Three years after Indiana took over Gary Community Schools, the state now must decide if it will continue to shell out millions to the company running the cash-strapped and chronically low-performing district — giving families more to worry about than just how the coronavirus will affect school in the fall.

The state’s $6.2 million contract with Florida-based MGT Consulting comes to an end next month. The company is asking for another three years, saying that’s all it needs to get the northwest Indiana district out of takeover and stressing the importance of consistency.

The decision state officials make in the next few weeks will set an important precedent for how Indiana handles districts forced to turn control over to the state. While officials seem unlikely to make a drastic change at this point, they will also have the opportunity to set new expectations for district managers.

Since arriving in Gary in 2017, MGT has made deep cuts to stop the district’s chronic overspending and has reduced its $100 million debt, while receiving praise from state officials and pocketing $900,000 in state incentives along the way.

But some community members, fearing learning is taking a backseat to budget goals, are pointing to the benchmarks the company failed to meet. Those include improving the schools’ academic performance and increasing enrollment. MGT has appointed three different emergency managers to oversee the district in as many years and there continue to be reports of concerning conditions inside classrooms.

“There’s also an academic crisis that has been brought on,” Gary resident Tracy Coleman told state officials during a virtual meeting last week. Coleman is part of a parent group advocating for improvements to West Side Leadership Academy, the district’s only remaining high school.

‘The slowest to turn’

In 2019, five of the eight schools in Gary received an F rating from the state. Schools statewide saw low scores that year, the first year with the new ILEARN exam. But Gary’s passing percentage was among the lowest, with just 7.8%, passing both the math and English portions. And West Side’s graduation rate plummeted from almost 90% prior to takeover to 59% in 2019.

Improving academics remains a priority for the company, MGT Vice President Eric Parish said during his public pitch to the state last week. He attributed the drop in graduation rate in part to the fact that high schoolers switched guidance counselors each year and the school struggled to track where students went when they left, which may have resulted in them being marked as dropouts rather than transfers.

During the meeting, which was streamed online, district leaders said MGT plans to change how guidance counselors monitor high schoolers’ progress and create a dashboard for local testing data, so teachers can easily check where students are struggling.

Parish also pointed to some “building blocks” the emergency manager has put in place over the past three years, including new textbooks, monthly student assessments, professional development for teachers, and curriculum that aligns with state standards.

“I will be the first and last person to tell you the academic performance is not where we want it to be,” Parish said to state officials. “Two steps backward to take five steps forward. … We knew going into this that academics would be lagging. It’s the slowest to turn and it was a long time coming.”

But Parish has previously acknowledged in interviews with Chalkbeat that if the community wants to exit state takeover, finances — not buildings or academics — have to be the priority. State lawmakers wrote the takeover law so that a district can exit takeover without making academic improvements. All that’s required is posting at least two years of a balanced budget.

“The performance of the schools and the performance of the students was a matter of great concern,” said Luke Kenley, the since-retired Republican senator who co-authored the legislation. “But we didn’t feel like you could begin to address those without sorting out your finances.”

Rationing toilet paper

Stripping a school board of local control is a drastic step to take, with varied results nationwide. Earlier this year, the state returned control of four takeover schools back to their original districts, signaling waning enthusiasm in Indiana for state oversight of low-performing schools.

Lawmakers’ move to seize control of both Gary and Muncie school districts was a first for the state. Muncie was a C-rated district about an hour northeast of Indianapolis with mismanaged money from a school bond. The situation in Gary was more dire and complex, with decades of decline and red flags.

The once-booming steel city of Gary, located just 25 miles from downtown Chicago on the banks of Lake Michigan, has been plagued by challenges that come with de-industrialization and the loss of jobs — economic decline, population loss, increased poverty, crime, and neglect.

That, along with increasing competition from higher-performing neighboring districts and a growing number of charter schools, caused enrollment at Gary schools to plummet by more than half in the decade leading up to the takeover. There are now around 4,800 students.

In a state where funding is doled out per student, dropping enrollment meant fewer dollars. The district, which serves mostly black and low-income families, began struggling to live within its means, eventually racking up millions in debt to local vendors and taking out state loans to cover payroll.

When she arrived in 2017, former emergency manager Peggy Hinckley said there was no system for clocking in employees. Instead, their hours were tracked on paper by a secretary in each building. What computers they were using for finances were likely 20 years old, Hinckley said, which made it difficult for administrators to track where money was going.

Once she found a pile of brand new textbooks, still wrapped in plastic, gathering dust in a closed school while remaining classrooms were using books that were 10 years old. Many bathrooms didn’t have toilet paper. Teachers would keep a roll in their classroom, she said, and dole it out as students asked.

“Where in Indiana does a child need to get a ration of toilet paper to use the bathroom?” Hinckley asked. “I’ve been in 150 schools in Indiana, I’ve never seen that in my life. … It was a completely broken system.”

‘Nothing has changed’

Over the past three years, MGT has closed a school, outsourced services, renegotiated contracts, addressed fire code violations, and brought special education into compliance. Teachers, who hadn’t received a raise in nearly a decade, were given a stipend in December.

But community advocates say the company hasn’t made positive changes to the aspects of school that students experience, including its aging buildings.

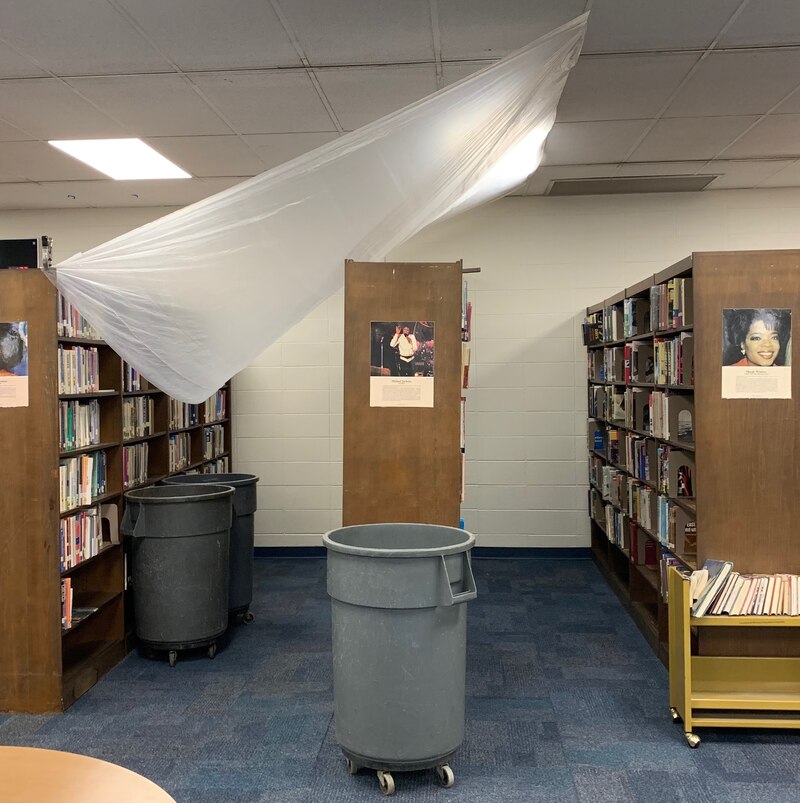

The district made headlines in October when a State Board of Education member revealed there were more than a dozen leaks in the ceiling of West Side’s library, and deteriorating buildings forced students to take classes in garage bays at the Gary Area Career Center.

“Nothing has changed,” District Advisory Board President Robert Buggs told the State Board of Education at the time, referring to school conditions. “There’s no reason in the world that a child should have to try to learn in an unsafe environment like that. Almost three years later and you see buckets everywhere.”

Last week, Parish said MGT plans to continue making improvements to school buildings. The district will have more money to do so after lawmakers passed legislation earlier this year allowing Gary for a little over four years to use its monthly loan payment to the state, about $500,000, for repairs and demolition. More than 30 abandoned schools sit empty around the city, some of which haven’t been used in decades and have created safety concerns.

Exit in sight

MGT will be able to balance the district’s budget — cutting another $6 million from its usual spending — by the 2021-22 school year, Parish said.

Part of his plan, however, includes increasing enrollment. Gary received around $7,530 in state funding per student in 2019. Using that figure, the district would need 160 new students to offset the funding loss expected when the county’s 10-year property tax cap exemption ends and the limits go into full effect for the first time.

Given the district’s current trajectory, that kind of enrollment jump seems unlikely. While enrollment dropped less drastically the last two years, it’s fallen by more than 300 students since takeover began.

And the coronavirus could lead to cuts in school funding statewide, as soaring unemployment causes income and sales tax revenues to plummet. That could mean losing money MGT was relying on to balance Gary schools’ budget.

It’s too soon to speculate how the coronavirus could impact MGT’s financial progress, said Justin McAdam, chairman of the Distressed Units Appeals Board, which is tasked with overseeing state takeovers. It’s still unclear how significant unexpected coronavirus-related expenses will be, or how much of those will be covered by federal aid.

Financially focused

The state has yet to consider other companies to run the troubled district. The board felt it was important to let MGT “present their vision and plan” before deciding whether to ask for other bids, McAdam said. Stability will be vital, he said.

In addition to the public virtual presentation, the board met with MGT to ask more questions during an executive session on Thursday. A public meeting will be scheduled for the vote on renewing MGT’s agreement.

Of the five voting members of the distressed units board, only one represents educators. Other members are either lawmakers or representing finance-minded entities, which could make it difficult for them to monitor academics.

When asked about the district’s declining test scores and graduation rate in February, McAdam, who is also the policy director for Indiana’s Office of Management & Budget, said the board understands academics need “significant improvement,” but that those results don’t typically happen quickly.

“The emergency management team has been working to implement nationally recognized processes for academic improvements and has brought in various groups and mentors to assist teachers and principals,” he said in an email.

A COVID-19 complication

But the coronavirus, and subsequent closure of school buildings, has thrown a big wrench into those plans. District leaders and teachers were forced to quickly adjust. Administrators are now working to move up to the fall plans to provide a device and hotspot for every student. It’s still unclear if school buildings will be allowed to reopen, so schools statewide are preparing to continue remote learning if needed.

At first, when the governor ordered schools to close, all of Gary’s students were doing schoolwork on paper packets. The district has since moved to putting lessons online three times a week. Laptops were distributed to high school seniors, but other students are asked to use their own devices. The district is now down to delivering a few hundred paper packets to students who don’t have devices or internet access, said its interim emergency manager Paige McNulty.

The situation could make it difficult to monitor whether Gary’s schools are improving academically. State standardized tests were canceled for 2020. And educators statewide have warned that missing weeks of in-person instruction will have a big impact on students’ performance.

How to handle school in the fall and how best to catch students up on what they’ve missed remain the most pressing decisions MGT will have to make, should the state renew their contract.

“Obviously [COVID-19] has created a significant disruption,” McAdam said during the virtual presentation last week. “It’s created a lot of uncertainty about where things are heading here over the summer and into next school year… This decision is probably not the highest decision on everyone’s list, so we want to make sure that we are thorough in our analysis and make sure that we hear from as many people as possible.”