In the weeks since Washington Township Schools closed because of the coronavirus, Michelle Offitt Allen has struggled to keep her two nephews on track with their schoolwork.

The boys — one in middle and one in high school — live with her 80-year-old mother, who was unable to keep up with the needed technology. Offitt Allen stepped in to field emails from their teachers and pick up a laptop the high school distributed.

She expected their days would look similar to a regular school day. Instead, she said they get assignments three days a week, which could take less than an hour a day to finish.

“Isn’t that weird?” Offitt Allen said. “Tuesday through Thursday. Then what are they going to think about Monday and Friday? Not much.”

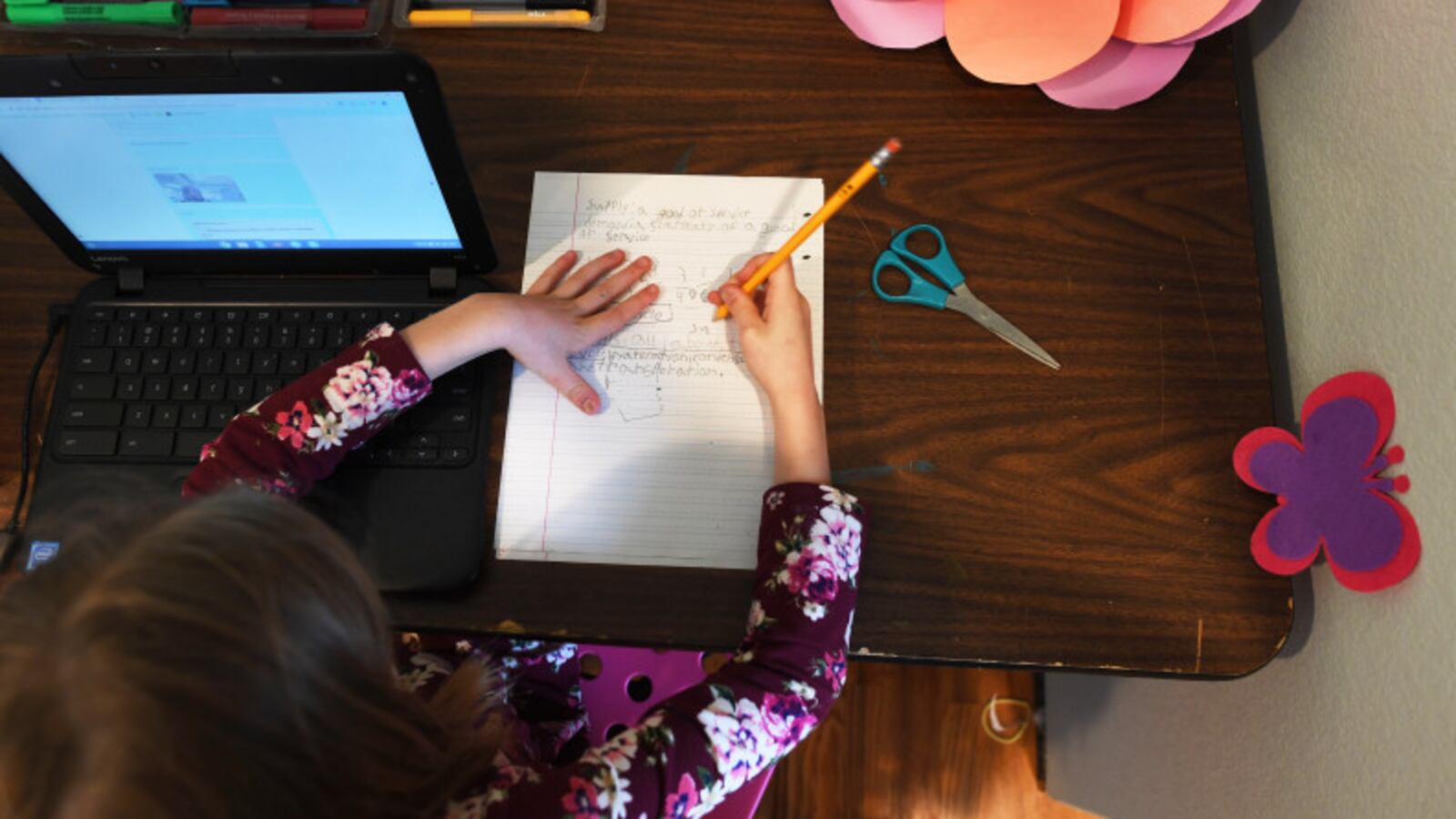

With the state’s Friday deadline for districts to submit their remote learning plans, Indiana is getting its first detailed look at what closures will mean for its 1.1 million students.

In Indiana, it’s up to school districts to decide how to meet the state’s mandate that learning continue remotely for the rest of the academic year. That means e-learning days look different as schools grapple with the best way to meet what are typically simple requirements — such as taking attendance and doling out grades.

The stakes are high because students will go months without classroom instruction, and those who don’t participate could fall further behind.

The Indiana Department of Education recommends that teachers give middle and high schoolers no more than three hours of work a day, with a minimum of half an hour of work for each subject. That time drops for younger students, to at least 90 minutes per day for grades 4 and 5 and about an hour for grades 2 and 3.

Angela Sheffield, a seventh-grade teacher in Lafayette, said those shorter hours take into account families’ varied schedules and make room for the discussions and group work that typically happens in the classroom. Most e-learning is distilled down to only assignments and practicing skills, she said.

“I think about how weary a student gets just doing those things, I think the timing matches that very well,” Sheffield said.

Many districts have opted to move to do three-day weeks to finish out the year, in part to give teachers time to reach out to students and prepare online lessons or paper packets. But how often assignments are posted and whether students are required to finish the work varies.

In many districts, students are left to work on assignments at their own pace. Some school systems have assignments due by the end of the day. Others, like Warren Township Schools, give students until the end of the week or longer. Deadlines for paper packets could be even farther out.

District leaders say it’s tricky to push students to participate and continue learning without punishing students who don’t have access to technology or who struggle without teacher supervision. That balance complicates both grading and taking attendance.

In Warren Township, Superintendent Tim Hanson said teachers are not giving out grades for K-8 students during closures, although teachers are still providing feedback on their work during biweekly video conferences or phone calls. High schoolers are still receiving grades on assignments, but the work they do remotely can only improve their overall class grade, Hanson said.

More important than grades, he said, is fostering human connections. “In this time where we are not able to connect, that is our priority,” he said.

The district scrambled this week to distribute around 7,500 devices that typically stay in classrooms to K-8 students after it became clear buildings would not reopen this school year. The district doesn’t have participation data, yet, Hanson said. Previously, when closures were thought to be temporary, students were given packets of optional work to do.

Students in Warren Township are marked present if they submit any work for the week or are in contact with a teacher, either during virtual class meetings or on one-on-one phone calls.

It’s a different approach than in suburban Avon Community Schools, where students are marked present only if they turn in their assignments posted online by teachers that day. At Tindley charter schools in Indianapolis, students must log on for video class meetings or risk being marked absent.

“We are sending a message that this is school but just school done in a different way,” Tindley’s CEO Brian Metcalf said.

Tindley distributed devices to students in grades 3-12 and helped families sign up for internet service. Attendance will not be used to penalize students, Metcalf said. Instead, the network plans to use the information to signal which families may need a check-in.

In Gary, schools started out by distributing paper packets to all of its more than 4,000 students, but has since moved to putting lessons online three times a week. Laptops were distributed to high school seniors, but other students are asked to use their own devices. The district is now down to delivering a few hundred paper packets, said its interim emergency manager Paige McNulty.

Only high schoolers are receiving grades, with teachers directed to be flexible. As for attendance, students are counted as present if a teacher is able to make contact with them at some point during the week.

“Because of the situation we are in where not all of our students have school-issued devices we don’t want to penalize students who don’t have that access,” said the district’s chief academic officer Kim Bradley.

Gary administrators said the district, using federal stimulus money, is considering moving up to the fall its plans to provide a device and hotspot for every student.

In the state’s largest district, Indianapolis Public Schools, elementary and middle school students are primarily doing paper packets of work, while high school students have virtual instruction. The district has not released an attendance policy yet.

Even in districts where students have a device and will continue to be graded, the content they are completing isn’t always as rigorous as it would have been in the classroom.

“I am not doing what I consider teaching,” said Sheffield, who moved to Lafayette Schools three years ago, but has been teaching for 27. “I am doing complete review work and keeping their minds active on reading or writing.”

Remote learning makes it difficult to gauge what a student knows and how many are keeping up, said Sheffield.

“I can’t build upon anything because I don’t have a sense of what the students are actually learning, if anything.”

As for Offitt Allen’s nephews, they are now doing closer to two or three hours of work each day as Washington Township continues to make its online learning more robust. When schools first closed Offitt Allen they were told none of their assignments would be graded, but then last week teachers sent emails saying some assignments would be graded after all.

That offers a little more motivation, Offitt Allen said. Until schools reopen, Offitt Allen said she’d like her nephews to do more each day, even if it’s not required schoolwork, such as reading a book or watching the news for half an hour.

“You’ve got to try to keep things as normal as possible,” she said. “So that you don’t get further behind.”