The poster-covered classroom walls at Warren Township’s Hawthorne Elementary School could resemble those anywhere.

But mixed in with the inspirational messages and themed bulletin boards are displays of reading levels, test scores and progress reports. That’s because there’s a clear expectation that students be aware of how much they’re learning at any given time.

This awareness, coupled with a “learn-at-your-own-pace” philosophy, comprise what educators call competency-based or mastery-based learning. Students move through material at their own pace, and once they’ve shown they understand a concept, they can go on to another or explore it more deeply — time spent on a subject is no longer the marker for how much a kid learns.

“In education, the only thing we held sacred was time,” said Ryan Russell, the assistant superintendent in Warren Township.

Now, Indiana lawmakers are looking to schools like Hawthorne as they propose a pilot program in House Bill 1386 that could offer schools across the state grants to bring the model to their own classrooms.

Although the bill passed with support from Republicans and Democrats, some worried that a small pilot program could exclude urban schools, where larger class sizes and more diverse students could provide a better test of whether the model can work large-scale.

“In order for us to make sure this pilot is doing what it should do, it’s imperative we look at some of the variables,” said Rep. Vernon Smith, a Democrat from Gary. “When you look at the research on competency-based education you find that it has some gaps in it with students of a lower socioeconomic status.”

Across the country, competency-based learning has gained traction. According to a 2013 report from KnowledgeWorks, a national organization that advocates for personalized learning, at least 40 states are exploring competency-based learning.

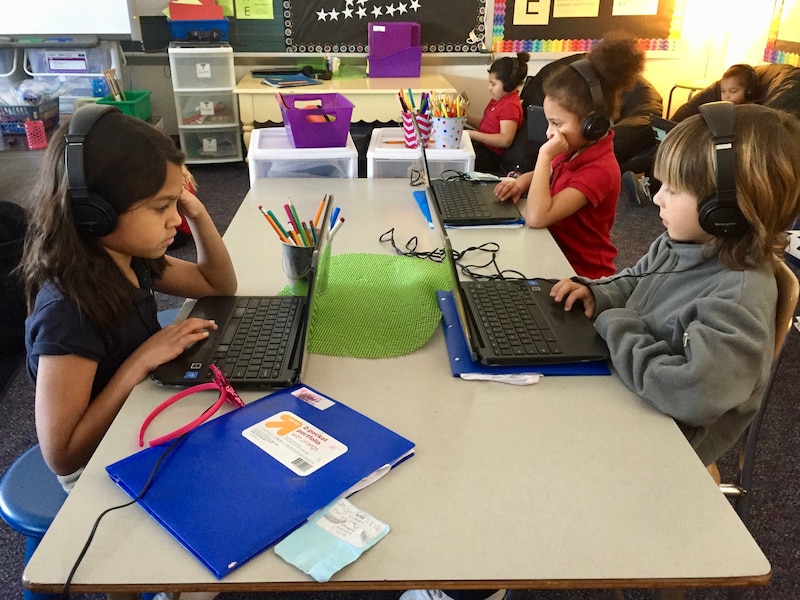

And it’s not playing out in the same way everywhere. Some schools have gone as far as getting rid of grade levels. For Hawthorne so far, it means students regularly use devices like tablets or laptops, teachers and students carefully track test data and students can work in different stations on different subjects. It’s less about getting students to progress quickly and more about allowing them opportunities to dive deeper into the subjects they’re studying, Russell said.

Rep. Bob Behning, the bill’s author, said it won’t attempt to micromanage schools — they would be able to have some support from the state, but they’d figure out the specifics on their own.

“As you look at education and technology and what we have available today, we have the ability to do a lot more in terms of personalized learning,” Behning, R-Indianapolis, said. “Our teachers are doing a great job of that in the classroom already, but this kind of takes it to the next step.”

The bill passed the House 68-21 earlier this month and next heads to the Senate Education Committee.

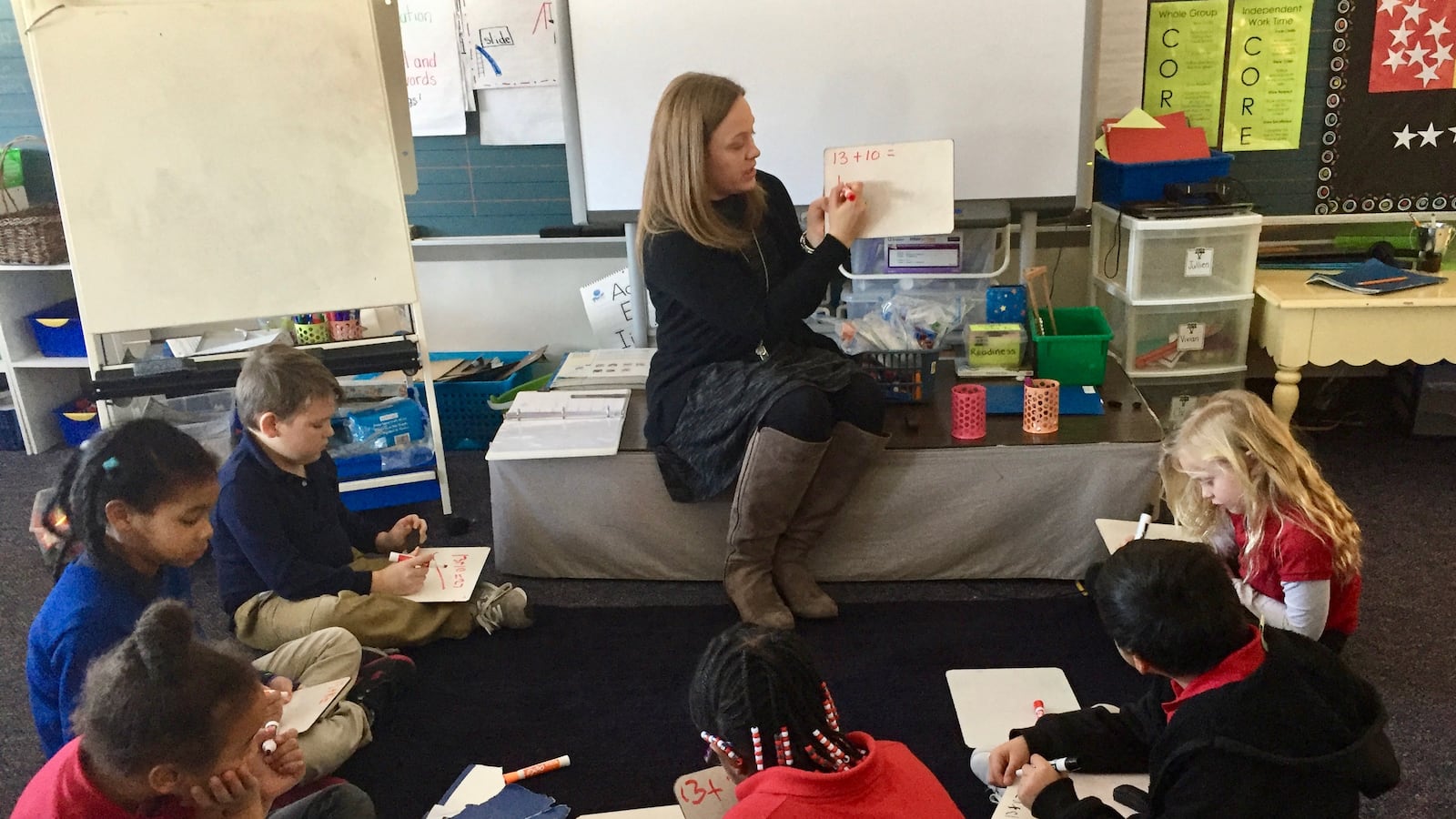

In Amanda Henry’s first-grade math class one February afternoon, students were scattered across the room.

Some sat in a small group with Henry, reviewing simple addition problems on small dry-erase boards. A few feet away, three students sat at a table with laptops working on other math concepts. And in another corner, kids completed worksheets with a partner.

Every so often, Henry addressed the entire room, letting them know how much time they had left for their current activity and directing them where to rotate next.

In some ways, it was a far cry from classrooms today’s parents, and even older siblings, might remember. Desks were not always arranged facing the front, and a lesson didn’t consist of one teacher lecturing a big group.

But to get to that point, teachers need support, too. Russell said that was a big part of how the district approached moving to competency-based education, and he also thinks it’s a key component missing from the House bill. When she testified to the House Education Committee, Warren Township Superintendent Dena Cushenberry said personalization can’t stop with the students.

“As we started rolling this out, what we found is everyone deserves a personalized experience, not only our students, but our teachers,” Cushenberry said. “Our teachers are at different levels … we challenged the district staff to look at what every person needs.”

After winning a $28.5 million federal grant that paid for, among other things, research into competency-based learning, Warren Township began to convert its schools.

First and foremost, parents needed to be brought onboard.

The district made an effort to hold informational nights at each school. Parents got to use computers, work in small groups with teachers and see how children might be spread across the room doing different work at different times. The district also presented at every school board meeting and held community forums.

“We didn’t want phone calls saying, ‘Well, you’re not teaching my kids any more,’ even though the very reason we were doing that was so we could better teach them,” Russell said. “This is a paradigm change. It isn’t just a new instructional strategy, in our opinion. We’re really trying to challenge the notion that kids can’t have more ownership over what they’re learning.”

But that doesn’t always mean technology is king, Russell said. One of the biggest misconceptions about personalized or competency-based learning is that it is as simple as sitting a kid in front of a computer.

“Some kids thrive on virtual,” Russell said. “For others, they will do nothing all semester long if they were on virtual. So what I think we’ve learned most is we have to know more about our students to make sure we are helping guide them in the right direction.”

Going forward the district is still trying to get all the schools phased in over the next few years and work on any kinks. For example, in high school, there are still some restrictions to qualify for NCAA sports in college — and the athletic conference doesn’t accept some virtual classes. But Russell emphasized that competency-based learning is about more than virtual education, which is just one aspect of student learning.

It’s still early for Warren to measure the effect on student achievement. The district has surveyed teachers and students at its other schools using competency-based learning, and have found so far that most teachers say they enjoy their jobs more. Students have reported that they feel their teachers know them better.

Looking at test score data, the Northwest Evaluation Association’s MAP test is the best indicator school officials have to see how kids are learning, Russell said. Schools that have had the competency-based model for a full year met more learning goals, and overall, all schools with the model are seeing more MAP test improvement among students.

But although Russell says there’s plenty of work still to be done, he’s happy with the district’s progress. While he acknowledges this is a big change, there’s also plenty that won’t change, he said. Teachers will still work with students as they always have, and computers won’t replace those kinds of interactions. Grade levels probably aren’t going anywhere, either.

“We’re not ready to get rid of grade levels, and I don’t know that we ever will be,” Russell said. “Our intent was always that every kid who walks into every classroom gets more of what they need and less of what they don’t.”