When outrage over George Floyd’s killing by a white Minneapolis police officer and ongoing police brutality against black residents led to demonstrations across the country, it was natural for the ninth-grade boys in Kara Davis-Myers advisory to talk with her about it.

All year long, they had been discussing racism and its deadly toll on black men — a national conversation that has simmered throughout her students’ lives. The first semester, her composition class talked about Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black 17-year-old who was killed by George Zimmerman in Florida eight years ago. And they spoke of the football player Colin Kaepernick kneeling to protest police brutality and racial inequality.

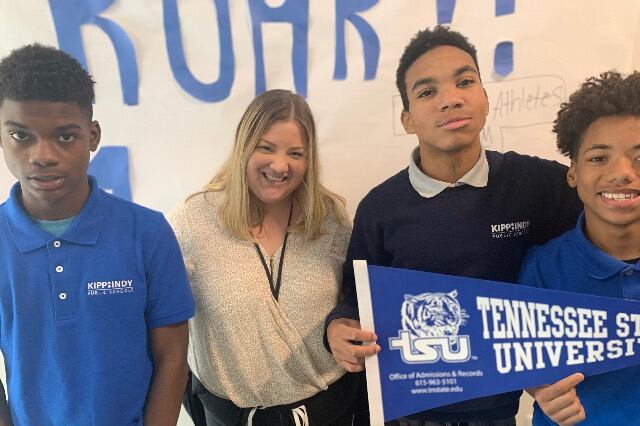

As a wave of rage consumed the country, students shared social media posts and chatted with Davis-Myers, who teaches at KIPP Indy Legacy High, where nearly all the students are black or brown.

As a white woman from the South, however, Davis-Myers believes that society needs to do more to encourage schools that teach predominantly white students to offer a fuller education in social justice.

“I just keep thinking about my hometown school and the private school I went to in seventh through ninth grade,” she said. “What can I do to reconnect, build relationships, and see what I can do about getting similar topics taught in schools of primarily white people?”

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

You typically talk about current events with your students. Are you discussing the death of George Floyd?

I teach composition. My class mainly focuses on citizenship and social issues that are going on in the world today. Before we closed school buildings due to the spread of COVID-19, we were focusing on a unit called social protests, where we were learning about police brutality and the protests that were engendered from the news of that brutality. So we were focusing on what were effective ways of protest and the kneeling of Colin Kaepernick.

We just had the last week of school. In the humanities department, for one of their final papers, students are writing letters to the mayor’s office about whether police officers should be required to wear body cameras. Some of the kids have put in the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd.

Are students more interested when you talk about current issues?

Yeah, absolutely. So much so that even outside of class, students will still be having these conversations. We did a unit on the opioid crisis and safe injection sites this year, and students were debating outside the class and talking to family members about it. There was a high level of engagement. They were able to see not only each other’s perspectives but the perspectives of their family.

When they get these real-life issues, they feel empowered, because they feel like they know how they fit into the world and how their voice matters.

Have you heard from parents, teachers, and students?

I have a group of about 10 boys that I check in with every day and I help get through work. We have a group message where we say, “good morning, let’s get up, these are things we have to do today.” Some of my students brought it into the group chat and were wondering if we had read about it. One of our students wrote about the George Floyd killing on Instagram. He wrote about the injustice of it: This is what we should do as a society to come together to acknowledge that this is happening and then find a solution.

How have you talked about it when students bring it up?

I have been listening mostly to a lot of their feelings and their thoughts and then encouraging them. I think that they feel comfortable talking about it with me too, because of the content that we learn about at school, and because of my class. I’m very honest with them about my situation. I was born in the South, and there are people in my family who are very biased and who are racist and who have a place of power and don’t recognize our privilege.

It’s been a reflection process for me as well. Yes, I can teach my students these things. And yes, I can have the curriculum in front of them, but I also need to use my privilege and my voice to talk and to share with white people the injustice that is happening and change other people’s minds about it. So I’ve been really open and honest with my students about that as well.

What does it mean to use your privilege?

My curriculum focuses on social justice and oppression, and I want to know what I can do to make sure these topics are being taught in primarily white or more privileged schools. Are these issues, facts, and data being brought up in white schools?

My students, they get it. They know. It’s very important for them to be agents of change. But it’s also very important for people who are in places of power to know about it as well. It’s not going to change if the misunderstanding of what privilege and racism are keeps widening.

How has it changed these difficult conversations when you are not seeing students?

This sounds contrary, but I think being in this weird space that no one has experienced before has made parents share more vulnerability with teachers, and teachers more vulnerability with parents and students. I feel more connected to their lives and what’s going on daily. Their parents will FaceTime me. So it’s almost more natural to have the conversation now.