With an infectious smile, Pency Engmawii greeted 17 adult students Wednesday at the Excel Center-University Heights, a high school specifically designed for adults to obtain their high school diploma.

The gray chairs in the school’s English classroom are all occupied by eager students, and up until last year, Engmawii was one of them.

Engmawii, 28, graduated from the Excel Center in May 2017. Now, she’s back as an aide in her old class, and she’s using her own unique experience as a refugee from Myanmar, also known as Burma, to mentor and tutor other students who are new to the English language.

Engmawii’s journey to the Excel Center wasn’t easy, but with a high school diploma in her hand, she’s now on track to complete her degree at Ivy Tech Community College.

At 21 years old, Engmawii, the youngest of 12 children, left her small Burmese village in pursuit of education, something she said is unattainable in her home country.

Education in Myanmar can be hard to come by for poorer families, Engmawii said. Some schools must charge students a range of fees, including for textbooks and uniforms, making it difficult to afford.

“My family wanted a better life for me,” Engmawii told Chalkbeat.

After more than two years in Malaysia as a refugee, Engmawii was able to travel to the United States — alone. She came to Indianapolis because the city has one of the largest Burmese refugee populations in the United States.

About 14,000 Burmese-Chin refugees now live on the south side of the city, the IndyStar reported last year.

"My family wanted a better life for me."

Pency Engmawii

Engmawii said Indianapolis was promising since it provided an affordable place to settle with educational opportunities.

She learned about the Excel Center through her pastor, who was aware of Engmawii’s desire to learn. In 2012, she enrolled, a decision that changed her life.

Jessamon Jones was one of Engmawii’s first teachers at the Excel Center. Before becoming an education guide and mentor, Jones taught English to newcomers like Engmawii. In March, 44 percent of Excel Center-University Heights students were English language learners, up 20 percentage points from last year.

“It’s amazing because she was having those struggles of learning the English and taking the standardized tests and all that stuff you have to do to get the diploma,” Jones said. “She conquered that.”

Balancing a full-time job at a local Walmart warehouse with her courses at the Excel Center made it more challenging for Engmawii to find time to study English.

In addition to her English courses, which she retook multiple times in order to pass, Engmawii arranged times to meet with instructors outside of class. During this time, she would have basic conversations with teachers using the vocabulary she learned.

But Engmawii said learning English continues to be a challenge. She still spends hours each week practicing.

The language barrier even led her to change her career aspirations. Originally, Engmawii wanted to become a math teacher, but because she is not extremely fluent in English, she said she discovered another passion — accounting. She is currently pursuing a degree in accounting at Ivy Tech.

“I speak English, but it’s not very well,” Engmawii said. “So I am decided about accounting, it is better to me.”

But Holly Hathaway Thompson, Engmawii’s English 2 teacher, said she still hopes to see Engmawii come back to the Excel Center and lead a classroom in the future.

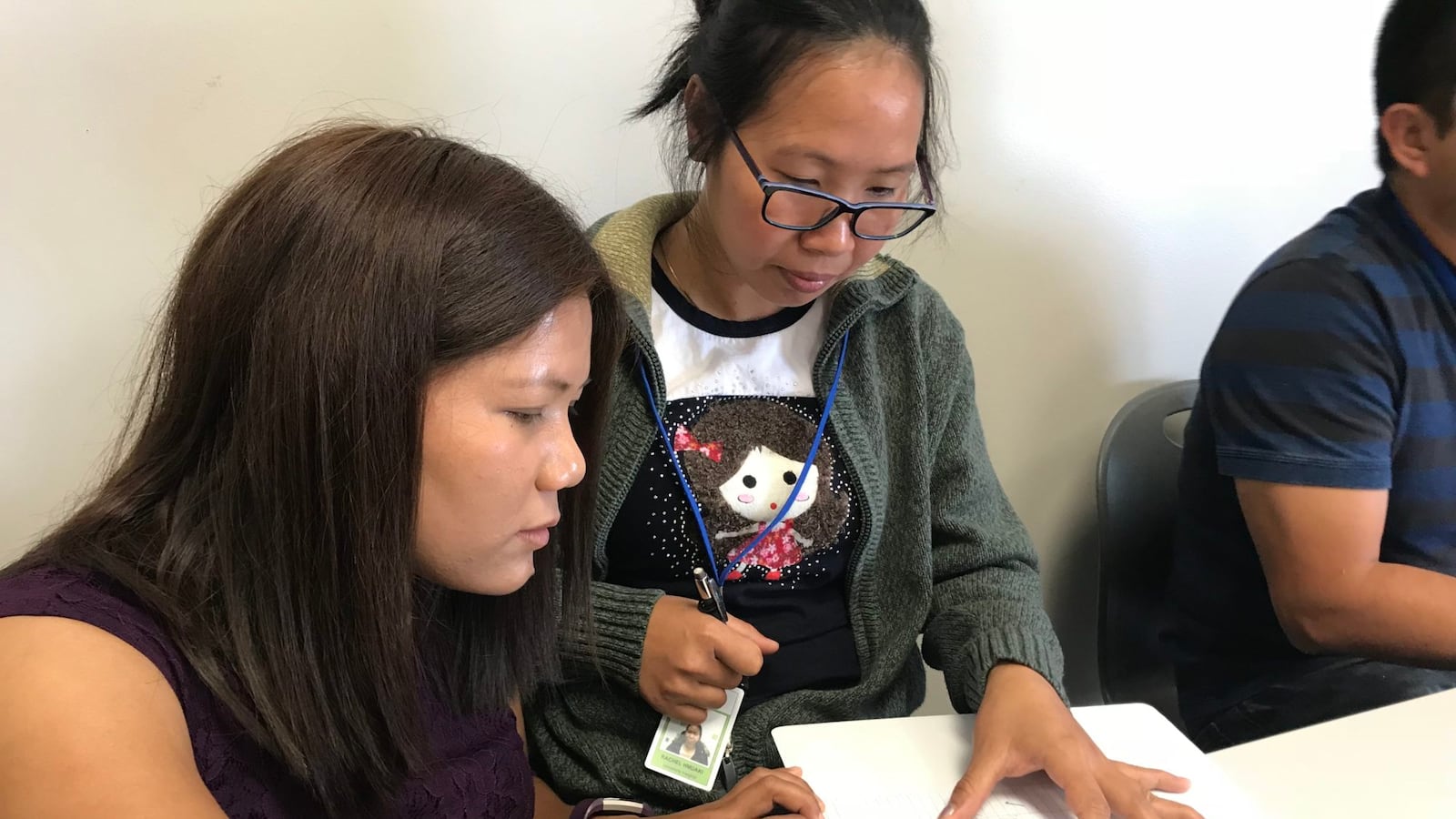

Engmawii serves as an aide in Thompson’s classroom on Wednesdays, helping other English language learners understand the curriculum. She also uses the class as a method of practicing her own English.

“I could see her being a teacher very, very well,” Thompson said. “She’s very good at making connections with [other students] and helping them feel safe and know that they’re not stupid. I think some English language learners feel stupid, and they’re not.”

On this particular Wednesday, Engmawii is helping students understand R.A.C.E, or Restate, Answer, Cite, and Explain — a concept used to write essays over specified reading materials. Thompson assigns Engmawii one half of the classroom to revise their R.A.C.E. paragraphs and offer assistance where it’s needed.

When Thompson steps out of the classroom for a brief moment Wednesday morning, it’s left in the hands of Engmawii.

“How long you take to graduate?” asks Rosa, a new student in Thompson’s class.

“Five years,” Engmawii responds with a sense of pride in her voice. She accomplished something that seemed impossible just six years earlier.

And in that moment, Rosa’s face shines with what looked like a glimmer of hope for her own future.