The upside of summer, for many students: No homework.

The downside: Losing a lot of what they learned during the school year.

A central Indiana summer program is trying to reverse this widespread backsliding, which research has shown can be equivalent to two to three months of lost reading ability.

Trinity Sanders, 14, is one of 150 Indianapolis students spending six weeks this summer at Horizons, an academic camp program for students from low-income families, whose summer learning loss can be steeper than that of their more affluent peers.

“It keeps me motivated to want to go to school because I’m ahead of everybody since I’m just not at home during the summertime,” Trinity, now in her ninth and final year at Horizons, told Chalkbeat.

Horizons at St. Richard’s Episcopal School is the local arm of a larger tuition-free program serving rising kindergartners through ninth-graders in 18 states. To be eligible, students must qualify for free or reduced-priced lunch. When they start at Horizons, two-thirds of students are performing below grade level in math and literacy.

More than 25 local companies and nonprofits fund the Indianapolis program, which the Indianapolis-based education advocacy group The Mind Trust is citing as a model for what can be done statewide to reduce summer learning loss.

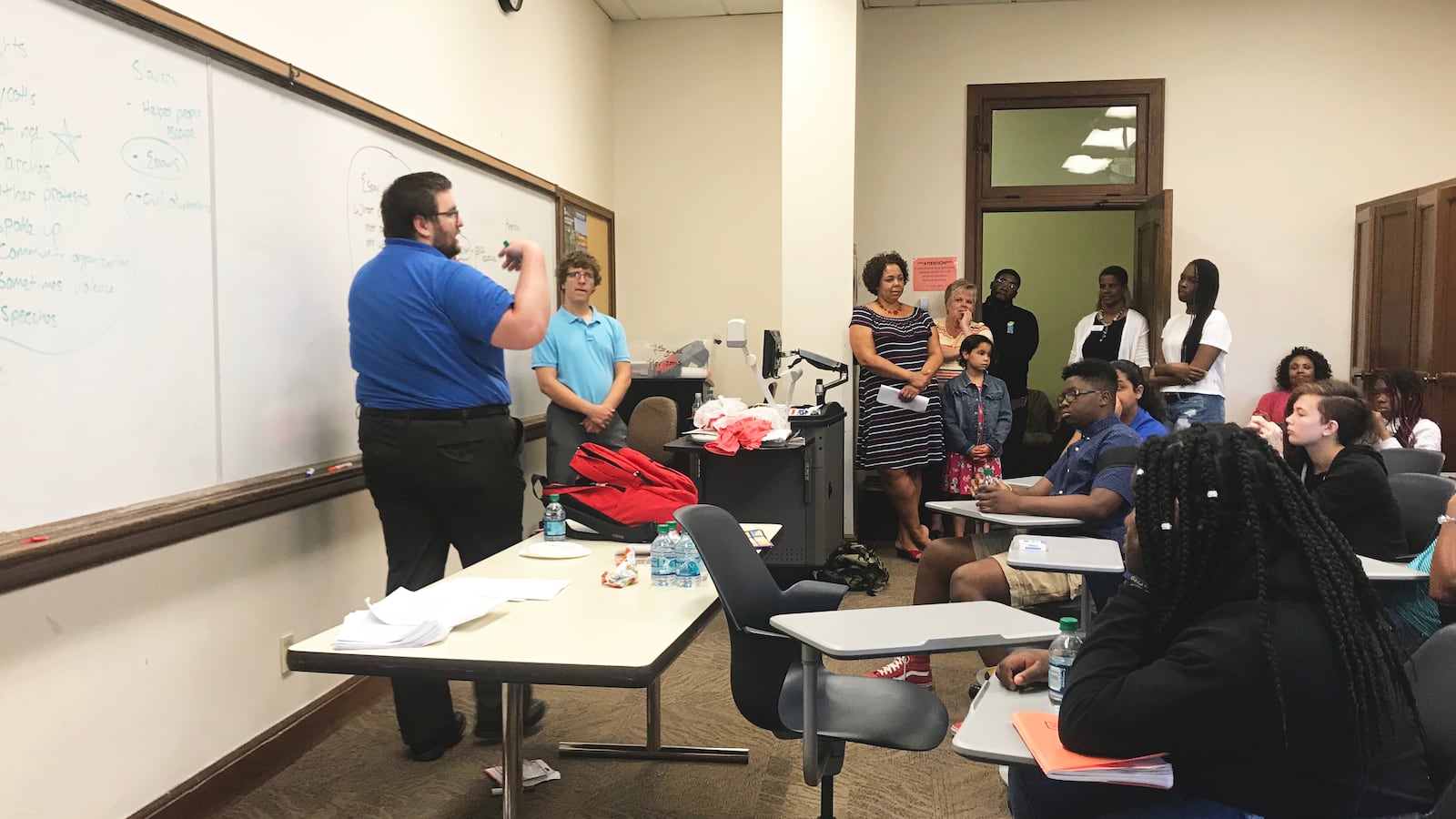

The Mind Trust, which regularly tours Indiana schools, summer programs, and adult high schools, organized a visit last week to a Horizons site at Butler University. Some 30 Indiana educators and community leaders came along to hear about Horizons’ approach to summer enrichment and to eradicating learning loss among its students.

“Oftentimes quality programs, not on purpose, can exclude the families who need it the most,” Marquisha Bridgeman, senior director of community engagement at The Mind Trust, told Chalkbeat. “Horizons is very intentional [about] making sure they reach families who are going to be best served by their program.”

Trinity, an aspiring doctor, told the visitors about her experience at Horizons.

During the summer program, each level is assigned a theme unique to their class, and study a novel based on that theme. This summer, such themes include “Plants and Nature,” “Building Healthy Communities,” and “Discovery through the Five Senses.” During the course of the summer, students are expected to complete independent projects related to that theme.

The eighth-grade theme, this year, is “A Force for Good.” Students are tasked with developing their own idea for a nonprofit organization. On field trips to the Children’s Museum and the Mid-North Food Pantry, they learn more about nonprofit operations.

The nonprofit Trinity wants to develop promotes gun control and gun safety. Later this summer, she’ll have an opportunity to present the group’s mission statement, volunteer plans, and budget to a panel of nonprofit professionals. The panel will assess which proposals are worth acting on.

“I hope my nonprofit is one of the ones they pick to actually consider trying to make,” Trinity said. “With the gun violence, I think I want to do one that keeps kids safe and that keeps them away from gun violence — even adults, too.”

Using the STAR assessment — a test used to assess student growth in areas such as math and literacy — Horizons found that its students show two- to three-month average gains in reading and math skills. That puts them four- to six-months ahead of where they have would otherwise been at the beginning of the next school year.

Horizons focuses on youth most at risk of falling behind.

A 2017 Children’s Defense Fund report found that 77 percent of Indiana’s eighth-grade students who qualify for free and reduced-priced lunch performed below grade level in reading, and 76 percent of these same children performed below grade level in math in 2015.

By contrast, 49 percent of students from higher-income families performed below grade level in both reading and math.

Teachers also use data from the STAR assessment, which students take at the beginning and end of the summer, to determine what areas students need the most help in. This helps shape classroom content.

Nick Stewart is the coordinator for Horizons’ site at Butler University, where middle school students spend their day. He said Horizons is focused on hands-on learning, which means more projects and fewer worksheets.

“You’re going to see students working to solve real-world problems with real-world solutions,” Stewart said. “They’re engaging content in a way that matters to them.”

Which makes the program popular with students and parents.

Although Trinity will age out of the program after this summer, she said she wants to come back as an intern when she’s in high school. “This is the place for me,” she said.

Like Trinity, 90 percent of last year’s Horizons students in Indianapolis returned this summer. There are nearly 100 families are on a waiting list.

“It’s great in one regard and sad in another regard,” said Shanna Martin, executive director of Horizons at St. Richard’s. “It’s helping us know there really is a lot of need out there as we think and plan for the future and other opportunities to expand and grow.”

To that end, the program will also serve Indianapolis Public Schools students during fall, winter, and spring breaks in the upcoming school year. Horizons will partner with Tabernacle Presbyterian Church to offer programming and meals at the church to students from nearby School 43, School 48, and School 60.