Communities across the U.S. are breaking away from larger urban districts, exacerbating segregation by race and class and draining money from school systems with the highest needs, according to a new report.

“This isn’t a story of one or two communities,” said Rebecca Sibilia, CEO of Edbuild, which released the report Wednesday. “This is about a broken system of laws that fail to protect the most vulnerable students.”

So far, the phenomenon of school district “secession” has largely bypassed Indianapolis, in part because the city’s schools are already separate — 10 districts surround Indianapolis Public Schools. That’s by design: State lawmakers wanted to avoid local backlash, so they chose not to merge school districts when Indianapolis and Marion County unified in 1970 under “Unigov.”

The national report from EdBuild, a nonprofit research group focusing on education funding and inequality, highlights districts across the country that have had some of the most dramatic secessions. A particularly egregious example is when six suburban towns within Shelby County split off from the Memphis school system. In Tennessee, municipalities with at least 1,500 students can secede if a majority of local voters approve.

Unlike Tennessee and other states where secession is common, Indiana law is less friendly to breakaway districts. If a community wants to split from a larger district, they must have the backing of a county committee, the Indiana State Board of Education and 55 percent of local voters, the report said. During that process, state and county officials have to consider how that move would affect school finances.

Since 2000, just one attempt at district secession has occurred within the state. The East Madison school district tried to secede from Anderson Community Schools in 2012, but the move was defeated.

There have not been any efforts for school districts to secede in Marion County, where they are already highly fragmented. In fact, the decision not to unify schools when the city and county merged has had far reaching effects.

As Chalkbeat reported in a story last year, the courts would later call that decision discriminatory, and it was a primary argument a federal judge cited in 1971 when he ordered desegregation busing of IPS students across school district lines into the townships. The program began in 1981 and ended last June.

The judge who ordered the busing, Samuel Dillin, stated bluntly that a merged city that left 11 separate school districts was racially motivated at a time when a majority of the region’s African-American and minority students lived in the city center while the surrounding school districts primarily enrolled white students. “Unigov was not a perfect consolidation,” then-Mayor Richard Lugar told Chalkbeat. He went on to be one of Indiana’s most legendary political leaders as a six-term U.S. senator. “A good number of people really wanted to keep at least their particular school segregated.”

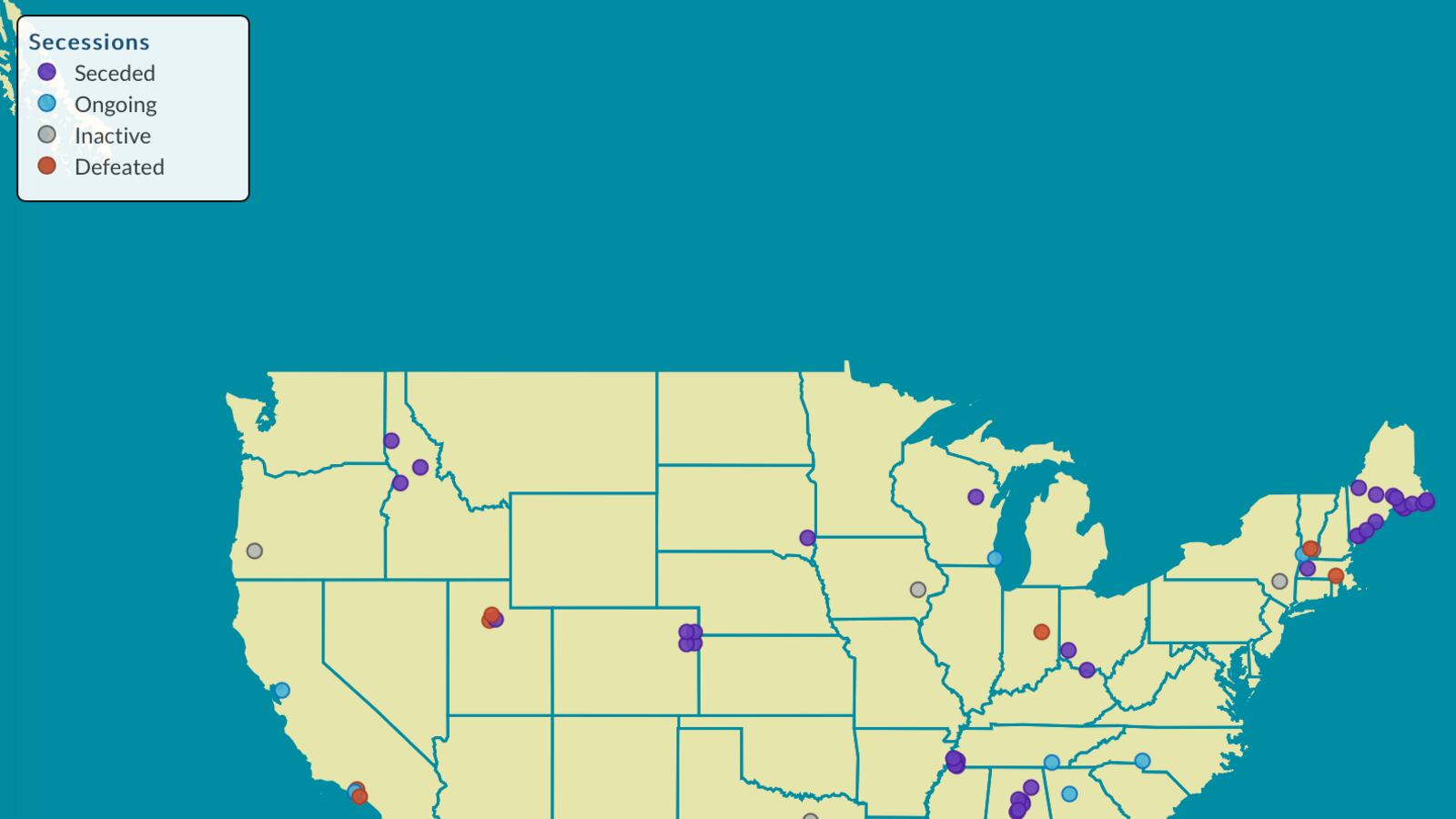

You can find EdBuild’s interactive graphic here and the entire report here.