It was the first week of school and teacher Andy Slater wanted his new class of ninth-graders to understand the school’s rules.

Students must wear long pants — not shorts — so he tugged at his pant leg and gestured, holding his palm up as if to ask a question.

He made a similar gesture as he pointed to his head, asking students if they thought hats were OK. Then he directed the class to series of photos displayed on a classroom screen to give students an idea of which outfits are acceptable for school.

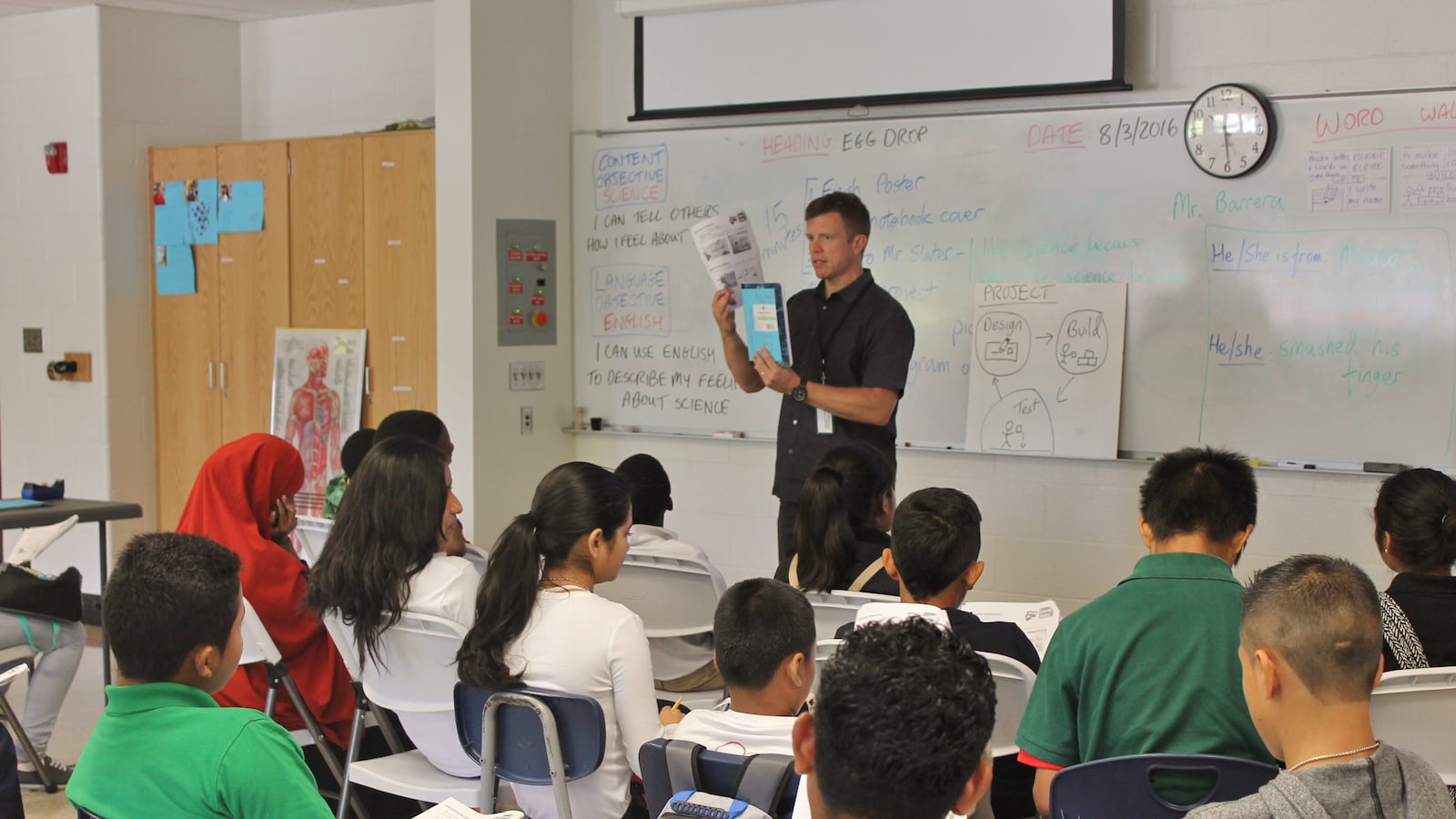

Discussing school rules might seem like simple, standard procedures for the first week of school, but Slater is teaching at a new Indianapolis Public Schools program for students who have recently arrived in the United States, and most of his students are still struggling to learn English.

The Newcomer program enrolls only students who received low scores on an English language proficiency test and the school’s 68 immigrant and refugee students — all in grades 7-9 — come from a mix of countries including Mexico and the Congo. Collectively, they speak 10 different languages.

The language barrier means teachers like Slater have to come up with creative ways to communicate — like giving a slideshow on the dress code.

“The challenge is finding what each kid’s individual strengths are,” Slater said. “I’m presenting myself that I’m learning their languages, too, and that I’m learning their culture.”

So far, it’s working. Slater’s students were engaged in his dress code presentation. They laughed at his photos and shouted ‘No!’ when he showed them a picture of bedroom slippers.

Another educator, Eileen McGinley, a member of the district’s English as a new language team, helped a lost student find his class when he emerged from the wrong room looking confused.

“What grade are you in?” McGinley asked.

“Nine…ninth,” he repeated.

She led him down the hallway to the math classroom where one of the two ninth-grade classes was already settled. He looked into the room and shook his head.

While walking to the next classroom, McGinley asked the boy his name.

“Mbeomo,” he answered.

“I like,” McGinley said, gentling tugging on the sleeve of the boy’s tie-dye shirt.

“Do you know what color this is?” she asked him. “Green — verde — green,” she said, using the Spanish and English words for the color, though Mbeomo is from Tanzania and doesn’t speak Spanish. “Now you say it.”

“Green,” Mbeomo said tentatively. “Green.”

Together, the two tracked down Mbeomo’s correct class: English. He settled in and opened up his notebook, ready to learn some more new words.

The Newcomer program — based on the second floor of IPS’ Gambold building on the northwest side of city — is the first of its kind in Indiana.

Cities like New York that have a long history of welcoming immigrants have had programs like this one for years, but IPS officials decided to add the program after realizing that the number of immigrants moving to the city has grown. The district educated 4,338 kids learning English last year, up from 2,970 students in 2006.

In this inaugural year, the district decided to target the program to adolescents because older kids are especially vulnerable to falling behind or having difficulty picking up a new language. The district plans to expand to grades 3-6 next year and serve up to 160 students.

IPS staffers prepared to open the school by visiting similar programs across the country. But staff did not have much time to get ready because the school board didn’t vote to approve the program until April. That left just four months to prepare the curriculum and recruit and train staff.

As a result, the school is “still working out the kinks,” said Jessica Feeser, who coordinates English as a new language programs for IPS and spearheaded the launch of the Newcomer program.

That means that Feeser must fill in as the school coordinator — a role similar to principal — until the woman hired for that job can start in three weeks. It also means recruiting a social worker and school counselor — two jobs that remain unfilled. And it means ordering enough keys and walkie-talkies so that each staff member has one.

But even as they work out the logistics, the school’s teachers and staff say they have big goals for their students.

“My vision is that we provide an environment where students are safe and feel welcome,” Feeser said. “And that they know their teachers are doing everything in their power to help them learn English.”

For at least one school staffer, that’s a mission with a personal significance. Parent coordinator Mastora Bakhiet came to the United States in 2004 as a refugee from Darfur. She remembers what it was like to move to a new country with a new culture and to send her children to a new school where they barely spoke the language.

“It is a hard thing,” Bakhiet said. “When you come the first time and you don’t have knowledge of the language.”

Parents might struggle with reading food labels or understanding government documents, Bakhiet said. They might have difficulty communicating with their children’s teachers or reading letters the kids bring home from school.

The Newcomer program considers helping parents part of its mission. The program plans to offer services such as adult English classes and health care and mental health services. The school also hopes to partner with community organizations such as the Immigrant Welcome Center, which might set up an office in the school.

“This program is going to be for our children,” Feeser said. “But also for our parents and communities because there is so much to learn about our schools.”