On the second-to-last day of school, kindergartners at Stout Field Elementary School on the westside of Indianapolis lined up to get a taste of first grade.

They walked down the hall, holding folders that would tell their new teachers how well they could read and where they were still struggling.

When the students started kindergarten 180 days ago, not all of them knew their letters or could write their names. But now, some of them can read through picture books on their own, sounding out new, longer words. They created their own stories in class and learned to count, add, and subtract.

“Show them your best work,” kindergarten teacher Mandy Sequin told her students before sending them to meet their first-grade teachers. “Make me proud. We’ve worked super duper hard.”

Children in Indiana don’t have to go to kindergarten, but it appears from school enrollment data that practically all of them do. With a new focus on preschool, and an emphasis on meeting higher standards in later grades, educators say kindergarten is becoming more rigorous — and a more critical building block for everything students will learn in years to come.

“To think about all that we learned in a year — they’re not ready if they come in at first grade,” Sequin said. “There’s just no way.”

It’s only been in recent years that the state has placed more value on this early childhood experience, making full-day kindergarten available for free to all Indiana families in 2012 and providing more funding for schools to offer programs — changes that education leaders predicted at the time would drive up kindergarten attendance.

Still, while most states require children to attend school at age 5 or 6, Indiana and a dozen other states wait until age 7. From time to time, educators and policymakers raise the question of whether school should start earlier for little Hoosiers, but lawmakers have so far balked at taking that choice away from families, and some say they don’t see a need to mandate kindergarten when so many children already attend.

House education leader Bob Behning, R-Indianapolis, said it’s most important to focus on making sure struggling students have access to kindergarten. The state’s growing pre-K voucher program for low-income families, On My Way Pre-K, requires recipients to send their children to kindergarten.

“That was a good way of making sure those who are most vulnerable and most in need not only get the bump in a pre-K program, but will continue to get that push that kindergarten would provide for them, in terms of being ready for first grade,” Behning said.

At Stout Field in Wayne Township, 82% of students come from families with incomes low enough to qualify for free or reduced-price meals. Students from low-income families are more likely to start school behind their peers because they might have less exposure to literacy and other learning experiences. But preschool or kindergarten can be a critical intervention as children’s brains develop in their early years.

“It levels the playing field,” explained Arthur Hochman, a professor of elementary education at Butler University. “If you and I are running a race, and every time we run a race, I get to start a lap ahead of you — why would you continue racing me? There’s no hope for you. You’re starting off behind the curve.”

In kindergarten, children are starting to have some of their first learning experiences. Words are a foreign language. They have to build up their number sense — how much is 10?

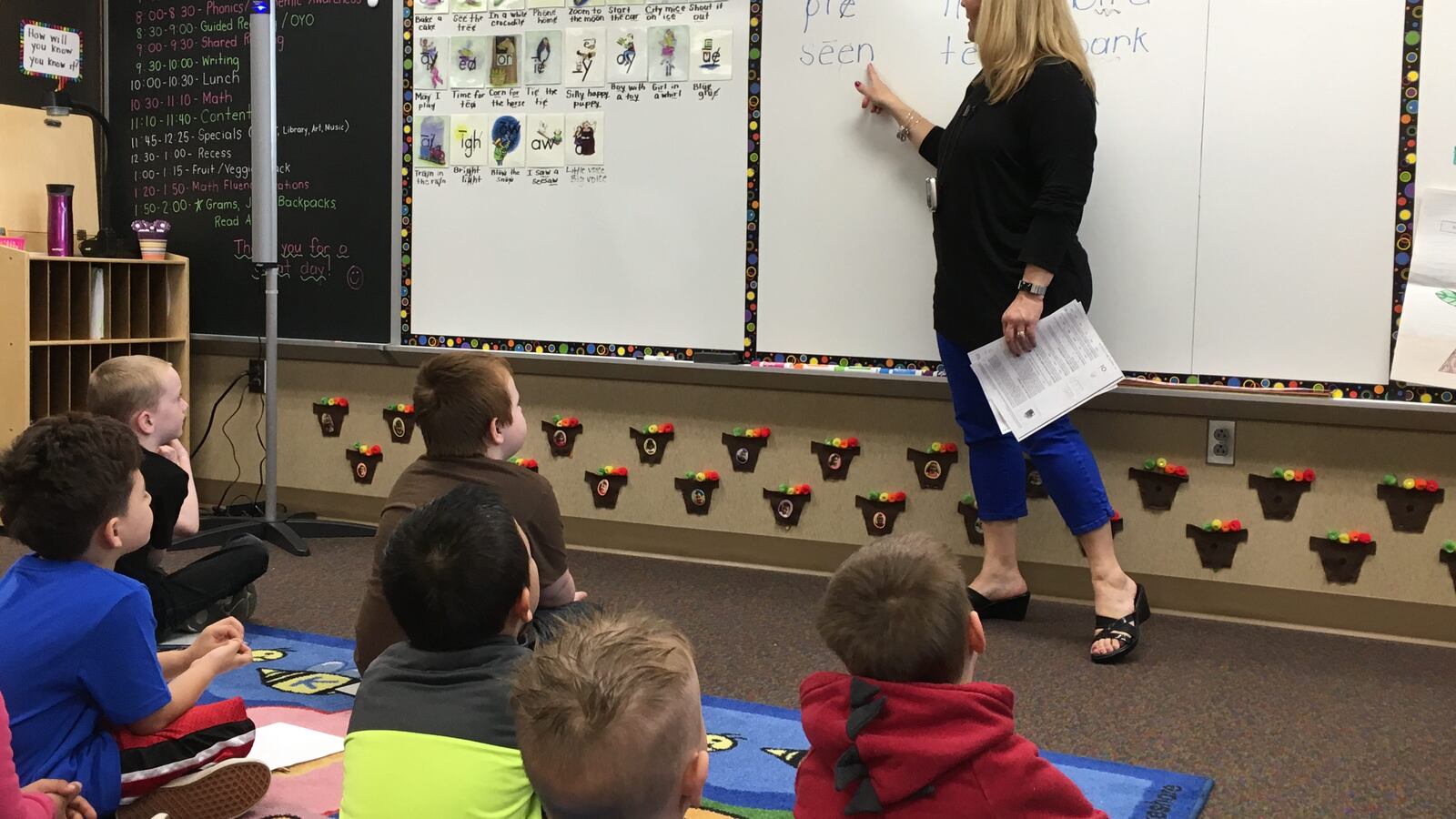

In Sequin’s class, the students count the number of days they’ve been in school with paper clips, making chains for every 10 days and a long chain for 100 days. To do subtraction problems, they draw circles and take some away by crossing them out, putting a big circle around what’s left over.

“Duh duh duh,” they practice the sound of the consonant “D,” and “puh puh puh” for P. They listen for words that have the same beginning sounds, or the same end sounds, or words that rhyme. They take apart words to change “join” to “coin” to “coil,” clap out syllables — “fi-nal-ly!” — and shout out sight words on giant flash cards: “she,” “you,” “who.”

Sequin had one student who never showed up for school, two who moved away, a few who joined partway through the year, and one who left for awhile but came back. Three students are learning English as a new language.

The children who struggle a little bit more tend to be the ones who weren’t here for the whole year, Sequin said. With less time, they don’t know the routines as well, so Sequin has to both help them and teach the other students how to be gentle with those who are behind.

“It rocks our world a little bit, when you’re in a flow,” she said.

Out of Sequin’s “family” of 17 students, all but one will be moving on to first grade. Some of them might have to work harder in first grade, but when Sequin looked at her class, she knew they would be ready. And it wasn’t just because they had studied consonant and vowel sounds, grouping numbers, and how plants grow.

A veteran teacher, Sequin saw how her 5- and 6-year-old students had matured. They could follow rules — or respond to a gentle reminder — exercise more self-control, and work independently.

By the end of the year, the students are ready to face their next challenges. Their first-grade teachers promise they will learn to love reading even more. The kindergartners sit at desks and marvel at the first-grade belongings stored inside. They get cups of crayons and a coloring page, and the teachers watch how they hold the crayons, what colors they choose, and how they share.

“Your picture has three words at the top,” first-grade teacher Samantha Kelly tells her future class.

One boy reads, “First… grade… ruh-ahh-kss… rocks!”

“You’re going to love first grade,” Kelly tells them.