Indiana Virtual Pathways Academy is one of the state’s largest and fastest-growing schools. But because too few of its students took the state exams — and those who did weren’t enrolled long enough — there is no clear picture of how well the school is educating them.

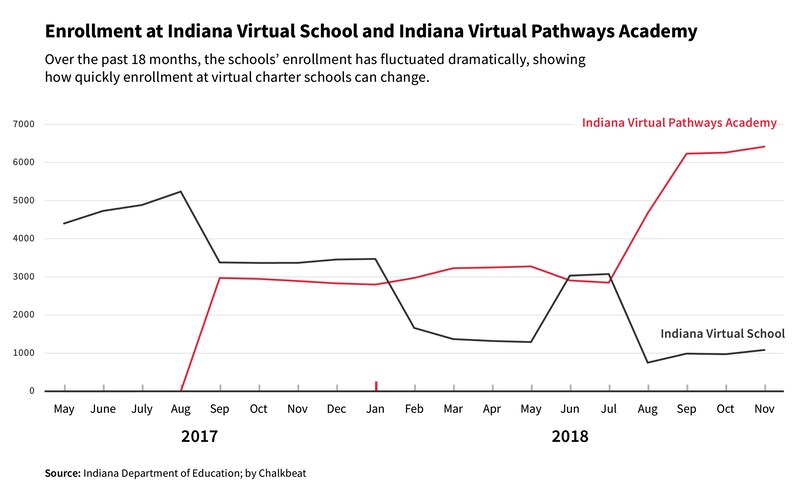

The virtual charter school, which opened in 2017, more than doubled in size to 6,232 students since last fall, in part because state data shows thousands of students have transferred from its troubled sister school, Indiana Virtual School. In 2017, almost 3,000 students from Indiana Virtual School transferred to IVPA, and in 2018, more than 1,700 students did.

But despite Indiana Virtual Pathways Academy’s rapid growth, the school is bypassing a key accountability measure that Indiana thinks is important for transparency: A-F grades, which were approved by the Indiana State Board of Education on Wednesday.

Education department officials said the school did not get a grade, despite its high enrollment last year, because it did not test enough students who had been enrolled long enough to have one calculated. State grades are based primarily on student test scores, and virtual schools are known to struggle to get their remote students to sit for exams.

State test participation rate data shows IVPA tested about 19 percent of its 346 10th-graders in 2018 — about 65 students. To use test scores to calculate a school grade, the state requires that at least 40 test-takers must have attended the school for at least 162 days, a majority of the school year. But state officials said that while the school enrolled 48 10th-graders who met the attendance threshold during the testing period, only three of those students took the exams.

Federal requirements say schools must test at least 95 percent of students, and school grades can be affected if a school falls below that percentage. But there is currently no consequence for a school that doesn’t test enough students to get a letter grade.

The students who were tested at IVPA posted poor results: 5.7 percent passed both state English and math exams.

Leaders from Indiana Virtual School and IVPA did not respond to requests for comment on A-F grades or testing participation, but the schools’ superintendent Percy Clark said in an emailed statement that students from varying education backgrounds select IVPA, and that the school was designed to serve students who are far behind their peers academically.

“Our students CHOOSE to come to Indiana Virtual Pathways Academy from many different backgrounds, and we accept everyone regardless of where they are on their academic journey,” Clark said.

Virtual charter school critics say IVPA’s lack of a letter grade is an example of how the schools are able to avoid scrutiny.

“It’s absolutely indefensible,” said Brandon Brown, CEO of The Mind Trust, an organization that advocates for charter schools but has been a vocal critic of virtual charter schools. “When it comes to charter schools, the grand bargain is that the charter school gets increased autonomy, and in exchange, there is greater accountability. It’s hard to see where the accountability is for virtual schools right now.”

In contrast to IVPA, other large virtual schools in the state tested at least 90 percent of their students, and nearly every traditional school in Indiana met the federal threshold for testing students.

Indiana Virtual School, the subject of a Chalkbeat investigation that revealed questionable educational and spending practices, tested about two-thirds of its students in 2018. Students at the school, which received its third F grade from the state this week, did marginally better than at IVPA, but performed far below state averages: 18.6 percent of elementary and middle school students passed both tests, and 4.4 percent of high-schoolers did. State law says schools are up for state board of education intervention when they reach four consecutive F grades.

Brown, who used to work in the Indianapolis mayor’s office overseeing charter schools, said this is where charter school authorizers — the entities charged with monitoring the schools’ operations, finances, and academics — need to be involved. Daleville Public Schools, a small rural district near Muncie, oversees IVS and IVPA. State education leaders have previously questioned whether school districts have the capacity and expertise to oversee statewide charter schools. District leaders did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

“If I was still an authorizer and one of our schools had less than a 20 percent rate of their students taking the ISTEP, we would be mortified, and we would be holding that school accountable with very clear measures,” Brown said. “In light of the tens of millions of dollars used to fund this school, there has to be at least a basic level of accountability, and right now, it’s hard to account for how that money is being spent because we just don’t know.”

With such high enrollment numbers, Indiana Virtual School and Indiana Virtual Pathways Academy could together bring in upward of $35 million from the state for this school year, according to funding estimates from the Legislative Services Agency.

At the state’s other full-time virtual charter schools — including those billed as alternative schools like IVPA — state grades are rising as enrollment grows. Indiana Connections Academy is up to a D this year from an F, and Insight School of Indiana is up to a C from an F. For grades under Indiana’s federal plan, the schools received an F and D, respectively.

Indiana Connections Career Academy enrolled about 70 students last year and received no grade, but education department officials say that is because it had too few students to calculate one, despite testing more than 95 percent of them. It’s not uncommon for small schools — especially high schools that have just one tested grade — to not get a grade. This year, the school’s enrollment is up to about 300 students.

Virtual charter school accountability has become a hot issue in Indiana. Earlier this year, the state board of education convened a committee to study virtual charter schools, which have grown rapidly here in recent years. And last month, the committee released a series of recommendations, including slowing growth of new virtual charter schools to 15 percent per year — after a school hits 250 students — for their first four years.

Getting students who are located remotely to sit for state exams is a challenge for virtual schools. Melissa Brown, head of Indiana Connections Academy, said dogged work contacting and keeping up with students has made some of the difference for her school, both in students taking tests and improving on them.

“Our teachers are relentless in trying to engage with kids,” she said. “We are by no means where we want to be. We still have a lot of work to do. But 8-point growth is something that we’re celebrating today.”

Melissa Brown said the school is also offering students who come in behind grade level more ways to make up their classes and incentives for them to stay at the school. For example, she said the school has a lot of over-age eighth-graders who should be in high school. Instead of just drilling their eighth-grade classes, they also have a chance to try out high school-level work — a taste of what’s to come, Brown said. So far, it’s working.

“We’re just trying to be really creative about helping kids progress,” she said.

At Insight, school director Elizabeth Lamey said she’s excited by how the high school has been able to help students show more growth on state tests. Currently, the school, which opened in 2016, is getting grades calculated only on how much students improve on state tests from one year to the next, not their proficiency or other measures such as graduation rate.

Lamey said improving the school’s curriculum and focusing on remediation and teacher training contributed to their progress and sets them up to continue that work.

“We hope to see even more growth this year,” Lamey said. “We know that it’s a rougher road, the older students get, to remediate. It takes more time, and we are slow and steady — we keep moving forward.”

Accountability issues will continue to be important for virtual charter schools as their enrollments grow.

Indiana’s five full-time virtual charter schools enroll about 13,000 students. Although it appears that total virtual charter school enrollment in Indiana has declined since 2017-18, those figures include the closing of low-performing Hoosier Virtual Academy. The school enrolled 1,170 students when it closed in June, which was far lower than the 3,342 it was recorded as having at the beginning of that school year.

Comparing enrollment totals between fall of 2017 and fall of 2018, every virtual charter school currently open in the state saw enrollment rise, with the exception of Indiana Virtual School. Indiana Connections Academy and its sister school, Indiana Connections Career Academy, gained nearly 400 students between them. Insight is also up 45 students.

Virtual charter schools tend to have volatile enrollment patterns in part because of how easily students can enroll and withdraw — their families don’t have to move, and they can live anywhere in the state. Students moving between schools is not unique to virtual schools, but those schools do tend to see higher instances of mobility than traditional schools.

That means it can be hard to determine just how much virtual school enrollment has changed from one year to the next — enrollment numbers reported in the fall might fluctuate wildly through the rest of year.