cannot be the determining factor in school assignments. But schools could cap how many students they draw from the immediate neighborhood.

To balance magnet schools that middle-class families flock to, and schools in gentrifying neighborhoods, some New York principals set aside a certain proportion of seats for low-income students, English-language learners, students in the child welfare system or students with an incarcerated family member.

Integration has to be purposeful, argues Orfield — which is exactly why the courts ordered the desegregation of schools. Schools should have diversity goals, reach out to underrepresented populations and provide transportation.

There’s no magic number to what a diverse school looks like. Orfield describes it as a healthy mix of two or more demographic groups. A predominantly African-American school in a predominantly African-American district, for example, may not necessarily be considered diverse.

Diversity is supposed to be a key mission of magnet schools. And it can be a particularly “difficult sell” to suburban parents, acknowledged John Laughner, legislative and communications director for Magnet Schools of America.

Districts have experienced backlash when they try to shift school assignment policies in an effort to promote diversity, if families once funneled into a higher-performing school lose their priority status, Laughner said. And many parents may be reluctant to send their children to schools in low-income urban neighborhoods, or racially isolated schools.

Achieving diversity “is a big lift,” Laughner said, “but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be sought after.”

Call Indianapolis Star reporter Stephanie Wang at (317) 444-6184. Follow her on Twitter: @stephaniewang.