Ebene Burney has always had a side hustle during her seven-year teaching career. She used to help her husband with his business. Now, she spends Saturday nights overseeing teens at the YMCA.

“It’s not that much extra, but it does help pay a bill,” said Burney, who moved from Fort Wayne about a year and half ago and says she loves her job teaching in Indianapolis Public Schools.

If teachers were paid better, she thinks fewer educators would leave the classroom. “Teachers have families,” she said. “Teachers are just regular people that need to make a living.”

Teacher and principal salaries, benefits, and raises are at the center of a rocky monthslong campaign to convince voters to raise their own property taxes to increase Indianapolis Public Schools funding. An operating referendum calls for about $220 million over the next eight years and will be paired with a second tax measure that would raise $52 million for building improvements.

Increasing teacher pay could come with a substantial price tag — salaries are the district’s largest expense. (Last year, about $158 million of the $400 million budget went to salaries.) But advocates say it is a matter of fairness because teaching is a challenging job where pay is lower than in fields that require comparable education. District leaders also argue that paying teachers more would offer benefits for students, by increasing the quality of teachers and lowering teacher turnover.

Educator salaries could be a good way to sell the referendum to voters since, nationally, teacher pay is a hot topic. In states like West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Kentucky, teachers have walked out in protest of low pay and school funding. Stories about teachers like Burney taking on second jobs frequently circuluate, including a recent one about teachers who make extra money as “influencers” on Instagram. A recent poll from Ipsos/USA Today found that 59 percent of Americans do not believe teachers are paid fairly.

Indiana has not had as much political upheaval around salaries as some states have, but there is still simmering discontent over shifts in state funding that have hit some high-poverty districts especially hard, recession-era pay freezes, and salaries that advocates say are too low.

For Indianapolis Public Schools to offer teachers raises of any amount, district leaders argue that local taxpayers must foot the bill. We have the details on the plan and how it would shake out for students and teachers in Indianapolis.

Raises for teachers could be small. But supporters say even small raises matter.

Even if the referendum passes, the raises in store for educators could be relatively low.

Ferebee has only committed to “inflationary” raises of 2 percent per year for teachers if the referendum passes. “We hope that we can clearly do more than that,” Ferebee said. But, he added, “that has to be bargained” with the teachers union.

In part, the proposed raise is relatively small because the money the district raises won’t just go to pay increases. It will also pay for existing salaries and for health benefits, which are increasingly costly, said Ferebee.

For the district to afford substantial pay raises, it would need either a big boost in funding or to make aggressive cuts to the rest of its budget. With little say over how much money the Republican legislature allocates, district officials are planning to focus on aggressive budget cuts, which could include closing schools and reducing the number of teachers. Those cuts are at the core of an unusual agreement between the district and the Indy Chamber, which is funding an effort to shrink Indianapolis Public Schools spending over the next three years.

The district teachers union will bargain for a larger raise, said Rhondalyn Cornett, the president of the Indianapolis Education Association. But even if the raises teachers receive are only 2 percent, that’s significantly better than facing pay freezes or cuts, she said.

Teachers in nearby districts are often paid more.

As one of 11 school districts in the city, Indianapolis Public Schools is in an unusually difficult position when it comes to attracting educators. Teachers with in-demand expertise in fields such as special education or science can readily move to neighboring districts, many of which offer higher pay.

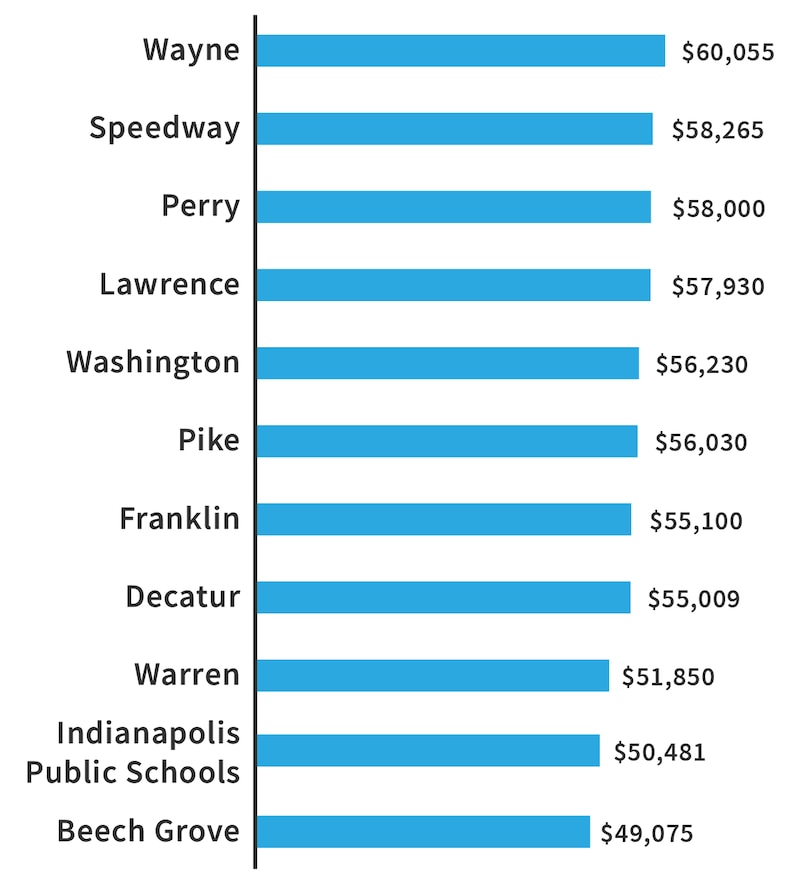

New teachers in Indianapolis Public Schools typically make about $40,000 per year while the average teacher in the district makes about $50,500, according to state date from 2016-17. There are other Indianapolis districts with comparable starting pay, but only one — Beech Grove — pays new teachers less.

The divide continues as teachers move up the ladder. When experienced educators reach the top of the pay scale, their salaries max out at about $72,700 in Indianapolis Public Schools, thousands of dollars below other districts.

Average teacher pay in Marion County 2016-17

Sherry Smith has been teaching for more than 20 years, and she was planning to retire about four years ago. She even turned in her retirement from her job in Warren Township. When she and her husband took custody of their grandchildren, however, she realized she needed to keep working. That’s how she ended up taking a job as a special education teacher in Indianapolis Public Schools.

The move from Warren to Indianapolis Public Schools, however, came at a cost: Smith took a pay cut of more than 10 percent, she said.

Teacher pay in Indianapolis Public Schools has been a source of strife for a long time. Beginning during the recession, teachers in the district faced years of pay freezes. In 2015, the Ferebee administration negotiated a contract that bumped up the base salary, and teachers have continued to move up the ladder. But because recent raises have not made up for the freeze, pay still lags for many teachers who remained with the district throughout, said Cornett.

Those raises cost the district about $4.35 million in 2015-16 and $6.52 million in 2016-17, according to the administration, plus additional payroll taxes and retirement contributions.

Teacher pay doesn’t just affect teachers. It also affects students.

The gap between teacher pay in Indianapolis Public Schools and other nearby districts is not only a problem for teachers. It also may be bad for Indianapolis Public Schools. Each year, about a quarter of the district’s teachers leave, according to a chamber analysis confirmed by the district.

Ferebee and Cornett both agree that one of the most straightforward ways of improving teacher retention and recruiting new teachers is by increasing pay.

“If you’re going to retain the people that you have, the talent that you have — and we do have some talented teachers — and we want to recruit more talented teachers, I’m sorry but money is a big part of it,” Cornett said. “It’s still a relevant subject.”

That’s backed up by research in other places. As Chalkbeat has reported, several studies have shown that even small increases in teacher pay and bonuses decrease the number of teachers who quit, and they can attract more effective teachers.

Ultimately, reducing teacher turnover and increasing teacher quality could have benefits for students. A Texas study, for example, found that increased teacher pay not only boosted retention but also likely led students to do slightly better on tests as a result.