New rules designed to make Indianapolis Public Schools’ most sought after schools more accessible for low-income families and children of color appear to be working. But with admissions still skewed, the administration is proposing going even further.

Across IPS, just one in five students are white and nearly 70 percent of students are poor enough to qualify for meal assistance. But at three of the district’s most sought after magnet schools, white students fill most of the seats and the vast majority of students come from middle class or affluent families.

At a board meeting last month, district staff highlighted School 60 (the Butler University lab school), School 84 and School 2 (both Center for Inquiry schools) as three schools where seats fill up fast and enrollment doesn’t reflect the demographics of the district.

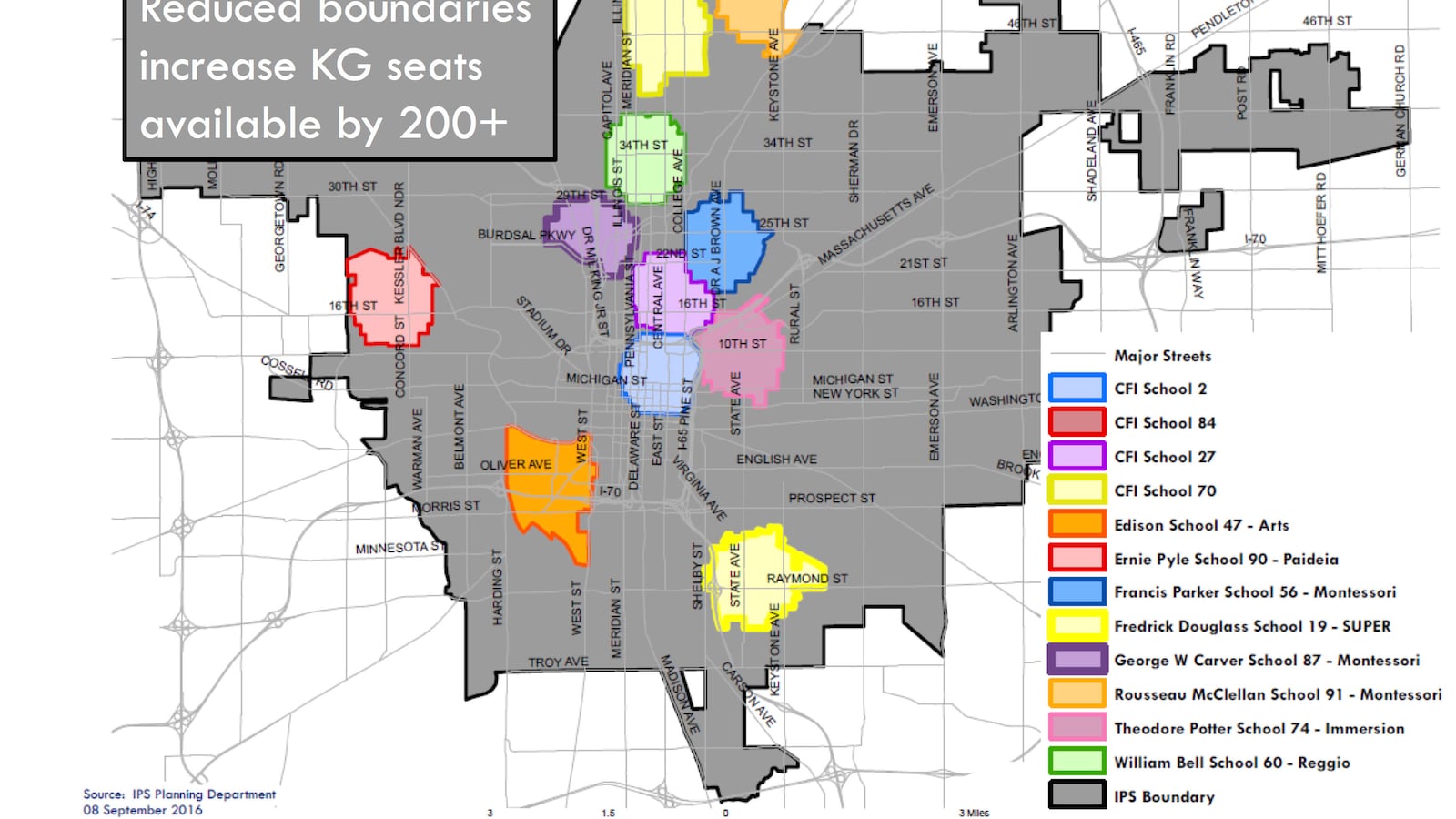

In a bid to make those schools more accessible for low-income families and children of color, the board changed the admissions rules for magnets last fall. They shrank the boundaries that give priority to families who live near the schools, which is important because the three most popular schools drew from areas with more white, affluent families. And they changed the timeline for magnet admission to allow families to apply later.

“Magnet schools were born out of the civil rights movement and were intended to help school districts to re-integrate,” former-board member Gayle Cosby said at the time. “We want to make sure that magnet schools are not actually serving a different purpose in our district.”

The changes appear to have opened Schools 2, 84 and 60 to more students of color, according to data from the first admission cycle under the new rules. Next year, 32 percent of kindergarteners are expected to be children of color. That’s more than double last year, when just 14 percent of kindergarteners were not white.

But those demographics don’t come close to matching the district, where 72 percent of kindergarteners are children of color.

IPS director of enrollment and options Patrick Herrel said the goal should be for admissions at the most popular magnet schools to reflect district demographics.

“All kids, regardless of background, (should) have an equal chance of accessing some of our highest quality schools,” he said. “We moved in the right direction, but we are absolutely not there yet.”

The changes also aim to make the schools more economically diverse, but the data on income diversity among kindergarteners won’t be available until students complete enrollment and income verification paperwork, according to an IPS official.

District staff say IPS could do more. Last month, they presented the board with a plan to reserve more seats for students who apply late in the cycle. IPS data shows that students who apply later in the spring are more likely to come from low-income families and to be children of color.

The move would double down on a change made last year, when the district switched from a single admissions lottery in January to three lotteries. Last year, 70 percent of seats were available in the January lottery, but 30 percent were held for lotteries in March and April. The new proposal calls for going further by reserving half the seats at magnet schools for the March and April lotteries.

When the board voted on the change to admissions rules last fall, there was strong momentum behind the move to change magnet lottery rules, following a Chalkbeat and IndyStar series on segregation in schools that found the district’s most popular programs primarily served privileged students. But there was also resistance from some parents, many of whom came from neighborhoods that lost their edge in gaining entry to popular schools.

It’s unclear whether board members will be willing to risk more backlash from parents who have the means to travel to other districts or pay private school tuition. The board did not vote on the latest lottery proposal, and it received mixed feedback.

Board member Diane Arnold said she supports holding more seats for later lotteries when more children of color apply.

“I like the fact that we are looking at playing with those percentages … connecting that to equity and trying to get more children engaged in those programs,” she said.

But board member Kelly Bentley was more skeptical. Equity is important, she said, but if parents don’t know whether their children are admitted to their top choice school until late April, they might choose another school.

“That’s a … loss of a student and a loss of revenue to the district,” she said. “I think we need to be very careful on making any changes.”